Opening the 1989 Sears Christmas catalog and perusing the fifteen-odd pages of video game advertisements, filled with pictures of boys and accented with blue, reveals what many women have felt for decades: games just aren’t made for us. Until the 1990s, video games were almost exclusively marketed to boys and men. Women, of course, can and did still play video games; but playing them meant wading through a swamp of sexist portrayals, if we were even lucky enough to encounter a female character in the first place.

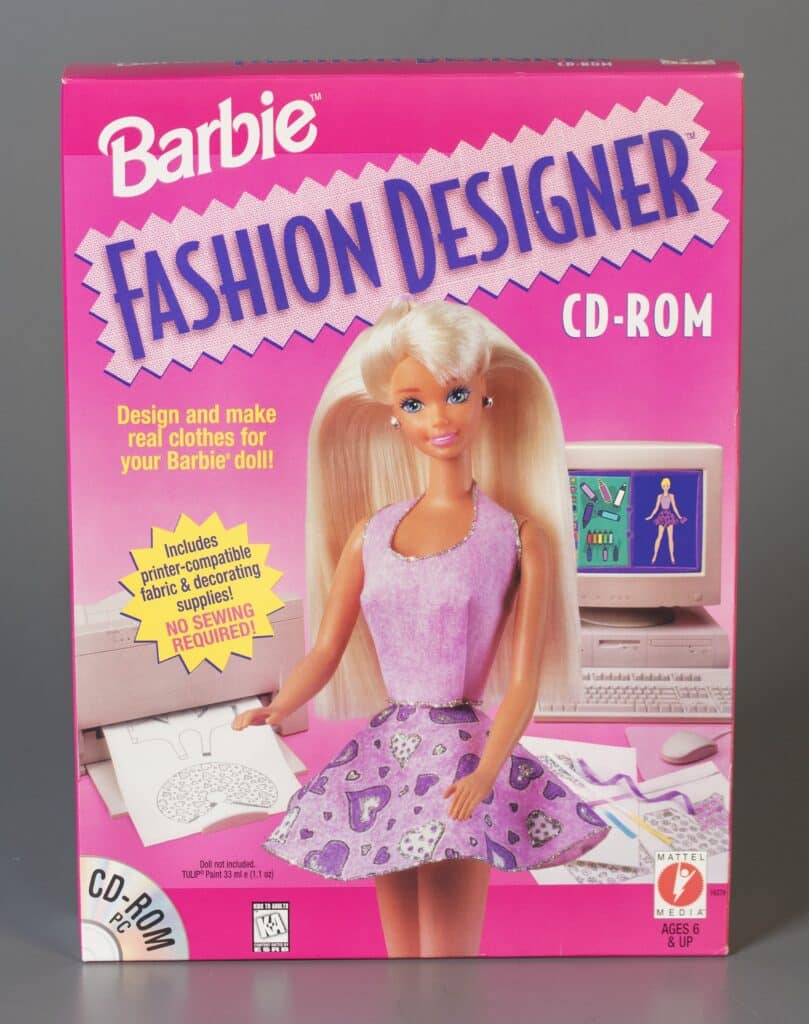

Then, in 1996, an unprecedented hot-pink box appeared in the software aisle: Barbie Fashion Designer. Unabashedly feminine, the game stuck out from its peers not only for its aesthetics, but for its dress-up gameplay. It was one of the first games designed specifically for girls. Barbie Fashion Designer was an instant sensation and commercial success for Mattel, and alongside Sega’s Cosmopolitan Virtual Makeover, these two games ushered in a new wave of games designed for girls. Game studios like Purple Moon responded to this burgeoning market by developing these “girl games,” characterized by gameplay involving dress-up and fashion, domesticity, dating, and shopping, all wrapped up in “pinkified” Barbie-inspired aesthetics.

