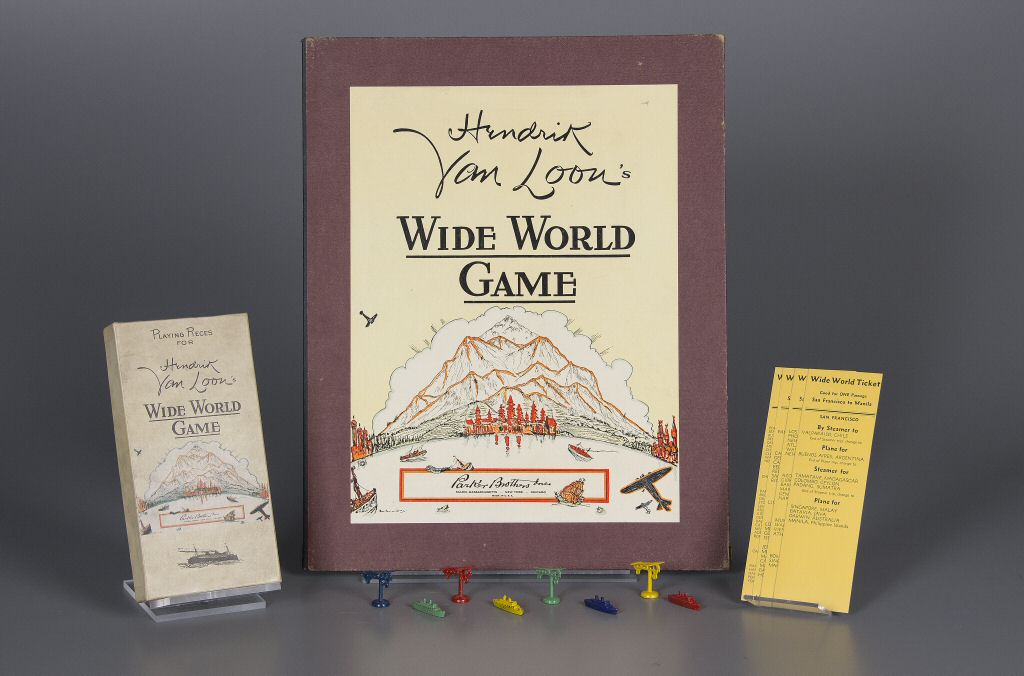

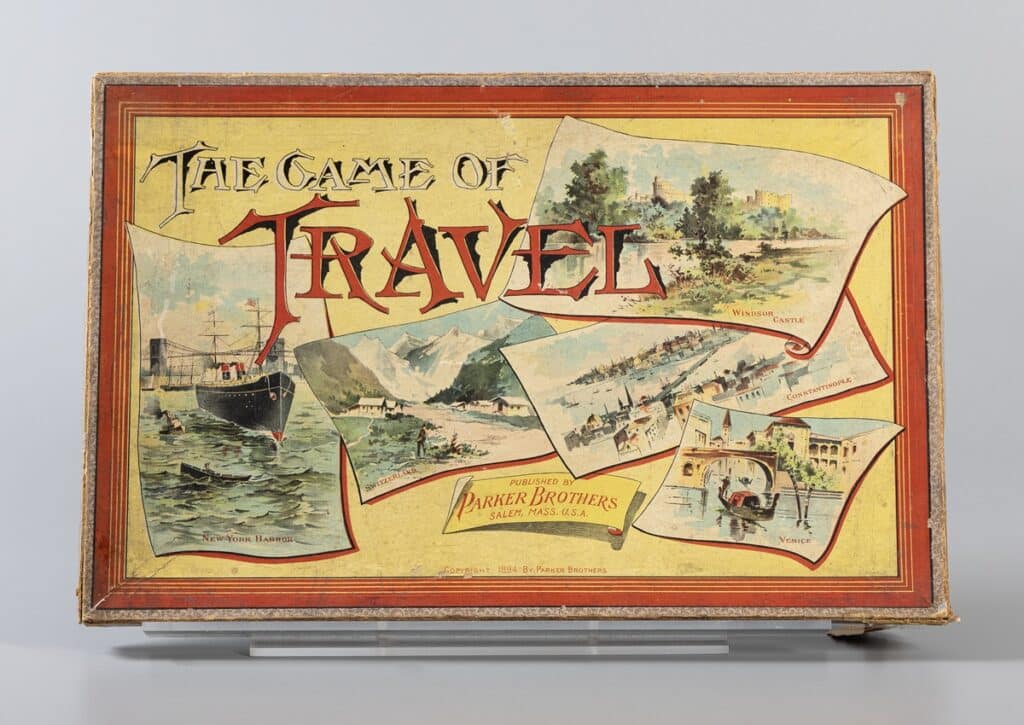

Have you ever played The Game of Travel? I’m willing to bet you haven’t. It was published in 1894 by Parker Brothers, perhaps most famous for manufacturing Monopoly. How about Hendrik Van Loon’s Wide World Game? That Parkers Brothers game is from 1933. For 2025’s International Day of Play, I teamed up with members of our collections and public programs teams to offer guests the opportunity to play these rare games. Let’s talk about why I chose these games and how we went about creating playable reproductions.

