Finally, an area where Millennials and Gen Z have an advantage: both generations have consistently had access to gaming on the go. From the Nintendo Game Boy to Tamagotchis to smartphones, if you needed to kill some time before meeting your friends (or wanted to ignore your siblings on a long car trip with the family), you could grab a portable gaming device from your backpack and voilà—instant entertainment. Our Gen X comrades remember when this wasn’t always the case. In fact, when the first electronic handheld games emerged in the late 1970s, these devices felt like the future.

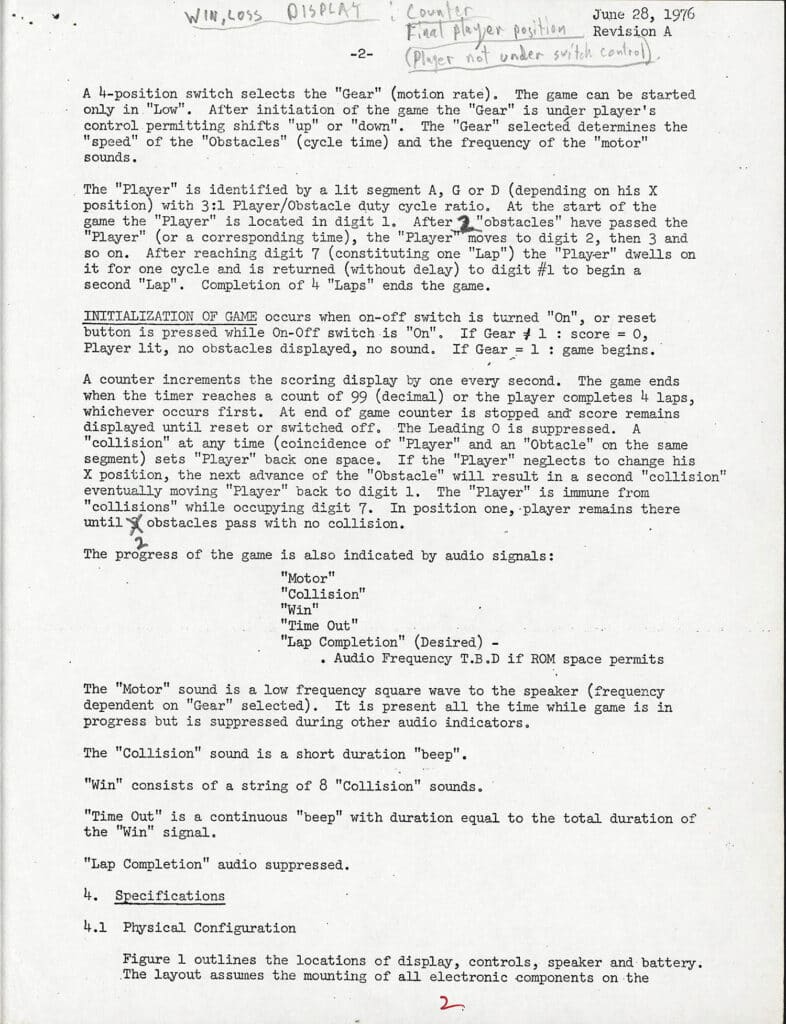

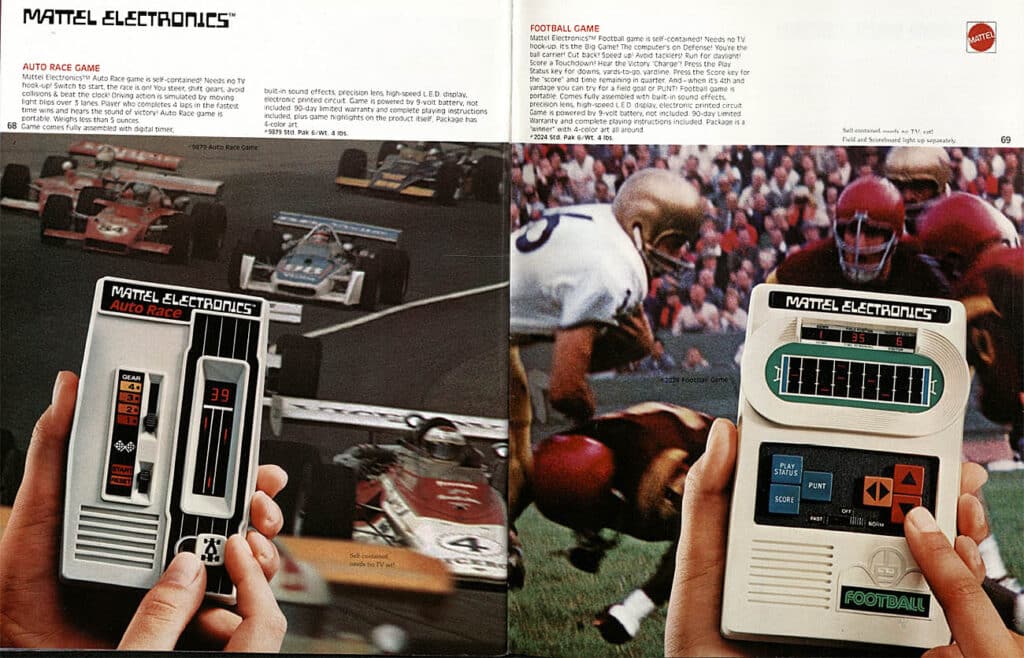

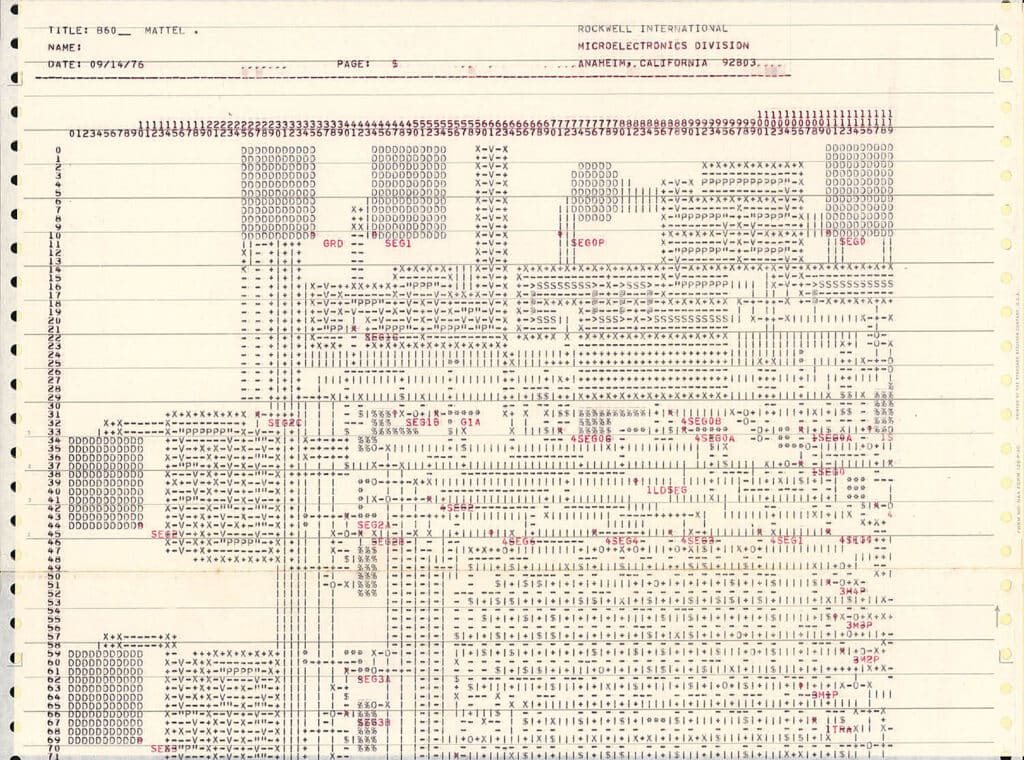

In 1976, Barbie’s parent company Mattel approached electronics manufacturer Rockwell International with an idea. Since electronic components (like the ones in powerful pocket calculators) were shrinking and video arcades’ popularity was skyrocketing, would it be possible to create a new type of plaything? Rockwell liked the idea and assigned young electrical engineer Mark Lesser to the project. Although Lesser had designed circuits for calculators, he had never programmed anything—but he quickly got up to speed. Inspired by his love for arcade games and pinball, Lesser spent months writing a program using punch cards on a minicomputer, eventually designing all of the game’s display, sound, logic, and scoring directly onto a 512-byte chip. (That’s about 1/2000th of 1 MB.) His first “obstacle avoidance” handheld electronic game resulted in Auto Race, a product which challenged players to navigate an LED “car” around opponents on a three-lane vertical racetrack. (This game is credited with being the first handheld game with only solid-state electronics.) Mattel executives were ecstatic.