Just as girl games became immediately popular, so too did they immediately generate controversies. Some feminists were concerned by the potentially sexist content of girl games, arguing that their gameplay perpetuated a narrow ideal of femininity centered around fashion, appearances, and relationships with men. Those on the other side of the debate claimed that playing girl games was actively participating in female culture and thus constituted an act of feminist resistance. In either case, girl games remain popular today, with recent titles like Infinity Nikki (2024) and Dress to Impress (2024) garnering millions of dedicated players. The last 30 years have proven that girl games (and the debates around them) are here to stay.

Most conversations about girl games place their emergence as a genre in the mid-90s with the release of Barbie Fashion Designer and Cosmopolitan Virtual Makeover. But digital games don’t just spring into existence—they are often rooted in an analog past. Girl games are no exception. As a longtime lover of girl games, I wanted to discover if there were any common threads between analog girl games and their video game descendants.

With The Strong’s generous support, I made the journey from Montana to New York to explore the museum’s vast collection of 19th– and 20th-century board games. My research goals were twofold. First, I hoped to contribute historical context for modern girl games and deepen our collective understanding of this significant, enduring genre. Second, as a game designer myself, I wanted to use my findings to offer informed suggestions to other designers working within the genre, so that we can continue to make girl games without perpetuating sexist ideals. My delightful weeks at the museum consisted of playing all manner of board games featuring women or girls. In addition, the knowledgeable staff at The Strong gave me the excellent suggestion of exploring the museum’s collection of trade catalogs, helping me uncover how these games were marketed during the period I was studying.

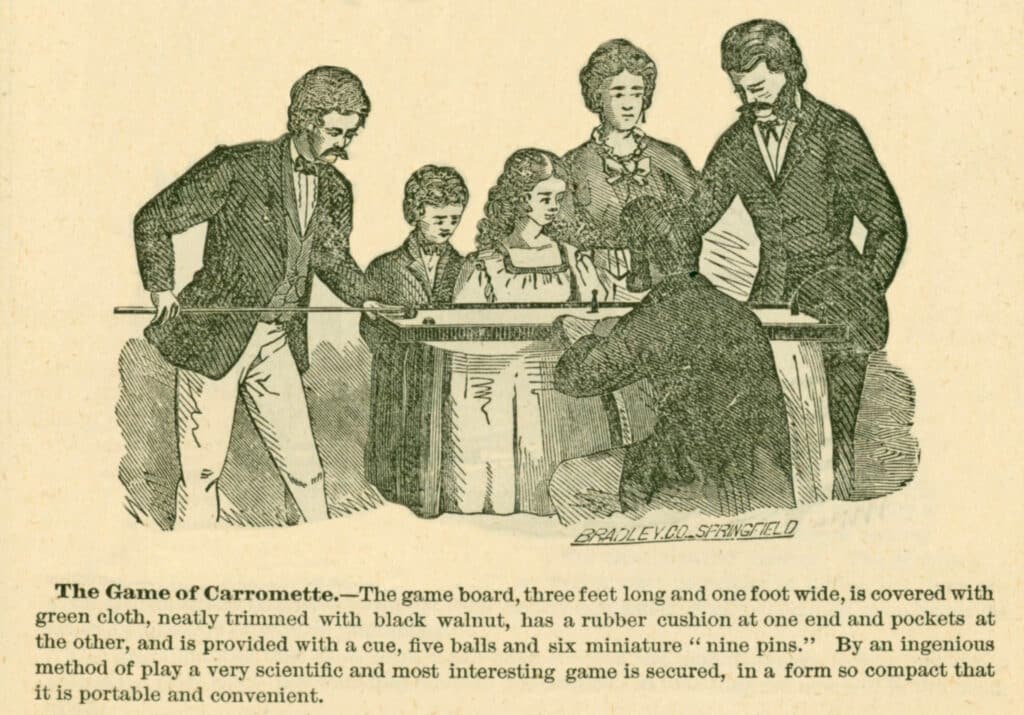

Before the 1960s, there were very few games that included depictions of women and girls; this was also true of men and boys. In fact, most games designed and sold from the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries were traditional—like Dominoes, Checkers, Crokinole, Parcheesi, and various card games—which tend to be abstract in nature. Far from being gendered, these games were touted as appealing to all ages and sexes. The 1873 Milton Bradley catalog, for example, depicts both men and women playing games in parlors. A Sears catalog from 1936 describes a Carrom board as offering “endless amusement for the whole family from little sister to grandfather.” For nearly a hundred years, traditional games dominated the market in America, purchased by middle-class families to play in parlors to entertain guests or pass the time.

