You mark time when you ride a bike. Your mind drifts. It’s the rhythm, probably, the lulling tempo. My mind drifts as I ride the paved path along the blue Niagara River. By late summer I’ve put another fifteen hundred miles on the tires. Biking has always been play to me and my autobiography is composed partly in a succession of bicycles.

You mark time when you ride a bike. Your mind drifts. It’s the rhythm, probably, the lulling tempo. My mind drifts as I ride the paved path along the blue Niagara River. By late summer I’ve put another fifteen hundred miles on the tires. Biking has always been play to me and my autobiography is composed partly in a succession of bicycles.

My first bike was an ochre-colored machine with twenty-inch balloon tires and tan striping on the fenders. The color scheme didn’t seem to belong in the 1950s, but a tan decal outlined in black on the snazzy “tank” memorably named the bike Tempo. Learning to ride that bike made a lasting impression, literally. I learned to balance and pedal before I learned to brake. Thanks to the magic of Google aerial maps, I can still see (or think I might be able to identify) the tree that stopped my headlong progress down a slight hill in my old neighborhood. The scar has long since faded even as the hairline receded, but I still can feel the dent that the impact made in my forehead.

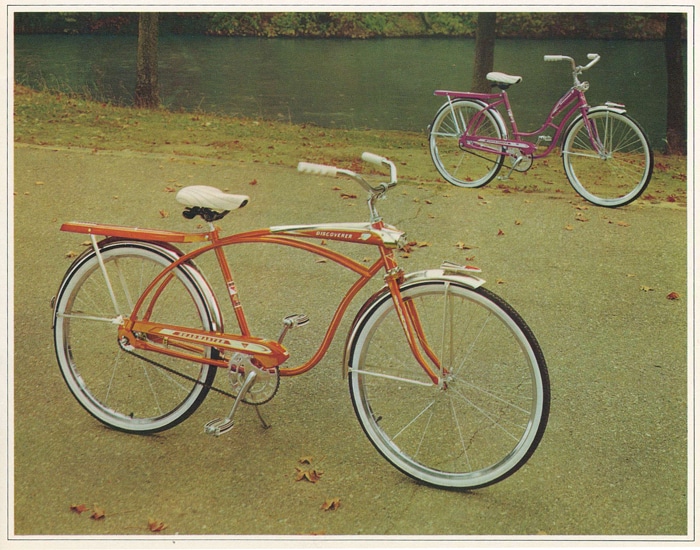

In time, a twenty-four-inch Murray replaced the Tempo. This new bike, bought to fit growing legs and a new neighborhood in a new state, sported silver fenders and a raked red frame that suggested streamlining and space travel. It transported my imagination even as it offered me the freedom to range my connected suburban streets. Those streets ended in bike trails through the retreating woods that lay at the rim of new housing development and the limit of civilization. Every neighborhood kid believed that the Fox Gang haunted this remnant forest, and that teenagers would seize unwary younger bicyclists and see to it that they either joined their band, or that they would never return. (The gangs in those days, much like the pirates we admired, were only imaginary.)

In time, a twenty-four-inch Murray replaced the Tempo. This new bike, bought to fit growing legs and a new neighborhood in a new state, sported silver fenders and a raked red frame that suggested streamlining and space travel. It transported my imagination even as it offered me the freedom to range my connected suburban streets. Those streets ended in bike trails through the retreating woods that lay at the rim of new housing development and the limit of civilization. Every neighborhood kid believed that the Fox Gang haunted this remnant forest, and that teenagers would seize unwary younger bicyclists and see to it that they either joined their band, or that they would never return. (The gangs in those days, much like the pirates we admired, were only imaginary.)

The last of my balloon-tired bikes was a sturdy, black Schwinn, heavy with post-war steel. Originally purchased at a Western Auto for fifty dollars, and ridden for all its worth, the Schwinn ultimately sold for five dollars at a garage sale twenty-five years later, having saved the planet tons of atmospheric carbon in between. Until winter weather set in, the Schwinn took me the mile to school in the morning, home for lunch, back to school, back home to suit up during football season, and back and forth from practice. My helmet hung from the handlebars.

