Escape rooms are a massive commercial industry. In 2024, the Escape Room Industry Report counted approximately 2,000 facilities in the United States alone. They’re also massive physically—these in-person experiences are room-scale. As The Strong begins an initiative to preserve escape room materials, we’re starting small. Many creators have attempted to capture the magic of the escape room in a packaged product. These games show that escape rooms, and games based on them, do not fit neatly into a box.

As I catalogued a collection of these at-home escape room games at The Strong, labels began to fail me. While some were certainly legible as board games, others stretched the limits of the term. I’ve faced similar challenges before. In 2021, I published a paper about “escape games,” a broad genre label I applied to digital and analog games in which players solved puzzles to escape from a room. Some of the earliest live-action escape rooms were inspired by online “escape the room” adventure games, and the escape room has itself inspired virtual reality and at-home versions. I suggested the term “tabletop escape games” to refer to portable escape room games designed for play in the home or classroom rather than dedicated escape room facilities. I’ve since switched to the term “escape box” because I believe it better represents the breadth of approaches at play. As we’ll see, many of these games leave the table behind.

But what is it that escape box creators are trying to capture? Scholar and game designer Scott Nicholson provides the following definition of escape rooms: “players trapped in a space [have] to rely upon their wits and each other to find hidden objects, solve a series of puzzles, and accomplish tasks to get out in a certain amount of time.” The live-action escape room facilities counted in the Escape Room Industry Report are buildings players visit to play the games, but board game publishers and escape room companies have also endeavored to adapt the experience for the home. The key elements in Nicholson’s definition, including puzzles, cooperation, space, hidden objects, and time limits, manifest in various forms and to differing extents in each of these at-home games.