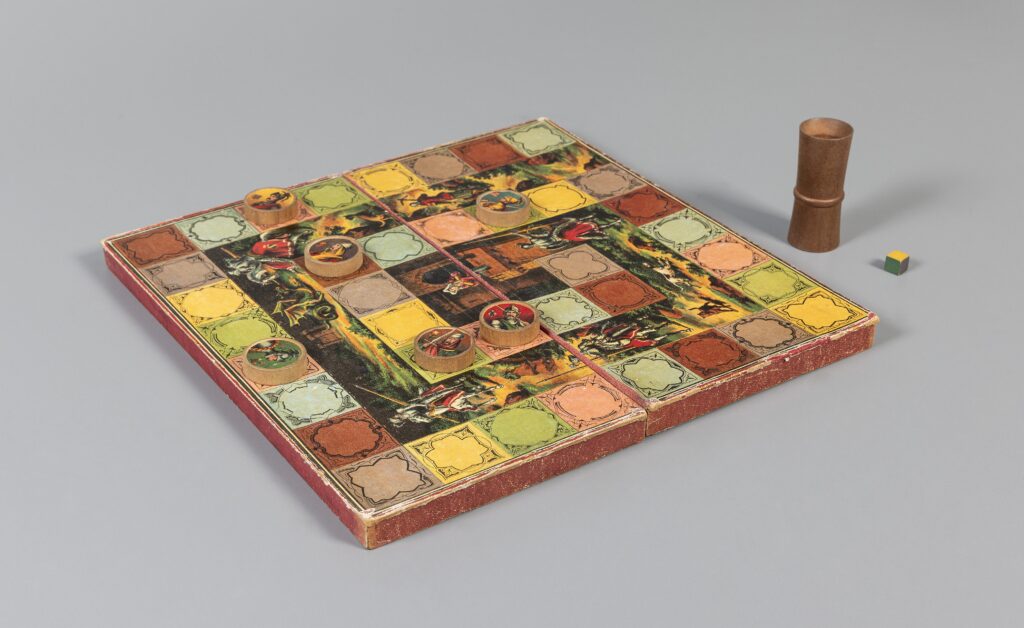

The few board games that did depict women during this era, like The Coquette and Her Suitors (1858), The Game of Captive Princess (1875), and Witzi Witch the Fortune Teller (1928) didn’t follow the conventions of the modern girl game genre. Notably, these board games don’t let you roleplay as women; rather, the woman serves as the player’s reward for winning. For example, both Coquette and Captive Princess feature male-only playing pieces, and players must race opponents to the finish line to win the maiden’s hand in marriage. This framing evokes the “damsel in distress” trope common to many early video games—but not girl games. Furthermore, the late 19th– and early 20th-century games I surveyed don’t feature the classic pink aesthetics typical of the girl game genre, nor do they include gameplay centered around fashion, beauty, or shopping. While most games featuring women from this period did include game mechanics and themes relating to marriage and courtship—a staple of modern girl games—the presentation of these themes and the lack of other important elements indicate that these early games don’t belong to the girl game genre.

