I had the amazing opportunity through a G. Rollie Adams Research Fellowship to visit The Strong National Museum of Play in order to conduct research for my project on metaplay.

The purpose of this fellowship was to build on my dissertation research, specifically delving further into the theory of metaplay. In my review of the literature, metaplay was poorly defined and inconsistent in its (under)utilization in scholarship since eminent anthropologist Gregory Bateson loosely introduced the idea in a conference paper in 1956 and renowned play scholar Brian Sutton-Smith vaguely alluded to it in The Ambiguity of Play (1997).

In my doctoral dissertation, I utilize a three-pronged approach to metaplay that draws on three additional theoretical components of play in order to examine and analyze contemporary digital game play practices. First is metagame or metagaming, which examines optimized forms of play or forms of play that deliberately take optimized strategies in mind, as put forward in recent articles by game studies scholar Scott Donaldson. The second is paratexts, in this context meaning any auxiliary or peripheral content surrounding a game or play. Examples include visual art, textual guides, industry-published guides, user-made content, and so on. The third component is capital, as discussed by the well-known sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (The Forms of Capital, 1986), but also particularly gaming capital, as put forth by distinguished game scholar Mia Consalvo (Cheating: Gaining Advantage in Video Games, 2007), that examines the authority or “credit” to players, content creators, developers, and publishers garner and can wield to influence the direction of play practices.

Although I focused on digital gaming, I argue this approach can be widely applied to play and interaction more generally. While maintaining confidence in my doctoral research, I wanted to see if there was anything further that I hadn’t already consulted. I was curious if previous research and scholarship, particularly from Bateson and Sutton-Smith, would reveal any secrets or possibly see if research had a metaplay lens, even if not specifically named.

