Time can be as regular as clockwork or supple as our shifting perceptions of it. Each year I note the winter solstice and hold onto the certainty that each day afterward is growing longer, minute by minute. As the days lengthen, I inevitably succumb to the seduction of the gardening catalogs that “like clockwork” begin to arrive in my mailbox. Though the ground remains buried beneath drifts of snow, these harbingers of spring fill my thoughts with images of lush greenery, exuberant blossoms, and succulent fruit. Memories of last season’s planting disappointments—bulbs that didn’t bloom, flowers that didn’t thrive, and tender tomato vines bitten by the frost—have faded, and I’m ready to imagine the gardens that this year might hold.

For the ancients, the coming of spring was closely linked to survival. For me it is almost purely an emotional bond. Gardening is a leisure activity no longer connected to necessity. I love the sight and promise of newly turned fields, the smell of freshly mown grass, the delicate beauty of an unfolding flower. The ornamental garden and the cult of the lawn bloomed in America in the mid-19th century. Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape designer of Central Park in New York City, was a leading figure in the movement for public parks and suburban landscaping, promoting homes set well back from the road with flawlessly manicured lawns facing the street. The development of the rotary lawnmower in the 1860s not only made it possible for middle-class homeowners to maintain their lawns, but neatly coincided with the rise of such popular leisure activities as croquet and lawn tennis.

For the ancients, the coming of spring was closely linked to survival. For me it is almost purely an emotional bond. Gardening is a leisure activity no longer connected to necessity. I love the sight and promise of newly turned fields, the smell of freshly mown grass, the delicate beauty of an unfolding flower. The ornamental garden and the cult of the lawn bloomed in America in the mid-19th century. Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape designer of Central Park in New York City, was a leading figure in the movement for public parks and suburban landscaping, promoting homes set well back from the road with flawlessly manicured lawns facing the street. The development of the rotary lawnmower in the 1860s not only made it possible for middle-class homeowners to maintain their lawns, but neatly coincided with the rise of such popular leisure activities as croquet and lawn tennis.

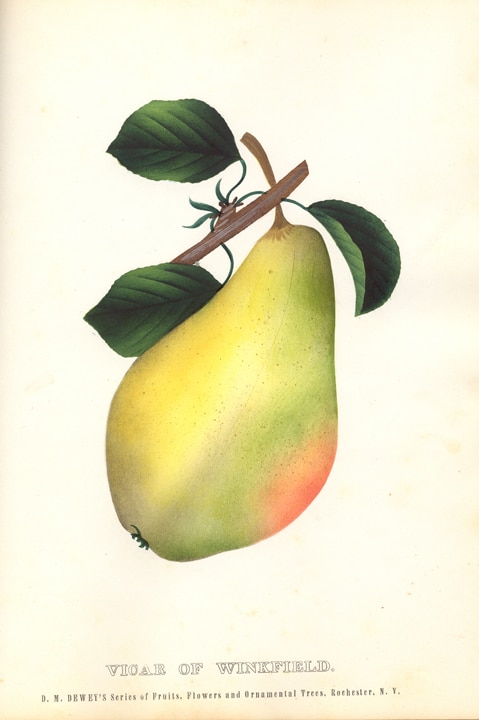

As enticing as today’s catalogs may be, they are a mere semblance of the fruit and floral illustrations that seduced gardeners in the mid- to late-1800s. The horticultural plates produced here in Rochester, New York, helped to establish Rochester as “the flower city.” D. M. Dewey, a local printer and publisher, was one of the first to recognize the marketing potential in publishing a series of high-quality “nurserymen’s plates.” These plates could be purchased individually or bound in sets to be used by traveling salesmen. So vivid are these plates that you can practically smell the flowers and taste the fruit.

As enticing as today’s catalogs may be, they are a mere semblance of the fruit and floral illustrations that seduced gardeners in the mid- to late-1800s. The horticultural plates produced here in Rochester, New York, helped to establish Rochester as “the flower city.” D. M. Dewey, a local printer and publisher, was one of the first to recognize the marketing potential in publishing a series of high-quality “nurserymen’s plates.” These plates could be purchased individually or bound in sets to be used by traveling salesmen. So vivid are these plates that you can practically smell the flowers and taste the fruit.

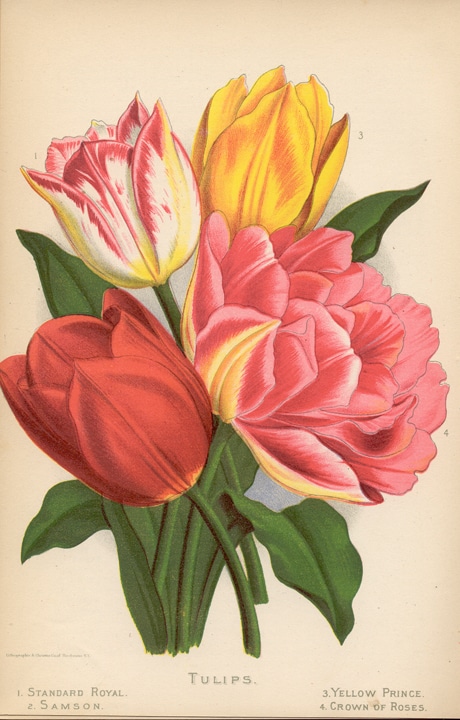

A Rochester contemporary of Dewey, James Vick was a devoted horticulturist, nurseryman, writer, printer, and publisher. In 1878, he introduced a magazine, Vick’s Illustrated Monthly, which featured a colored illustration each month. The quality and vibrancy of his colored prints are as appealing today as they were then.

A Rochester contemporary of Dewey, James Vick was a devoted horticulturist, nurseryman, writer, printer, and publisher. In 1878, he introduced a magazine, Vick’s Illustrated Monthly, which featured a colored illustration each month. The quality and vibrancy of his colored prints are as appealing today as they were then.

To achieve these naturalistic portraits, Dewey and Vick employed the separate techniques of the hand-colored lithograph and a stenciling process similar to theorem painting. In the first process, an artist created a drawing on a lithographic stone and then impressed it on paper. After that, an artist applied watercolors to create an image as close to nature as possible. With the second technique, an artist used a stencil used to create an outline on the paper. Then a production line of artists, mostly women and girls, each added one color. Finally, the artists applied a thin coat of varnish to stabilize the finished plate.

As the 19th century drew to a close, the advance of chromolithography and photomechanical techniques displaced these exquisite works of art. Less expensive and easier to mass-produce, these new processes were a boon to the nursery industry but a visceral loss to the garden enthusiast. Fortunately, the plates created by the early techniques have been preserved—including here at The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play—and are as bright and compelling as when they were first created. Between these beautiful illustrations from the past and the photo-filled catalogs from the present, I have plenty of inspiration for my gardening fantasies to tide me over until the first crocus appears—like clockwork.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.