Game design is learned by doing. Get a game with a level editor or a scenario maker or whatever and create something. Get some friends to try it. Don’t TELL them how to play. Instead, watch them and see what happens.—Arnold Hendrick

Granting a rare interview in 2009 and reflecting on his career, Arnold Hendrick (1961–2020) described his passion for wargaming and then for game design. His first published game appeared as the game supplement in the wargaming magazine Strategy & Tactics in 1970. In that game, T-34, he attempted to blend traditional wargaming and its miniature figures with the complex rules and deep immersion of war board games—to produce a more accessible, simpler rule system that could be applied to many historical battle games. Hendrick’s design goal of blending approachability and engagement typified his game designs throughout his career. And both game designers and serious gamers remember and commend his works to this day.

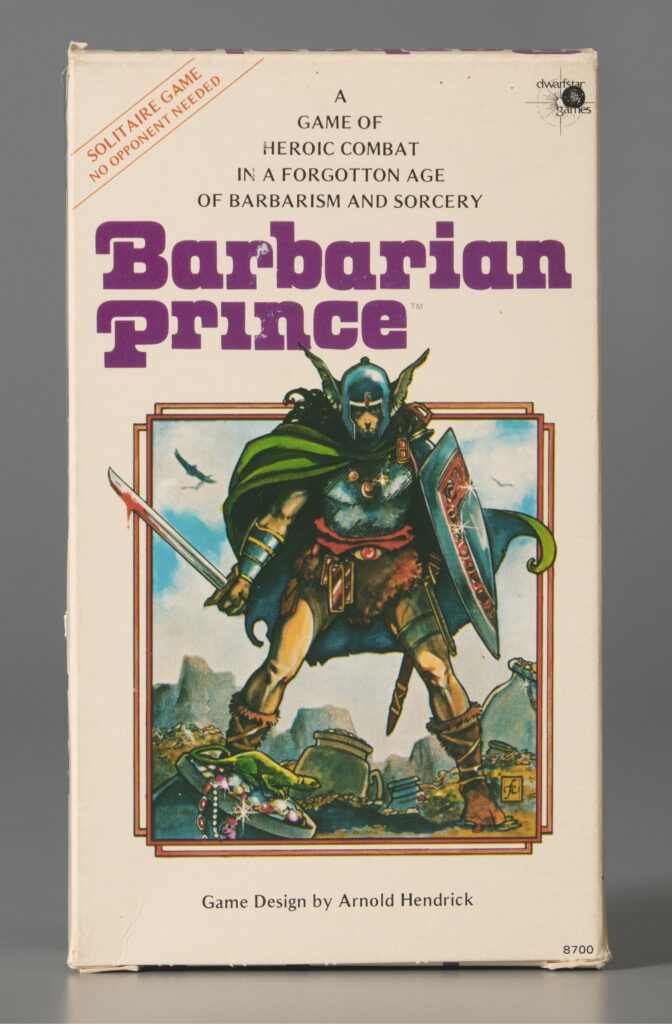

Hendrick embraced the 1974 creation of Dungeons & Dragons—the immersive fantasy game platform and world born of wargames—and soon afterward he “went wild” with the arrival of Traveler, a science fiction role-playing game (RPG) produced by Game Designers’ Workshop. Devising RPG systems of his own, he published one of his most successful games, Barbarian Prince, in 1981. Designed for solitaire play on an expansive scale, but packed in a small box, Barbarian Prince won the 1981 Charles S. Roberts Award for Best Fantasy Board Game. But 1981 was a boom year for video, or “computer” games.

My first experience in computer games was at Coleco as a “designer” (which there included Associate Producer work) starting in 1983. When Coleco imploded along with the rest of first-generation console gaming I joined MicroProse software and was there for ten years. —Arnold Hendrick