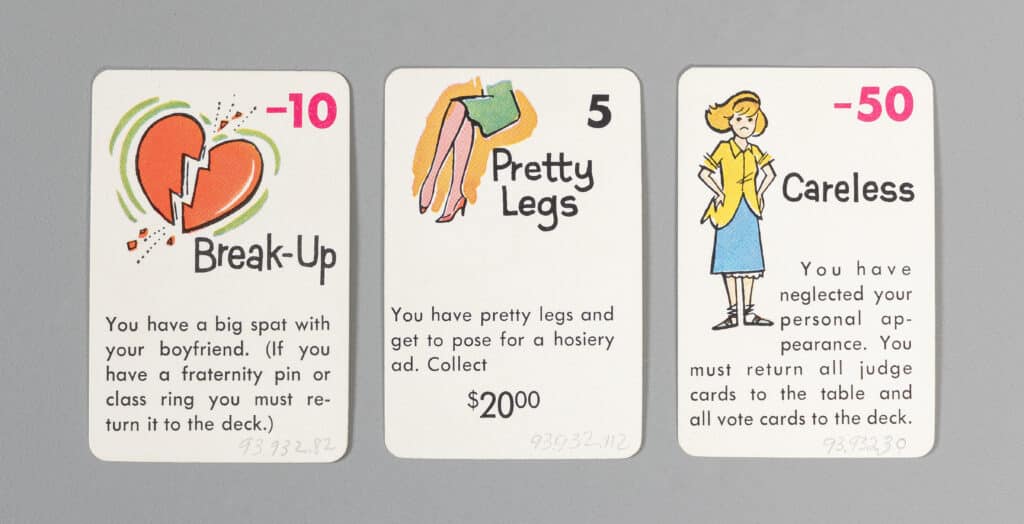

By the 1960s, however, the first obviously recognizable tabletop girl games entered the market. This marks an important shift in the history of analog girl games. While gender-neutral, family-oriented games were still designed and produced, games made specifically for girls appear now, advertised as “For Girls Only.” One example is Miss Popularity Game (1961) where girls compete against one another in a popularity contest to win a bright pink trophy; “The game that all girls love to play!” emblazons the box. The rules are straightforward: draw a card and see what happens. Cards like “Most Attractive Teen” and “Pretty Legs” score girls popularity points. Breaking up with their boyfriend (“Break Up”) and neglecting their personal appearance (“Careless”) loses them points. Drawing “Wardrobe!” and gaining a full closet awards 100 popularity points, the highest possible in the game. With a girly pink aesthetic, a strong focus on appearance and fashion, and themes related to dating and marriage, Miss Popularity Games serves as a quintessential “girl game” despite predating Barbie Fashion Designer by 35 years.

Miss Popularity Game is only one example among many. From 1960 to the mid-1990s, all board games branded as “For Girls Only” use the same pop-pink aesthetics characteristic of girl games today. Again, like modern girl games, half of these earlier board games contain themes or gameplay related to marriage and dating. For example, the entire premise of The Bride Game (1972) is planning the perfect wedding; in multiple others, getting a steady boyfriend is required to win the game. Most strikingly, every single board game analyzed from this 30-year period drew attention to the player’s appearance, discussing her wardrobe, body type, hair, makeup, and attractiveness.