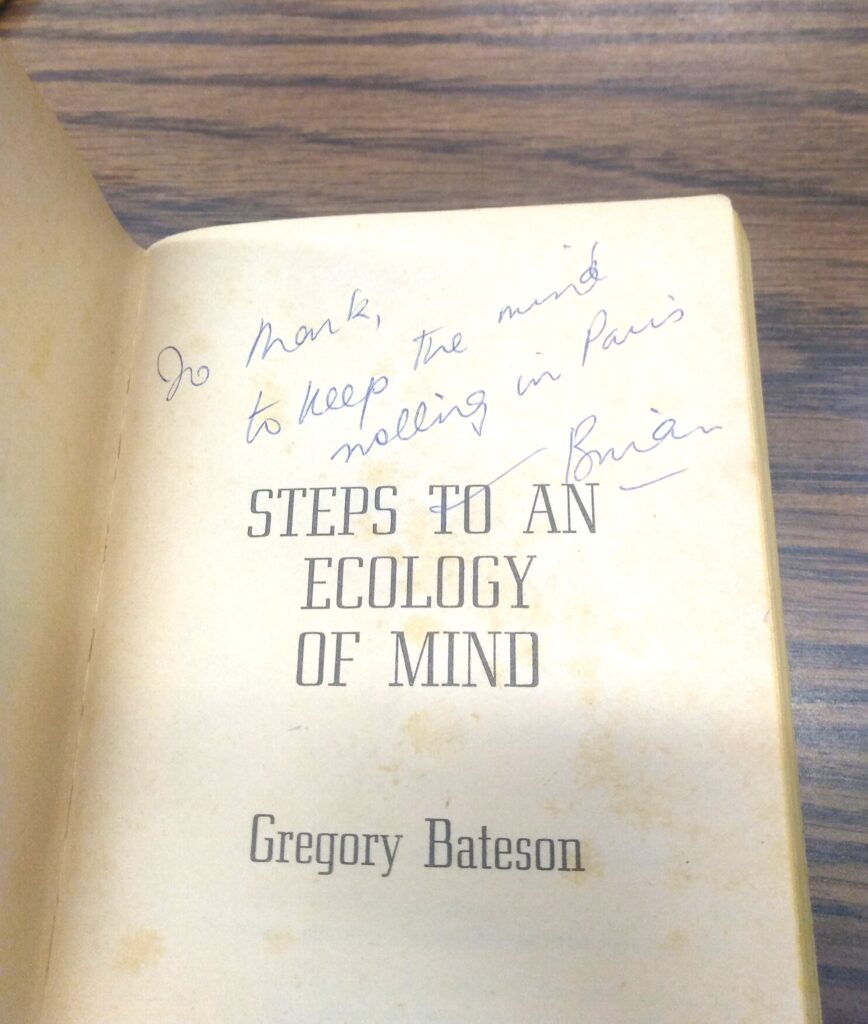

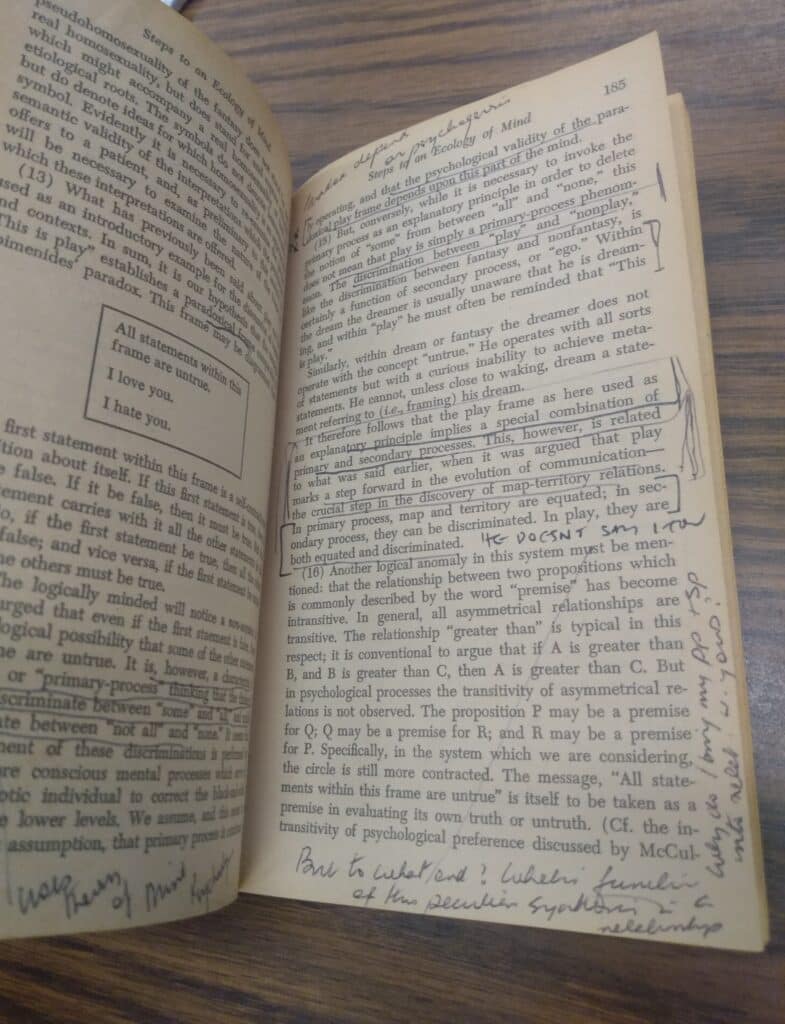

In the Ambiguity of Play, Sutton-Smith loosely refers to metaplay through discussing paradoxes of play found in meta-action and meta-communication, particularly in reference to Bateson’s 1956 paper “The message, ‘This is play.’” Bateson would proceed to build on this work in his Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972). Here, I had the extraordinary and unique opportunity to consult the very same copy Brian Sutton-Smith first read and made comments and notes in.

The same phrases Sutton-Smith uses in these notes in the 1970s would appear in The Ambiguity of Play 20 years later, particularly phrases pertaining to the paradox of play. This referencing of the paradox of play became more prominent in Sutton-Smith’s work after reading Bateson’s book. Seeing his notes in the margins and how influential this book would become to his thinking was a treat.