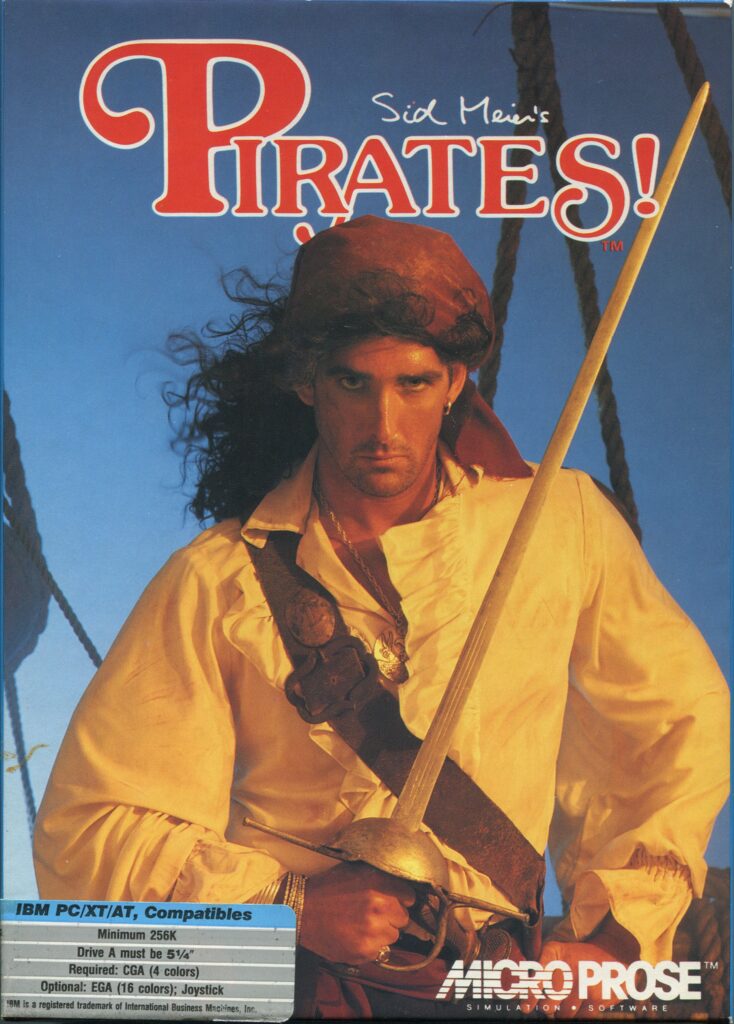

Hendrick deftly applied his war and RPG game experience to the burgeoning world of video games. The renowned game designer Sid Meier praised several of his innovations—they worked together at video game developer MicroProse. Meier admired how Hendrick brought his concept of permadeath—when a character dies, they cannot be played anymore—to video gaming; and Hendrick conveyed his knowledge of history to Meier’s game Pirates!—often cited as a groundbreaking open-world game. The two would ultimately go on to collaborate on 15 different games.

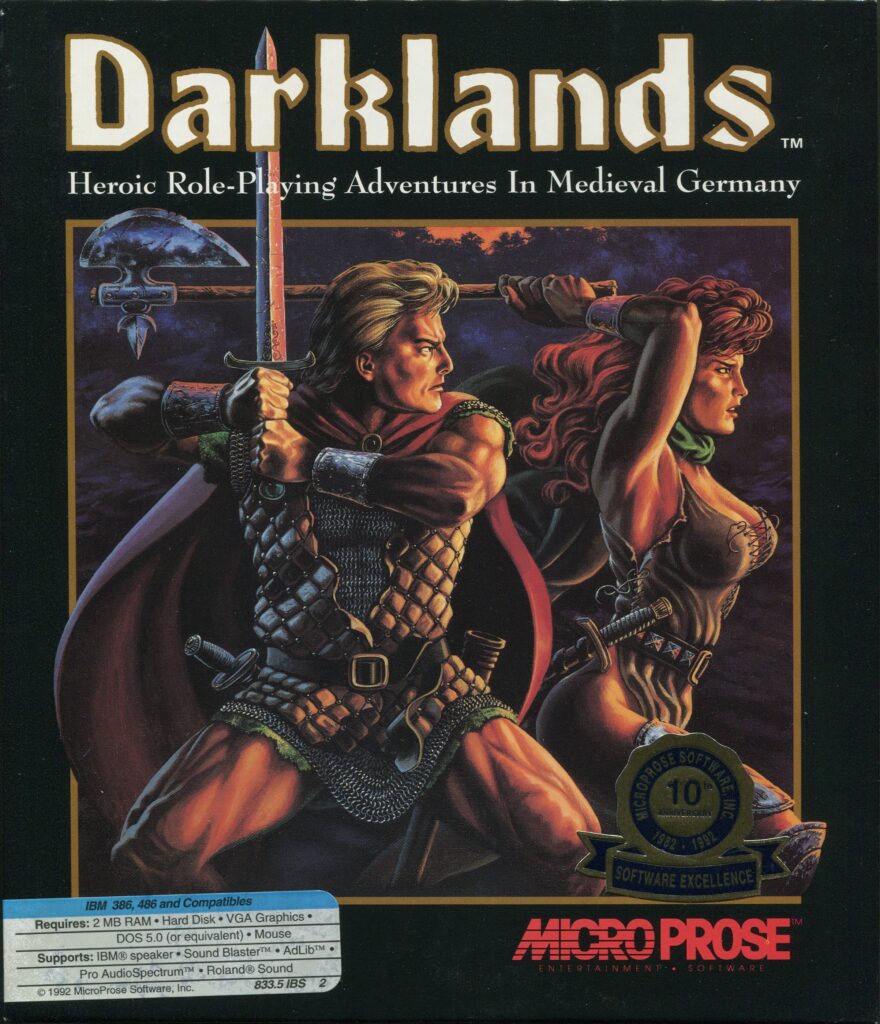

Hendrick served as the chief designer for MicroProse’s Darklands, a bold and innovative take on RPGs and open-world exploration released in 1992. Based on history, the game’s players adventure in a semi-fantasy world of saints and sorcerers. While players create teams, there are no levels, experiences, or statistics common to mainstream RPGs. Characters develop by progressing through skills, advance according to their occupations and ages, and eventually they die. Numerous game designers have since praised the game’s innovative mechanisms and rich immersion. Unfortunately, its release was plagued by bugs—much more of a problem then than in today’s world, where patches can be easily downloaded and repair a shaky launch. The game’s innovations, built from the ground up, while admittedly ahead of their time, brought its ultimate demise. But it remains well-loved by many devoted fans.

Hendrick’s contributions to traditional wargaming, role-playing table games, and video games during the time of their initial growth and development, comprise a part of the legacy he leaves behind. When game developers, his peers, heard of his passing, they mourned but they also often mentioned a design detail or an innovation he had made that they admired or that influenced them in some way.

I am deeply saddened by this. I was honored to work with Arnold in one of my first real game development jobs, on a number of games we did with Interactive Magic…. He was one of my first game development role models and taught me some of my first lessons in how to build and balance games. He is one of the first generation of professional game developers, and an absolute legend. His legacy is one of creating happiness. He will be missed.—Christopher Natsume