I arrived at The Strong National Museum of Play hoping to uncover more about the history of music in early video games—especially those released before 1985, the year the Nintendo Entertainment System launched in North America. I was particularly interested in games created by Atari in the 1970s and early ’80s. Many accounts of video game music history follow a familiar narrative: sound moves from silence to fully integrated musical scores, evolving in lockstep with technological advances. It’s an appealing story—a steady march toward sophistication—but I wondered whether it was too tidy. Was music truly a priority for early game developers, or are we imposing a teleological narrative in hindsight, projecting our present-day assumptions onto a past that never shared them?

Over the course of a week immersed in The Strong’s exceptional archives—including the papers of Carol Kantor, Carol Shaw, Steve Kordek, and Mark Lesser, as well as an expansive collection of Atari design documents and internal memos—I began to see these questions in a new light. The word music appears rarely in these early materials, and when it does, it’s often interchangeable with other terms—sound, tone, jingle, beep, tune, even thump. At times, what we would now call a sound effect is labeled as music in developer notes. These documents aren’t sloppy—they simply come from a time before today’s distinctions between “sound effects” and “music” had crystallized in game design discourse.

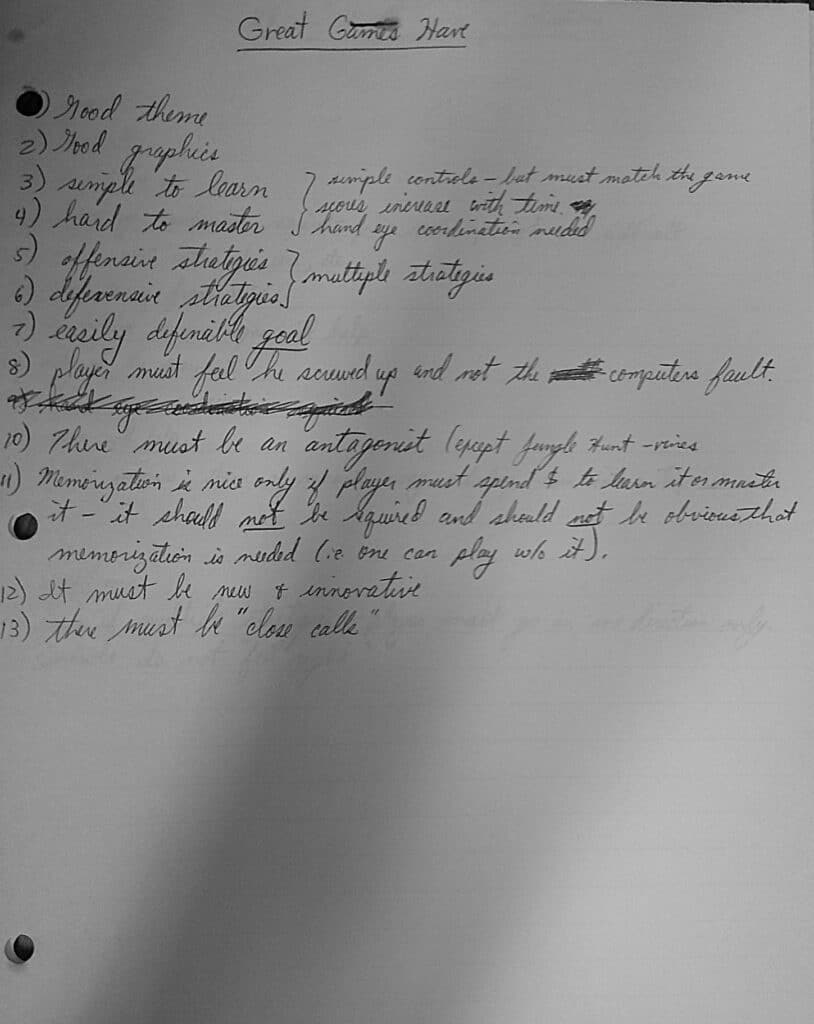

What struck me most was how little evidence exists that music was seen as essential to game design in the first place. It’s not just that it was technically difficult to implement; it doesn’t seem to have been a conceptual priority. A handwritten page of notes by Ed Logg—creator of Asteroids and Centipede—lists qualities of “Great Games” but makes no mention of sound at all. Elsewhere, Atari’s internal memos go months at a time without referencing audio. Sound was present, of course, but it was rarely dwelled upon.

More telling still is a 1980s press release for Atari’s 5200 console, which trumpets two “revolutionary features”: a Trak-Ball controller and a Voice Synthesizer module. The release boasts that voices would become “an integral part of game play, not just a sound generator,” promising “the ultimate in video game realism.” It’s hard to miss the implication: the sonic future Atari envisioned was one of simulated speech, not music. Voice, not melody, was framed as the pinnacle of immersion.

This reorients the traditional narrative. Perhaps the Holy Grail of early game sound wasn’t music at all; perhaps it was voice. From that perspective, adding background music to a perilous jungle or the far reaches of outer space might have seemed artificial—or even at odds with the era’s growing emphasis on realism in game design, a trend that became especially clear during my time at The Strong. This raises broader questions. To what extent have our expectations of game audio been shaped by film, a medium in which music gradually came to be understood as essential? And what does it mean when the soundscape of early games resists those same expectations?

I haven’t finished puzzling through these questions. But that’s precisely what made the fellowship so valuable: the time and space to reflect, reframe, and reconsider.

One of the greatest pleasures of my week in this regard was the camaraderie that developed with fellow research fellow Kristin Fitzimmons. Though our projects came from different disciplines, our daily conversations—sometimes at the archives, sometimes over dinner—became a kind of informal salon. We exchanged observations, challenged each other’s assumptions, and helped refine the ideas that were still half-formed in our own heads. In a field like mine, where research is often a solitary pursuit, that kind of dialogue was invigorating. It sharpened my thinking and reminded me that scholarship isn’t just better when shared—it’s shaped by the sharing.

By: Andrew Schartmann, 2025 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow at The Strong National Museum of Play