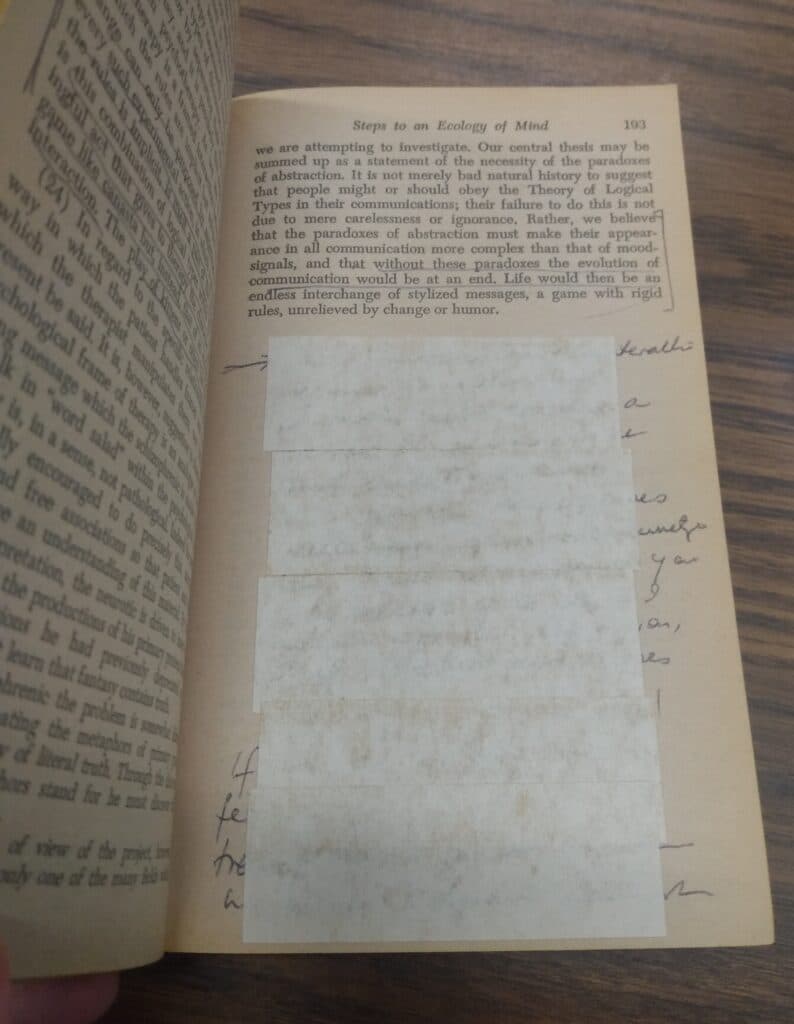

The most annotated paper in the book, “A Theory of Play and Fantasy,” would become a staple in the fields of play and game studies. The notes that Sutton-Smith made here would be informative for play scholars for years to come, though the paper did still lack a definitive answer to metaplay itself. I found myself especially intrigued by a series of notes Sutton-Smith wrote at the end of the chapter but that had been covered up.

I could not decipher what was written here, and it was not feasible or appropriate to remove the covering. Who made the patch? Was it Sutton-Smith or someone else? Was there an insight here or a misinterpretation? I continued on through the Sutton-Smith papers archive, and followed the citations found in different research and conference papers. In turn, that led me to many different kinds of theorizing on metacommunication, meta-actions, and metapragmatics from multiple authors. A considerable amount of research referenced Bateson’s paper, and metacommunication has been the subject of serious scholarly debate. Improvisation and pretend play research often skirted between blending metacommunication and metaplay, but only a handful of papers followed through on the side of metaplay with differing approaches (see classroom play research by Stuart Reifel & June Yeatman, research by childhood play scholar G.G. Fein, and early childhood scholar Jeffery Trawick-Smith).

