This season of make-believe and dressing up is a good time to think about pretending—one of the cornerstones of play. For kids, make-believe is partly aspirational. If you’re little and you dress as a crime fighter or superhero you take in the fantasy, feeling power surge in your imagination. You have nothing to fear, even fear itself. Bad guys beware. And so too the ghostly hosts that will roam our neighborhoods this Halloween, scary in themselves, scaring off fear. They’ll join pretty princesses and piratical pirates, robed mythic villains and fierce, fuzzy lions and tigers. For kids, the question “what are you going to be?” adds a dimension. Kids often wonder what they are going to be, and though few (or none) will ascend a throne or command a ship harrying the Spanish Main, they imagine competence, respect, even power.

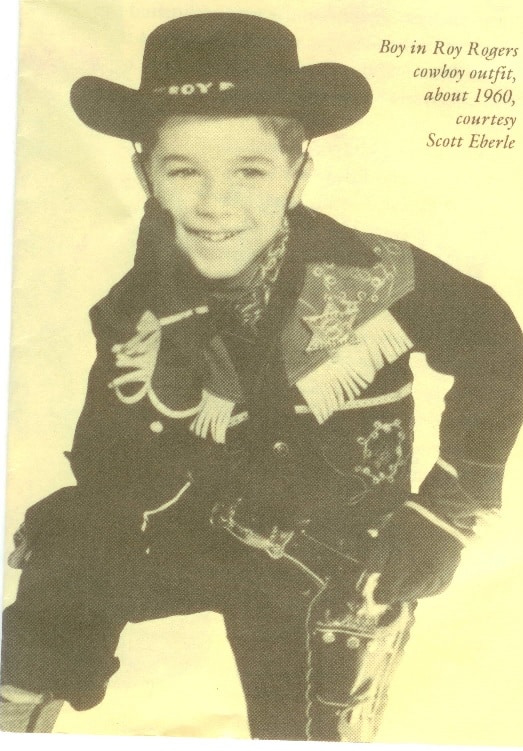

For my sixth Halloween I went as Roy Rodgers, the singing cowboy, “King of the Cowboys,” who on horseback ran rustlers and bushwackers to the ground even though they sometimes drove jeeps. A year later Halloween was all about pirates, guys so bad they were great!

For adults pretending is different, of less moment usually, but often more complex, ironic with less hero-worship mixed in, allusive, humorous, and transgressive. A colleague of mine will glitter up this Halloween as a Space Girl, her skirt a supernova, her antennae tuned for monsters from beyond. And her friends will go as Yo Gabba Gabba guest-stars, or farmers dressed as the Grant Wood couple with their baby outfitted as a pumpkin. Another young family will appear as Dr. Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, and baby as Frankenstein’s monster.

This year many adults will go to parties as zombies, not a state anybody would aspire to surely, but a costume that co-opts the various dark fears our popular news media now thrives on.

Thinking about zombies got me thinking about two other things—one of Mark Twain’s short stories, “The Curious Dream” and a party 30 years ago.

In the tale, Twain himself dreams of an encounter with a walking figure—a tall, hooded skeleton dressed in a moldy shroud. The skeleton laments his property gone to ruin. The graveyard is so scandalously ill-kept that the wraith, once resting at ease, now wishes he’d never died. Twain’s real purpose in this minor work of fiction was to publicly lampoon the shabby condition of a real burial ground that the growing city where he lived and wrote, Buffalo, had grown around.

This story and its skeleton always reminds me of a recurring yearly Halloween party that, more than a 100 years later, took place at a once-elegant Victorian manor located just a few doors down from Twain’s old house on the same city’s grand Delaware Avenue. The nearby mansion—cut into apartments in the mid-1980s and by then known as Victor Hugo’s—hosted the second hippest Halloween party of that era. The residents at Victor Hugo’s would open their doors to all celebrants who came in costume.

And yes, in these parties that now run together in memory, I do remember some skeletons. And they were only the beginning; year after year the event attracted partygoers from the city’s thriving theater community who delighted in their costumed transgressions. I remember a tall man in a Ronald Reagan mask, avuncular except for the sharpened incisors and the toy rocket that hung on a lanyard around his neck. To balance political irreverence, a Jimmy Carter wandered in carrying a pint of Kahlua in his suit coat pocket. There was a Pam Grier lookalike from the Foxy Brown era wearing platform pumps and an orange jump suit with elephant bellbottoms; she was accompanied a guy gotten up as George Wallace, the prominent segregationist. A couple of fake nuns arriving as a couple startled me (personally) even more with the exactitude of their habits and the reproving way they stayed in character. Some more of the adult costumes that I can’t tell you about transgressed quite a bit further.

On a sliding scale, these satirical presentations lay at the other end of play from the spunky or spooky kids’ get-ups. But the two approaches—childish delight in spookiness and adult glee in mischief—shared intent; both meant to take the powerful down a peg, turning the world upside-down with make-believe and farce.