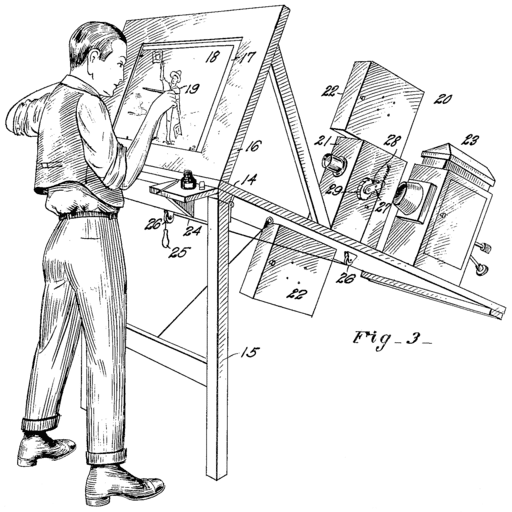

A century ago, Max and Dave Fleischer, two brothers from Brooklyn, developed a device that allowed animators to capture live-action events frame by frame. They tested their system on the roof of Max’s apartment building, where Dave, wearing a black clown suit, cavorted in front of a white sheet. Max captured the movements on film and projected them onto a glass plate that he then used to trace out pictures of individual movements. The result was rotoscoping, an animation technique that Max patented in 1915 that produced amazingly life-like movements.

Seventy years later, Jordan Mechner, another New Yorker, used this same animation technique to revolutionize computer graphics when he filmed his brother running, jumping, and climbing and then used rotoscoping to produce lifelike movement in video games.

Jordan began his pioneering work while still an undergraduate at Yale University. Dissatisfied with the stilted movement of characters in computer games, Jordan borrowed the technique of rotoscoping that he had learned about in his history of cinema class. In 1983 he began experimenting by filming his karate instructor, Dennis, doing a variety of martial arts moves. Then he traced images from the film and used a Versawriter graphics digitizer tablet to copy the images onto the computer. On March 19, 1983, Jordan finished a test of this to see if it would work in a game he was developing, and in his diary he recorded his excitement: “When I saw that sketch little figure walk across the screen, looking just like Dennis, all I could say was “ALL RIGHT!”” Jordan’s game Karateka (1985), a Japanese-themed karate game, became the best-selling title in the country and Jordan had established himself as a video game designer even before he had graduated!

After college, Jordan began work on what would become one of the great games of all time, Prince of Persia. For this Arabian fantasy of a hero who rescues the princess from the evil clutches of the sinister Grand Vizier Jaffar, Jordan sought to create even more lifelike actions by perfecting the rotoscoping techniques he had used to make Karateka. The materials he has donated to The Strong document how he went about doing this.

First, he videotaped his younger brother, clothed all in white, running, jumping, and climbing.

Then he took prints of individual frames and highlighted the body shapes so they would be easier to trace and digitize.

Once computerized, he combined these individual frames to produce lifelike, fluid movement in Prince of Persia. A clip of the game (recorded on an Amiga as part of ICHEG’s video capture project) shows how well Jordan translated his brother’s movement from film into the game. It’s not surprising, that when Broderbund first published Prince of Persia in 1989 it too became the best-selling game in America.

Prince of Persia pushed computer animation to new levels of realism and sophistication, and we are honored that Jordan has chosen The Strong to preserve these materials for posterity. These records—which include videos, business records, correspondence, artwork, games, and much more—will provide scholars the resources to understand one of the great achievements in the history of computer games.