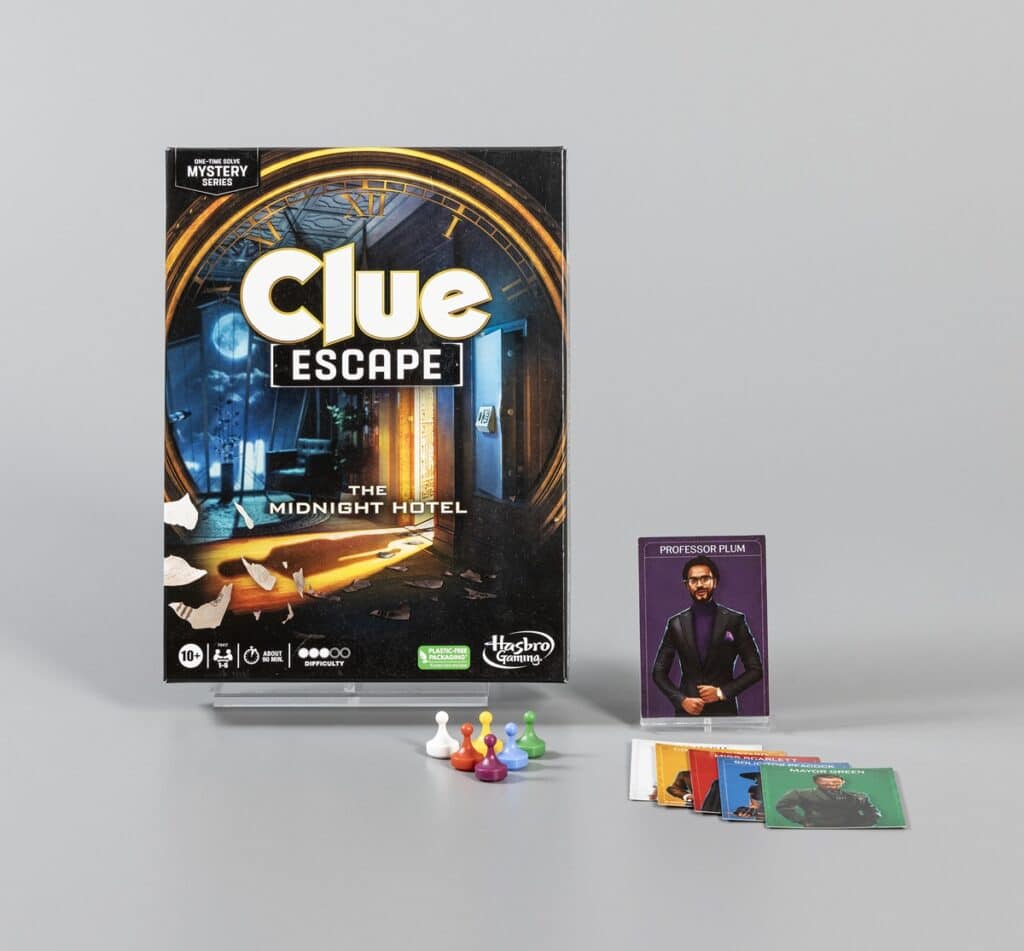

Some escape boxes attempt to emulate escape rooms while hewing close to board game conventions. Clue: The Midnight Hotel is a spin-off of the classic board game Clue that, like Clue, tasks its players with solving a three-part mystery by searching for clues in a series of rooms. After selecting a character and the matching plastic pawn, players take turns exploring the rooms of the Midnight Hotel. The game merges the classic board game with the collaboration and puzzle-solving emphasized in Nicholson’s definition. As players explore, they draw cards that introduce objects used in puzzles or provide clues necessary for solving the final mystery. Clue’s competitive race to deduce the culprit is replaced with a cooperative puzzle-solving experience. One might expect an escape box developed by an escape room company to depart more drastically from what we expect from a board game. The Escape Game, one of the largest escape room chains in the United States, released their own escape box, Escape from Iron Gate, in 2019. However, Escape from Iron Gate also draws primarily from board game conventions. While the game includes puzzles and ciphers, it also incorporates elements of classic party games like Pictionary and charades. Like many board games, but unlike most escape rooms, the game is competitive; only one player can escape the titular prison.

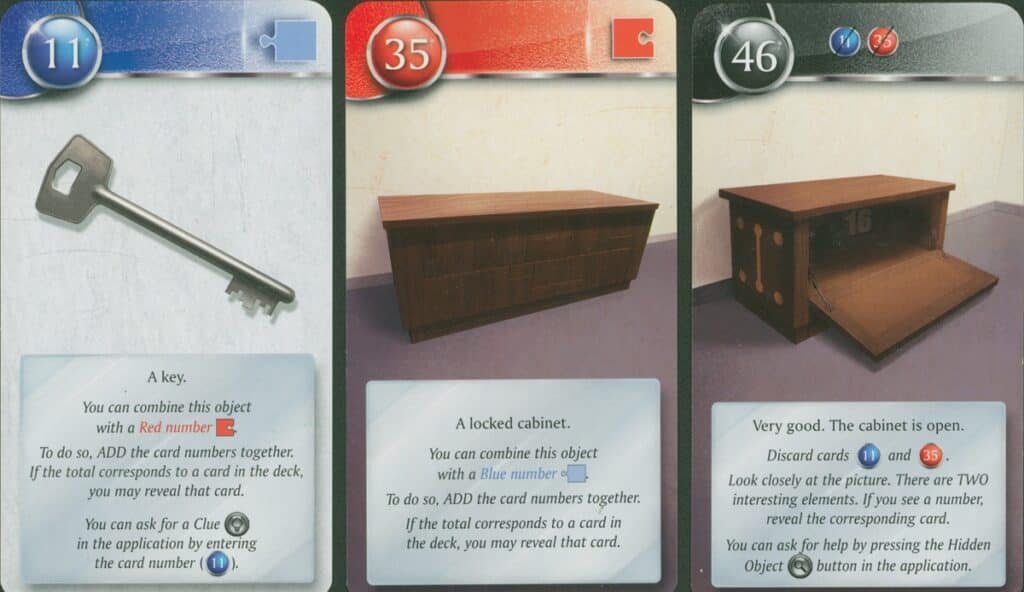

Other escape boxes appear to be conventional board games before quickly subverting those expectations. While many make use of standard game components like cards, they often break with the way those components are typically employed. Nathan Altice’s article “The Playing Card Platform” identifies properties of playing cards that enable common forms of gameplay. The randomized shuffling that is core to so many card games is possible because the cards are uniformly shaped, and the card backs are indistinguishable from one another. Many escape boxes, however, intentionally abandon these properties. The cards in Space Cowboys’ Unlock! series, for instance, are not uniform; each has a unique number prominently featured on the back. This unusual characteristic enables an interesting item combination mechanic that harkens back to the digital adventure games that inspired early escape rooms. As the players accumulate items, they can use them with one another. To combine two items, players add the numbers of the two cards together and reveal the card matching the sum. Combining the tutorial mission’s card 11, a key, with card 35, a locked cabinet, reveals card 46: the cabinet, now unlocked. By abandoning a core element of card games, Unlock! introduces a novel puzzle-solving mechanism that brings to mind both the live-action escape room and its digital predecessors.

Rather than repurposing conventional game components, some other escape boxes introduce unusual game pieces. These games blur the boundaries between the players and the fictional world. Escape rooms are all-encompassing. When the door is closed behind the players, they are cut off from the outside world and surrounded by a fictional one. Escape Room in a Box: The Werewolf Experiment achieves a similar effect by foregoing the components of the usual tabletop game entirely. The game world’s objects are represented not with cards or tokens but with plastic petri dishes and locked metal tins. The use of bespoke physical objects is again reminiscent of adventure video games. Many classic adventure games came packaged with maps or other physical objects called “feelies.” In her article “The Treachery of Pixels,” scholar and historian Carly Kocurek argues that feelies operate as extensions of the game world. “Players can handle a feelie and by extension, at least in a small way, touch the world of the game—which in turn, via the feelie, extends into the players’ lived world.” Although escape boxes cannot physically envelop the players like live-action escape rooms, they have found their own ways to bring players into contact with fictional worlds.

