As kids, we would sometimes say, as a mean joke, “He’s so dumb, he forgot how to play!” We thought it was funny then—as 10 year olds. But it’s hardly a laughing matter, then or now. The worry today comes with the knowledge that more and more kids aren’t learning how to appreciate free play—the type without rules or structure.

In the 1990s, researchers began to investigate Nature Deficit Disorder—the pattern of children becoming disconnected from the natural world by indoor play and supervised outdoor play—and to inform educators about related issues and concerns. Richard Louv’s 2005 book, Last Child in the Woods, opened eyes to the dangers inherent in the trend. I share the concern and alarm Louv expresses, and I couldn’t agree more with the conclusions reached in “Battling the Nature Deficit with Nature Play: An Interview with Richard Louv and Cheryl Charles” in the Fall 2011 issue of the American Journal of Play.

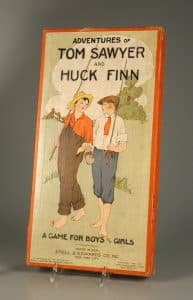

Coming from a time and a place where nature play was just about the only kind available, I know firsthand the value of outdoor free play. While I looked forward to visits from Cousin Joe, who always brought a new board game for us to play, I woke up most days itching to head outdoors to begin a new adventure. I was lucky to live in the country where free play was easy to come by, although if I told you some of the things my friends and I did in the name of play, you’d probably have a fit. As an adult now, I would agree with you too. Some of the things my friends and I did were nutty, risky, or downright mischievous, but all this free-play activity occurred within a mile or two of our homes. We were always—well, almost always—home by dinner time.

I managed to get myself into a number of fixes while outdoors and out of earshot. Each of those days began with free play, but usually ended with a free lesson. For instance, there was the time when I was eight or so that I got my feet stuck in the trapeze rings on our swing set. There I hung until my parents returned from a short errand. Of course, I never considered beforehand just how much muscle power it would take to extricate myself from my acrobatic position. I survived, chagrined but smarter—much smarter. And there was the time early one warm spring day when my friends and I built a dam in the creek. Excited by the large pool we created, we leapt in to see how it swam, forgetting just how cold the water was. We survived, chagrined but smarter—much smarter.

I managed to get myself into a number of fixes while outdoors and out of earshot. Each of those days began with free play, but usually ended with a free lesson. For instance, there was the time when I was eight or so that I got my feet stuck in the trapeze rings on our swing set. There I hung until my parents returned from a short errand. Of course, I never considered beforehand just how much muscle power it would take to extricate myself from my acrobatic position. I survived, chagrined but smarter—much smarter. And there was the time early one warm spring day when my friends and I built a dam in the creek. Excited by the large pool we created, we leapt in to see how it swam, forgetting just how cold the water was. We survived, chagrined but smarter—much smarter.

Another time, during a January thaw, a friend and I tried to walk across ice floes in a neighbor’s pond. Our combined mass tipped the ice, wetting the surface, and slid us helplessly into the murky, frigid water. We floundered to shore in our soggy woolens; chagrined and chilled, yes, but smarter—much smarter.

On yet another occasion, during a fishing excursion one hot summer day, I managed to accidentally hook my friend through his right eyelid as we walked along the road. Did I have pliers to cut the hook? Of course not. But I did get to watch the doctor give him a tetanus shot after Mom picked us up. Chagrined, yes, but now considerably smarter and much more respectful of fishing hooks.

On yet another occasion, during a fishing excursion one hot summer day, I managed to accidentally hook my friend through his right eyelid as we walked along the road. Did I have pliers to cut the hook? Of course not. But I did get to watch the doctor give him a tetanus shot after Mom picked us up. Chagrined, yes, but now considerably smarter and much more respectful of fishing hooks.

Not all free-play adventures ended this way, of course. There were a great many rather uneventful but well-spent days. Usually, I managed to come home unscathed, often with an interesting story to tell but always much wiser for the experience. Free play is essential to a free spirit. It allows us the experiences so necessary to face life’s issues head-on, to nurture our innate talents, to tackle problems with or without fear, to have faith in our decision-making ability, to develop our manual skills and, more often than not, to come out on top as a result. Those of us lucky enough to have gained valuable life experience this way—the occasional dunking in icy water or fish hook mishaps notwithstanding—don’t regret it for a second.

I fervently hope that the latest generations of kids have opportunities for their own outdoor free play experiences, and for the wisdom that they’ll each acquire. In my opinion, it’ll make them smarter—much smarter.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.