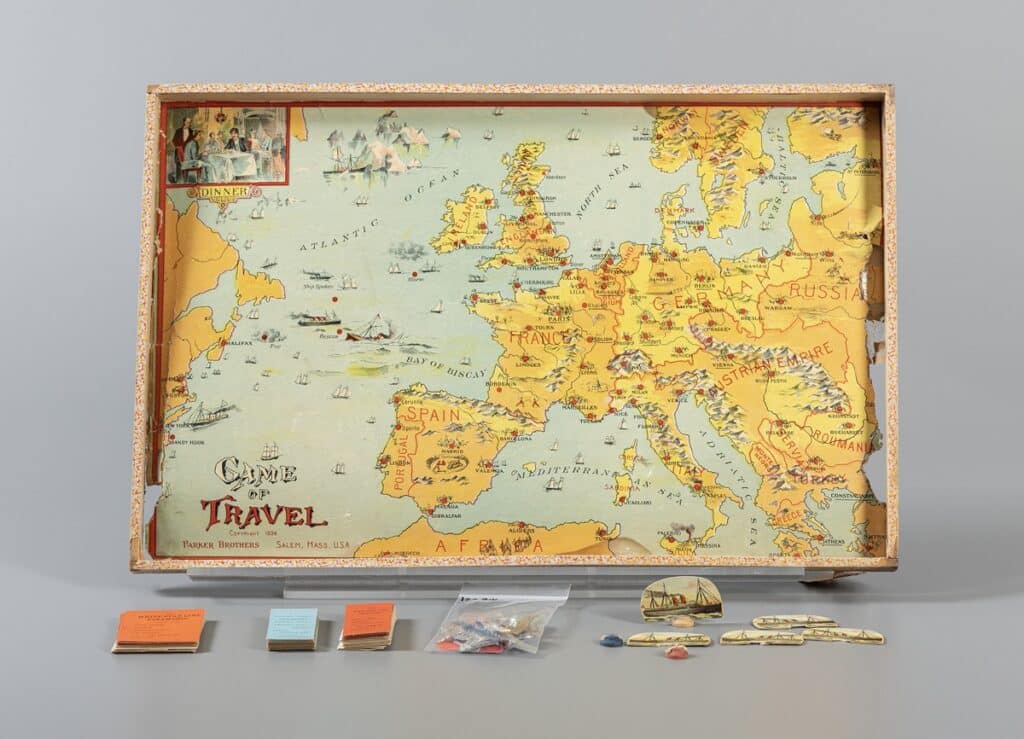

Appropriate for International Day of Play, the goal of each game is to travel across countries and oceans. In The Game of Travel, players draw tickets with a list of locations. On a player’s turn, they proceed to the next location on their ticket. Once they’ve visited each location on the card, they draw a new ticket that takes them on the next leg of the journey. Players win by visiting Constantinople (now Istanbul) and returning to the United States. Named after historian and children’s book author Hendrik Van Loon, the Wide World Game was released almost 40 years after The Game of Travel. Fittingly, given its title, the game features a wider world than its predecessor. While The Game of Travel restricts players to Europe and the Atlantic Ocean, the later game’s routes take players across every continent except Antarctica. Here, the goal is to be the first to travel from San Francisco to Manila. The Wide World Game follows the same basic flow of moving between cities according to one’s tickets.

Both games were influenced by the increasing availability of international travel around the turn of the 20th century. Alongside technological developments and Gilded Age economic changes, the number of issued U.S. passports increased significantly in the late 19th century. Steamships and trains made travel more accessible to a growing middle class. Such methods of travel are highlighted in the games through an unusual feature. The Game of Travel has players swap out their moving marker according to the method of travel: a train when traveling by land, a ship if by sea. Since the games are so similar, though, it’s interesting to see where they differ. The wide world changed between 1894 and 1933. By the 1930s, there were several commercial airlines in the U.S., and with new forms of travel come changes to the rules. The Game of Travel requires players to move one city at a time, but the airplane in the newer game lets players move through as many as six cities in a single turn!