Though Auto Race (1976) didn’t quite meet initial sales expectations, Lesser’s next game for Mattel proved far more popular than anyone anticipated. In 1977, they released Football and retailers couldn’t keep the game on the shelves for the next few years. The success of Football led directly to the creation of Mattel’s Electronic Games division, along with various competitor imitations. Lesser also worked on Mattel’s Baseball (1978) and Soccer (1978), cementing his importance in the video and electronic games industry.

The Brian Sutton-Smith Library & Archives of Play at The Strong houses the Mark B. Lesser papers, a compilation of technical documentation, notes, memos, and other information related to the programming of Mattel Electronics’ handheld games. Along with these professional papers, Lesser also donated several prototypes (including the one for Mattel’s Football!) and published video games to The Strong in 2019. The collection is a fascinating look at the technical side of game design. If your hardware can only hold so much memory, how can you efficiently program everything you need to run a game? (Also, the timeframe between Mattel’s initial inquiry and the production of Auto Race seems like such a quick turnaround, especially when you might expect a game project to take years to complete.) Lesser later went on to develop handheld and video games for Parker Brothers before forming his own company. He was subcontracted to program John Madden Football ’93 (1992) for the Sega Genesis before being directly hired to develop NHL ’94, one of the most popular sports games ever made.

Mattel’s Auto Race, Football, Baseball, and the titles that followed truly paved the way for portable electronic gaming. (In 2010, Time magazine even named Football one of its “All Time 100 Gadgets,” and the game was a finalist for the World Video Game Hall of Fame in 2021.) These days, we take for granted the accessibility to games on the go. But with a good idea and a little resourcefulness, Mark Lesser helped to ensure that handheld games would be playable for decades to come.