That bike also took me to the big library four miles away where I discovered a treasure shelf of science-fiction books. I read the whole section through, chasing after adventure and immanence. After gulping down Twenty Eight Science-Fiction Stories—a thick volume that bounced out of the bike’s back carrier, scuffing the cover and earning a reprimand from the librarian—I eventually settled on H.G. Wells as my favorite author. Two years later, Wells’ Outline of History cemented an interest in the murky human past that eventually turned into a lifetime career.

That bike also took me to the big library four miles away where I discovered a treasure shelf of science-fiction books. I read the whole section through, chasing after adventure and immanence. After gulping down Twenty Eight Science-Fiction Stories—a thick volume that bounced out of the bike’s back carrier, scuffing the cover and earning a reprimand from the librarian—I eventually settled on H.G. Wells as my favorite author. Two years later, Wells’ Outline of History cemented an interest in the murky human past that eventually turned into a lifetime career.

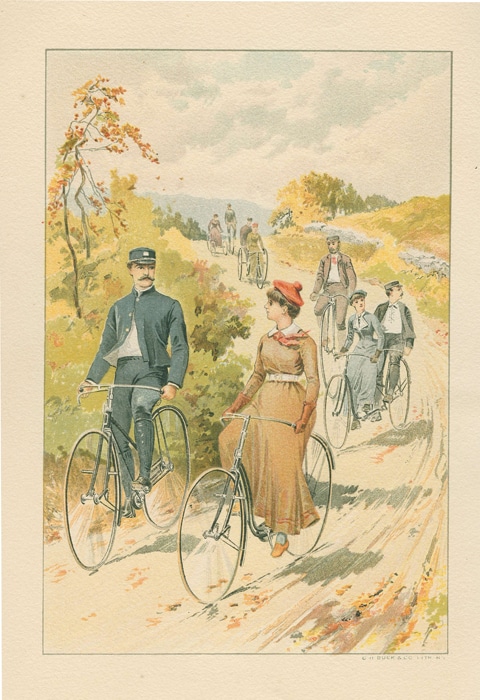

Along the way, and probably by accident since it wasn’t science fiction, I read The Wheels of Chance, a book that Wells wrote in 1895. That was the height of the first bicycle craze in Britain and North America when cheap, safe, and efficient bicycles first freed middle class men and women from the confines of the city, from train schedules, from elders’ prying eyes, and from stiff clothing. Split skirts—“rationals” as they were called—are an invention, a dress reform dating from this era. Looking at the novel again reveals that I’ve remembered only three things about it: the hapless main character’s name—“Hoopdriver;” the bad yellow bruises and scrapes he acquired falling off his bicycle; and the advice his teacher gave him: “avoid running over dogs.” These all appear in the first few pages, so it’s possible that I never read further. Since the story trails off into a rather treacly, thwarted romance and no alien beings ever manage to invade, the book may never have even left the library with me. But it’s Wells’ notice of the “psychology of bicycling” that catches my eye now. “To ride a bicycle properly … is a matter of faith,” he wrote. “Believe you do it and the thing is done; doubt, and for the life of you, you cannot.” Balancing a bicycle requires a distant attention that depends more upon muscles’ memories than the brain’s; and the principle reward for riding may be found in the pleasure of sustained balancing itself. Look ma, no hands.