Guests could appreciate many things about the games if we showcased them in a display. The Game of Travel is a beautiful production. Its cover features painterly illustrations of attractive destinations like the canals of Venice and England’s Windsor Castle. Its metal steamships shimmer in the light. The Wide World Game’s stylized world map appears hand-drawn with vibrant colors. I’m sure guests would be delighted to see them. With interpretive labels, we could provide some information about the games’ rules and historical context. But games are meant to be played.

To be clear, not even I get to play the games in our collection. This is for good reason, although I’m often dying to give the games a try. For one, many of them are fragile. The Game of Travel was printed more than 100 years ago, and it shows. The board is coming off in flakes, leaving holes in eastern Europe. We wear gloves when handling artifacts not just to protect the objects, but also to protect ourselves. The malleability of the steamship tokens hints that they are likely made of toxic metals, and paint used in the Wide World Game is probably also dangerous. So, how can we have guests engage with these historic games without putting them or the games at risk?

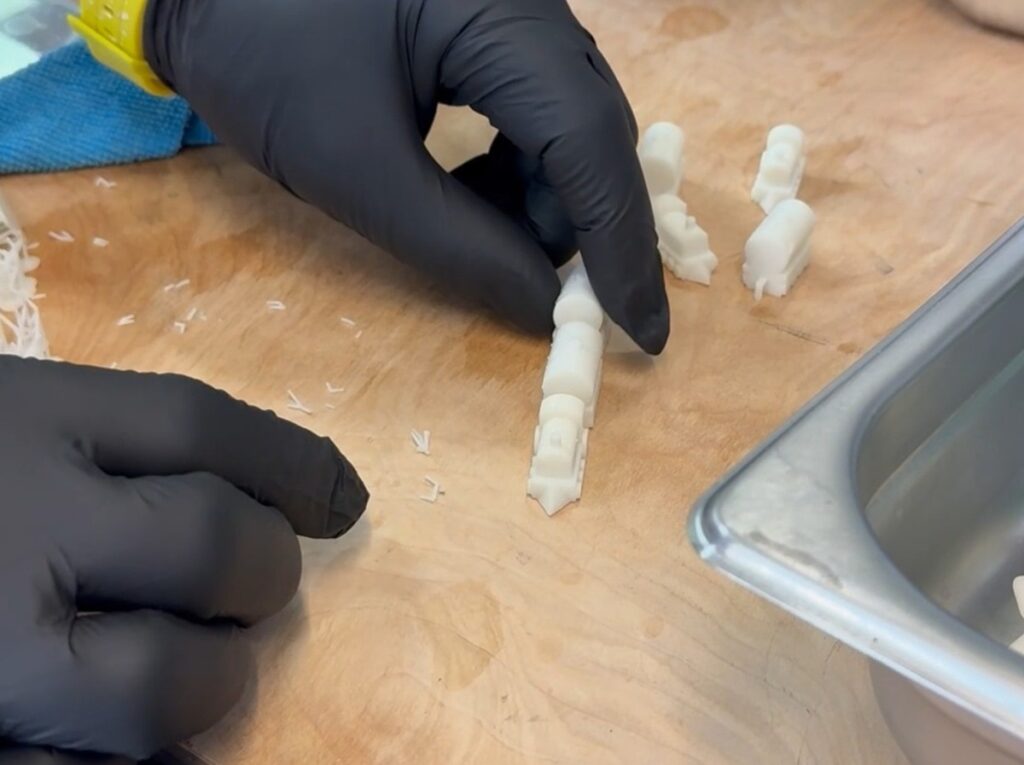

We chose to create our own versions of each game. Making the copies required collaboration between multiple teams at the museum. First, I scanned the games’ boards and cards and sent the scans off to Corinna, one of our public programs coordinators, to fabricate those components. They pasted the boards to a large piece of cardboard and printed out and laminated the cards. Meanwhile, Martin, our arcade game conservation technician, began 3D printing trains, planes, and ships using a resin printer. Martin’s trains are a real highlight, featuring little linked cars that follow behind the locomotive. After laminating the cards and sealing the boards, our more robust versions of the games were ready to be played with by childhood hands.

Our International Day of Play programming was a success. I delivered a small presentation showcasing the original games, along with some other travel-themed games and puzzles, while our associate curator Natalie gave a fascinating talk about postcards and souvenirs. The reproduced games were available to play all day. The preservation of board games is important. Researchers come from across the globe to study our collection. But there are probably very few living people who’ve actually played these games. I’m excited that we gave our visitors a chance to join that exclusive group.