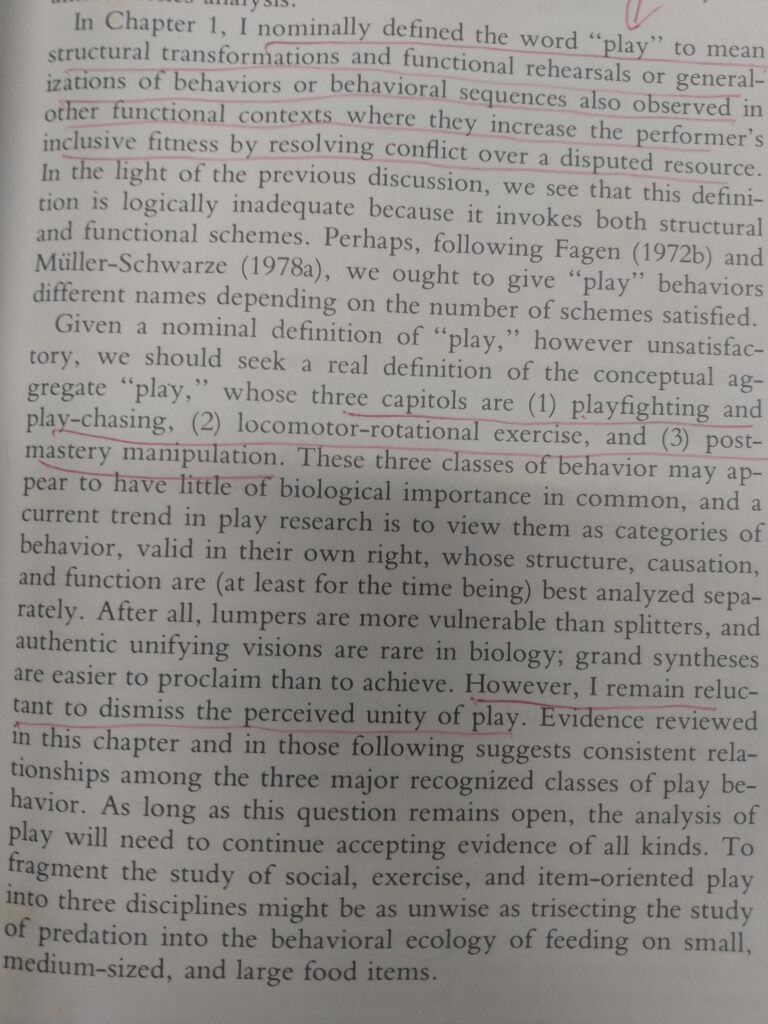

While reading different studies and takes on play, particularly those discussing communication or action in play, Robert Fagen’s Animal Play Behavior (1981) was often referenced. I am indebted to The Strong’s Dr. Jon-Paul Dyson for encouraging me to check this book, as I had not read Fagen’s work before. I was delighted to find Fagen put forward what he called an “aggregate” definition of play that also carried three components, so similar to my proposed definition of metaplay.

This was a highly important breakthrough for me, as it demonstrated the validity of proposing an aggregate definition that had multiple listed components. It also demonstrates, through research that references or draws on Fagen’s work, that utilizing part of the definition, or focusing on a particular component, does not invalidate the definition as a whole. Fagen stated that an element of vagueness remained, and through my own research I believe that vagueness is actually beneficial to play scholars. Similarly, I believe metaplay’s nebulous nature gives it strength to tie different play practices and phenomena across time and space. Throughout the different play studies I read while at The Strong, I could find trace elements to bring different pieces together to paint a broader picture of play.

One of the biggest strengths of the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and the Archives of Play was the ability to chain-link so many different studies and publications, no matter how small or slight. Being able to see a reference made to a particular article, conference paper, or book and then having access to that resource makes the archive truly invaluable. When I applied for a fellowship, I had a suspicion that I would quickly start branching out and going down rabbit holes outside of the list of resources I submitted, and naturally that did end up happening. Special thanks to David Sleasman and Stephanie Ball for entertaining my requests outside of my pre-arranged lists and for preparing the books and archival material for me. Coming from a background in Information Studies and Sociology, I had been unfamiliar with both Bateson and Sutton-Smith until I had started my qualifying exam studies. The Strong’s resources, including a variety of books with dedications, hand notes, and archived drafts and conference notes, demonstrated to me not only their importance in the field of play studies, but also the significance and impact they had on a number of scholars and their research.

In the end, I did not uncover a particular definition of metaplay that I found satisfactory. Bateson, Sutton-Smith, and others were content to let their description be nebulous and vague with room for interpretation. Older studies of children’s play mostly excluded external communications, instead focusing on direct communication as it happened in immediate play and play situations. R. Keith Sawyer came close in his book Pretend Play as Improvisation: Conversation in the Preschool Classroom (1997) but leaned more into metacommunication. This is understandable given the lack of telephones, smartphones, the internet, and instant communication platforms. The ability to continuously discuss, engage, consume, or interact with play or a game on a more fundamental level through these platforms has dramatically shifted from the immediate, face-to-face forms of play and game of the past, and continues accelerating, ever expanding into more domains of our everyday lives whether we choose to engage it or not. This expansion demands that play scholars take a hard look at all the different angles, components, and platforms that lead to moments and interpretations of active play.

I am grateful for the opportunity to dive into this and acknowledge the support of The Strong National Museum of Play’s Research Fellowship program, and Christopher Bensch and the committee for allowing me to study here.

By: Allen Kempton, G. Rollie Adams Research Fellow