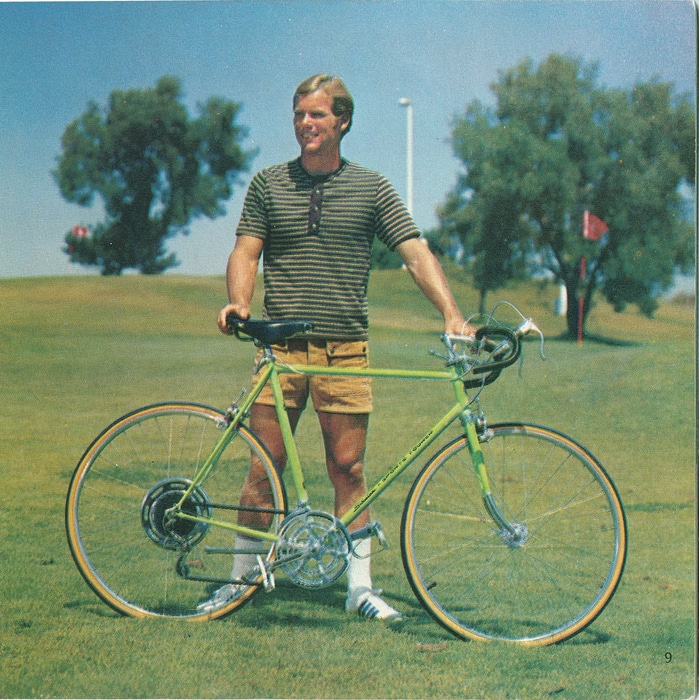

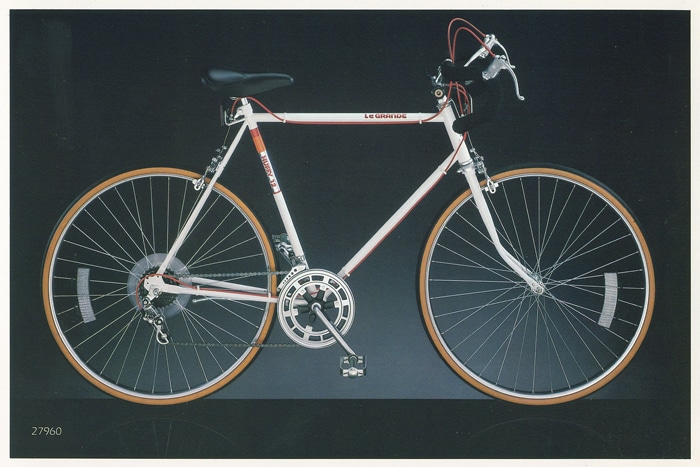

A beautiful metallic-purple, chrome-wheeled, second-hand Schwinn Varsity ten-speed replaced the utilitarian clunker and followed me to college whereupon, alas, enterprising bandits lifted an entire rack of bikes where mine was chained. Much later its replacement was stolen, too, but then hilariously retrieved in a story I cannot tell here.  The road bike that replaced that one, a gift many years later for a milestone birthday, seemed at first so exquisitely high tech and swift that it would be the last I’d ever pedal. But, during a charity ride, after two broken spokes and a bent wheel left me stranded in an area adjacent Indian Territory between Buffalo and Rochester—a place so alien and elsewhere that it is called the Alabama Swamps—the bike began to feel faithless and unreliable. So now a new, never-to-be-surpassed, light-as-a-feather two-wheeler with carbon forks and indexed shifting hangs in the basement, awaiting the first sunny weekend. To complete the bike-as-autobiography theme, this one is shamelessly narcissistic. Manufactured by Scott Bicycles, the name Scott appears in inch-high lettering on the frame, and then eighteen times more in smaller fonts in various spots on the bike. This may come in handy to remind me who I am as the bike carries me into middle age (middle if one expects to live to a hundred ten) and on into forgetfulness.

The road bike that replaced that one, a gift many years later for a milestone birthday, seemed at first so exquisitely high tech and swift that it would be the last I’d ever pedal. But, during a charity ride, after two broken spokes and a bent wheel left me stranded in an area adjacent Indian Territory between Buffalo and Rochester—a place so alien and elsewhere that it is called the Alabama Swamps—the bike began to feel faithless and unreliable. So now a new, never-to-be-surpassed, light-as-a-feather two-wheeler with carbon forks and indexed shifting hangs in the basement, awaiting the first sunny weekend. To complete the bike-as-autobiography theme, this one is shamelessly narcissistic. Manufactured by Scott Bicycles, the name Scott appears in inch-high lettering on the frame, and then eighteen times more in smaller fonts in various spots on the bike. This may come in handy to remind me who I am as the bike carries me into middle age (middle if one expects to live to a hundred ten) and on into forgetfulness.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.