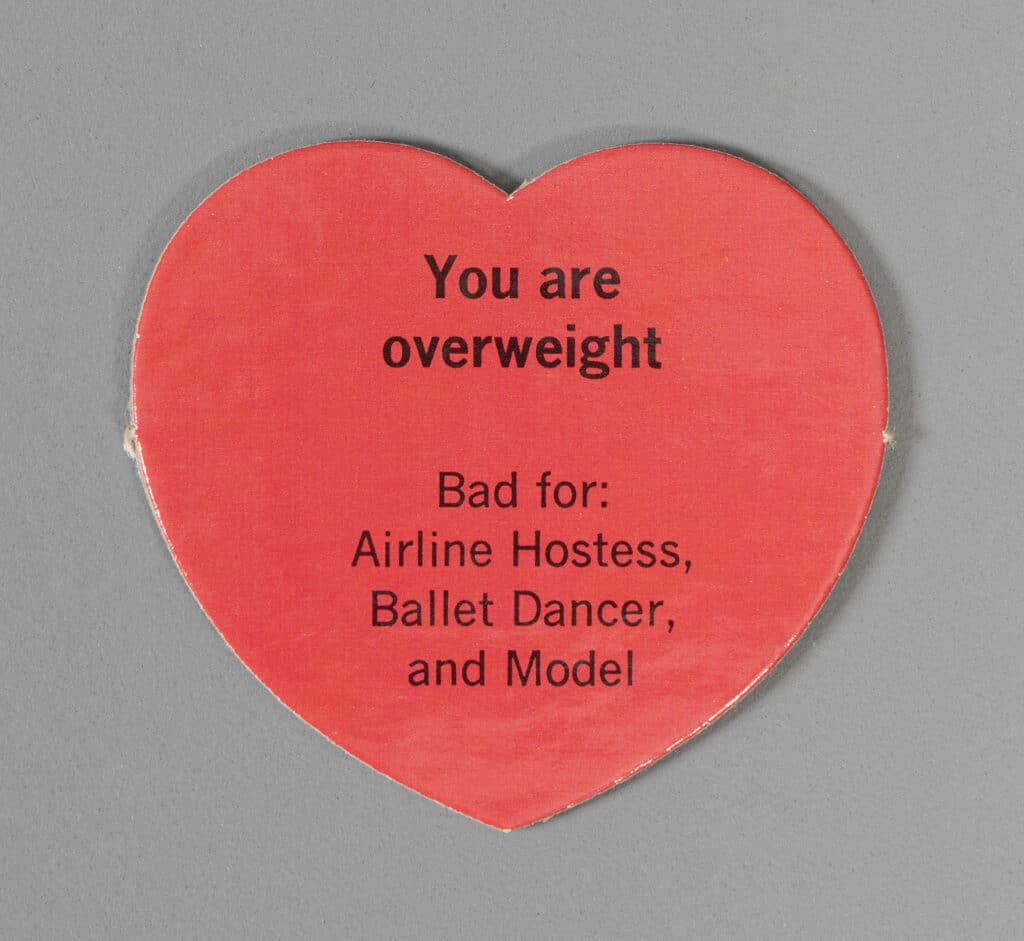

Focusing on the player’s appearance is necessary for dress-up and fashion games. However, many of these board games went a step further, punishing players for not being pretty enough, not doing their makeup well enough, or not being able to afford to go to the salon. In Girl Talk (1988), players must put a large red “zit sticker” on their face, intended to shame her if she fails. In What Shall I Be? The Exciting Game of Career Girls (1966; 1972), drawing a “personality card” describing the player as overweight means that she is unfit for pursuing a career as an airline hostess or ballet dancer. Many of these early girl games do present a narrow ideal of femininity, and girls learn they must be young, thin, white, attractive, and at least middle-class to “win.” This framing is tragic; no game designer should include mechanics that punish or shame players for failing to meet unrealistic beauty standards. No more zit stickers, please!

Of course, no genre of game is free from problematic titles. Despite the controversies, girl games tapped into experiences girls and women could relate to. Girl games established a new kind of engaging gameplay, which has maintained player interest for 75 years and counting. The aesthetics of girl games are eye-catching and vibrant; dressing up is a form of self-expression and engages the player’s creativity; relationships are important to our lives and negotiating them in game spaces is fun, allowing us to experiment safely. It’s not that we need to rid ourselves of girl games at all—in fact, I think we need more girl games, ones that broaden our understanding of what femininity is, and who it’s for. Rather than depicting femininity as something you can “win” and “lose,” girl games should give players a safe space to experiment with what gender means to them. Rather than being marketed only to girls, everyone should get the chance to dress up, play with romance, and wear whatever they want—including boys. I hope the girl games of the future invite everyone to play with femininity.

Written by, Ashley Rezvani, 2025 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow at The Strong National Museum of Play