Employees at The Strong are fortunate to work in a place that encourages a fun and playful environment. It’s in our mission statement: “Through play, we encourage learning, nurture creativity, promote discovery, and transform the lives of people of all ages.” This applies not only to our approach to the visitor experience, but also to ourselves as we work.

As a member of the Collections team, I get to test games in the Infinity Arcade exhibit once a month before the museum opens. Gabriel Dunn, Conservator at The Strong, told me that the game testing serves three purposes, “It familiarizes the team with what is on display on the exhibit floors; it gives us time to bond and interact with one another in a fun atmosphere; and it gives conservation insight into how our games are currently playing and things that may need repairs, so we can keep a positive play experience for our visitors.” I would add the fourth purpose of giving me the opportunity to improve my scores on StepManiaX.

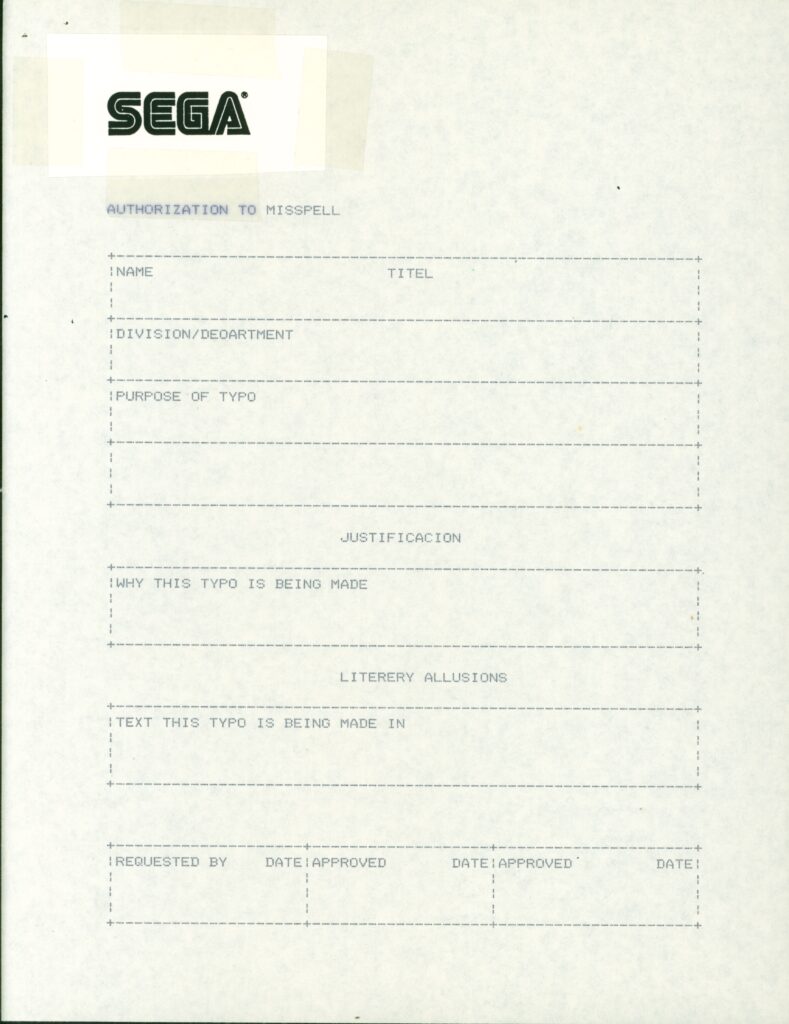

Our monthly arcade testing and other team activities [check out library cataloger Lindsey Barnick’s blog on our Dungeons and Dragons experience] are lots of fun, and they give valuable context to the collections we work with. In my specific role as processing archivist, I frequently find evidence in records documenting the creative ways employees of game and toy companies made time for a little fun at work. When I started at The Strong, the first collection I worked with was the papers of Tom Sloper, a game designer who has worked with numerous major developers throughout his career. Many archivists feel that we get to know the creator of a collection as we go through the documents and with Sloper this was quickly proven true. It is evident that he has a mischievous sense of humor that I appreciate. One of my favorite documents I saw in his papers is a satirical memo from “Sega” with the subject line “Revision to SEGA’s Misspelling and Typo Policy and Procedure,” which was filed along with an Authorization to Misspell form (101-6/84).

The memo begins, “From time to time, some SEGA employees may have occassion (sic) to misspell words in performance of their job.” It continues to outline the process of requesting approval for misspellings or typos with the company authorized Typo Agent. The memo has numerous errors distributed throughout the document itself including the “paige 2” header and the “telephane” number of the authorized agent’s office in “Los Angles, CA 99999.” Though I don’t know for certain that Sloper was the author of the memo and form, finding them in his files gave me the feeling that I’d enjoy having him as a coworker.

My most recent project is processing the company records of Quicksilver Software, Inc. The collection is extensive, estimated to be more than 80 linear feet, and is comprised of many materials in different formats. Documentation of Quicksilver’s work on games, devices, and online systems has enormous research potential, and all the fun that evidently happened in their offices adds more value to our institution’s focus on the study of play. I have come across phony memos, joke awards distributed among coworkers, clippings of comic strips—so many Dilbert clippings!—and plenty of notes and doodles. I really enjoyed reading some humorous newsletters written by office manager Katie Fisher, where a recurring topic was her own writer’s block (relatable). It may not be surprising that game development companies like Quicksilver have fun environments, but I suspect that all kinds of workplaces have some playfulness hidden within their records.

During working hours, our productivity and creativity can flourish when we make time for our natural playfulness. Finding evidence of the benefit play has for people at work is part of what makes my job in the archives so much fun!