How do you tell the history of video games?

For more than a decade, The Strong has been collecting, preserving, and interpreting the history of video games. Over that time our collection has grown to more than 60,000 video games and related artifacts, as well as hundreds of thousands of video game-related items in our archives. We’ve showcased them in exhibits, featured them in online content like our timeline of the history of video games, and made them available to scholars from around the world who have come to The Strong to do research.

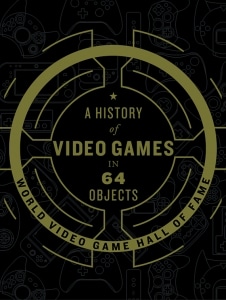

Now we’re highlighting this amazing collection with a new book from The Strong’s World Video Game Hall of Fame: A History of Video Games in 64 Objects.

The book uses 64 items from the museum’s collection to tell the story of how video games have changed, and how they’ve changed society. For me, one of the most challenging aspects of producing the book came at the very beginning—choosing which items to include and which to exclude.

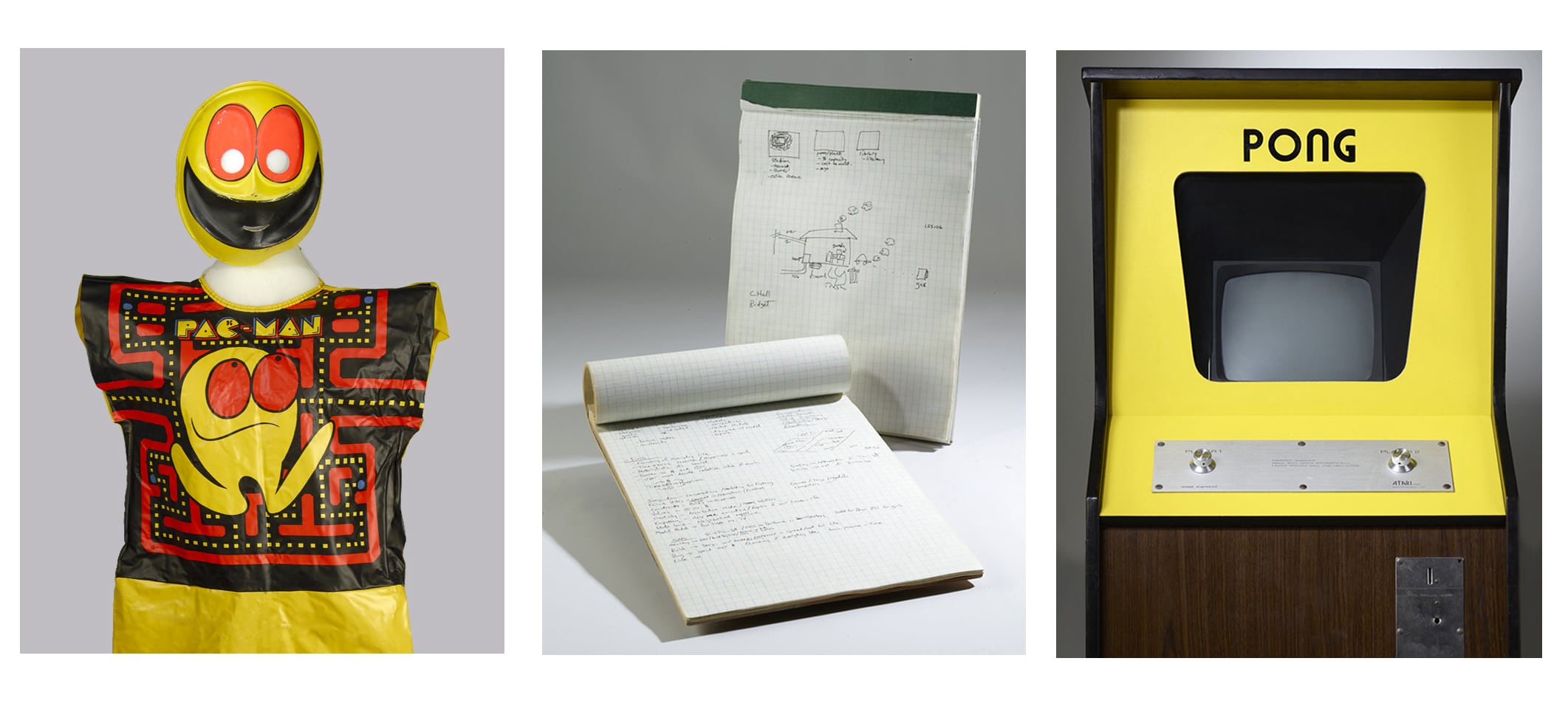

Some choices were easy. We knew we wanted to represent each member of the World Video Game Hall of Fame. Will Wright’s design notebooks for The Sims? Check. A Pac-Man Halloween costume (anytime something becomes a Halloween costume it’s probably of some cultural significance). A Pong arcade cabinet? Obvious. But after accounting for the games inducted into the first three classes of the World Video Game Hall of Fame, there were only 48 slots remaining in the book. How to pick 48 objects from the hundreds of thousands in the collection?

We chose some because they represented the work of pioneers. Humpty Dumpty, the first pinball with flippers, offered useful historical perspective about the development of the playfield. John Burgeson’s baseball game from 1961 was the first computer version of the nation’s pastime. Jordan Mechner used rotoscoping techniques to fluidly render human movement on a computer, and so it was natural to feature the photo prints he had originally created for that purpose.

We chose some because they represented the work of pioneers. Humpty Dumpty, the first pinball with flippers, offered useful historical perspective about the development of the playfield. John Burgeson’s baseball game from 1961 was the first computer version of the nation’s pastime. Jordan Mechner used rotoscoping techniques to fluidly render human movement on a computer, and so it was natural to feature the photo prints he had originally created for that purpose.

Other objects represented milestone games or symbolized an era. Thus anyone who grew up in the late 1970s and early 1980s probably played a handheld game like Mattel’s Football, owned a Texas Instruments Speak & Spell, traveled the Oregon Trail, or matched wits with Simon.

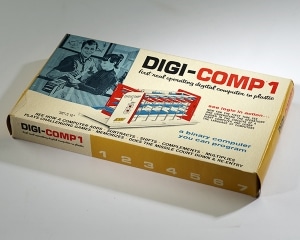

Some artifacts, our curators knew to be historically compelling. The Digi-Comp 1, which came out in 1963, billed itself as the “first digital computer in plastic” and offered kids the chance to write simple programs in binary, such as a rocket countdown and the game Nim. Produced at the height of the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union, it showed how grand geopolitical concerns often filtered their way into kids’ play.

Some artifacts, our curators knew to be historically compelling. The Digi-Comp 1, which came out in 1963, billed itself as the “first digital computer in plastic” and offered kids the chance to write simple programs in binary, such as a rocket countdown and the game Nim. Produced at the height of the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union, it showed how grand geopolitical concerns often filtered their way into kids’ play.

The Magnavox Mini Theater, the first retail display for a video game, opens a window into how manufacturers tried to make video games understandable to audiences who had trouble even conceiving what it meant to play a video game on a television. A game like Densha De Go, a Japanese train simulation game, shows how tastes in video games vary from place to place.

We easily could have filled a book with another 64 artifacts, but we’re excited that these selections provide not only an introduction to many of the games in the World Video Game Hall of Fame but also an introduction to gaming history as a whole.

So we hope you enjoy the book, available online from HarperCollins.

By Jon-Paul Dyson, Director, International Center for the History of Electronic Games and Vice President for Exhibits

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.