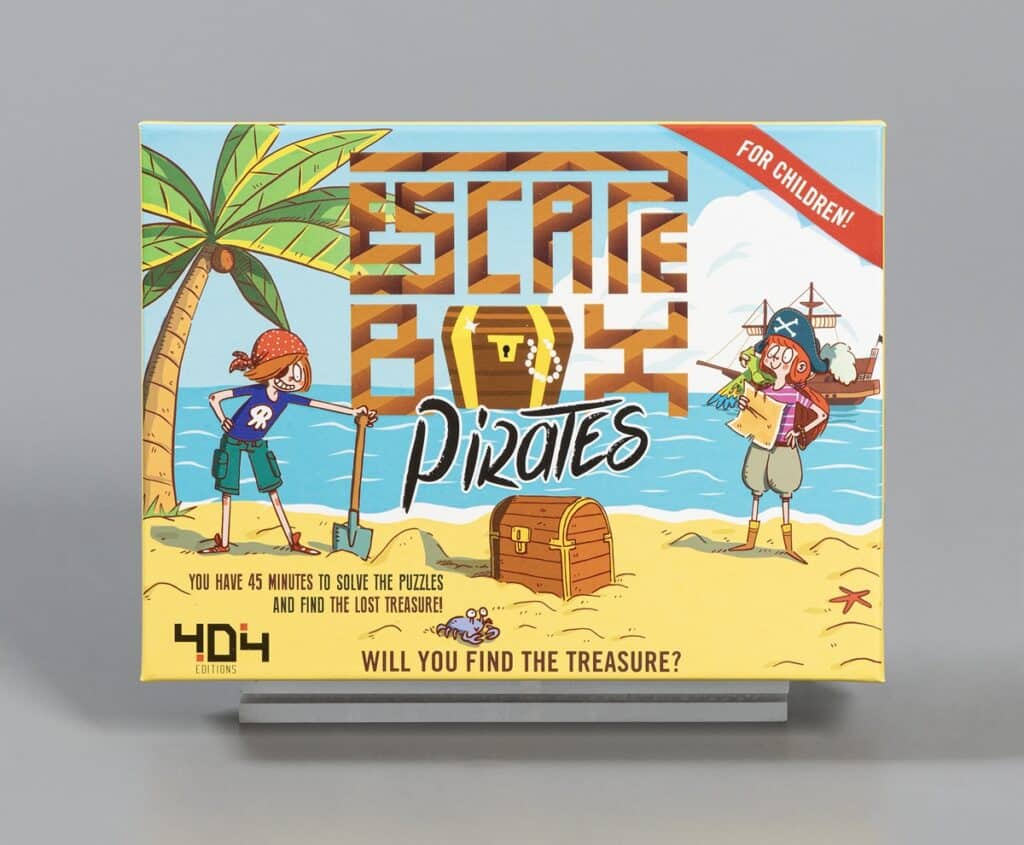

Some games go as far as to abandon the table entirely, subsuming the surrounding playing space into the game’s fictional world. There are no plastic pawns on a board, here. Instead, both Escape Box: Pirates and Escape Your House: Spy Team require a game master to position the game’s cards throughout the room itself. Spy Team goes a step further by utilizing multiple rooms. The game includes one primary lock meant to be hung on the front door as well as several cardboard doorknob hangers that “lock” off other rooms. In the game’s fifth mission, the players’ home becomes the Hackers’ Hideout. An ordinary living room or bathroom transforms into the hideout’s server room or control room. In these games, the exploration of physical space is paramount to the escape room experience. These games differ, though, in their approach to objects hidden in that space. Escape Box: Pirates sees the search for hidden objects to be crucial to the escape room experience, instructing the game master to hide the cards for players to find. Spy Team asks the game master to make its cards clearly visible, focusing the players’ attention on using the cards rather than finding them.

Finally, escape boxes also vary in how they approach time limits. The almost ubiquitous one-hour time limit imposed by escape room facilities is a scheduling convenience that allows groups to sign up for hourly time slots. The pressure of the ticking clock is seemingly so integral to the genre, however, that it appears in many escape boxes, which do not have to adhere to scheduled time slots. The turn-based structures of The Midnight Hotel and Escape from Iron Gate stand out in comparison to the frantic real-time puzzle-solving of many of the other games. The Unlock! series requires a mobile app that counts down the players’ remaining time. The underwater adventure The Nautilus’s Trap makes clever use of the clock, utilizing it to represent the oxygen remaining in the players’ air supply. Starting with only 35 minutes, players can add to the timer by finding oxygen tanks hidden throughout the card art. But unlike the live-action escape room, you can keep playing these games even after clock runs down. I won’t tell.

From the components they use to the ways they handle space and time, escape boxes are indicative of varying understandings of the escape room genre. Are these games about immersion in a fictional world? About finding hidden clues? About teamwork? That escape boxes tackle the challenge of adaptation in such differing ways makes sense, given the myriad influences that shape live-action escape rooms themselves. Scott Nicholson’s 2015 survey of escape room facilities revealed that creators were inspired by video games, interactive theatre, live-action role-playing, movies, and TV shows, among others. Neither escape rooms nor the games inspired by them are monolithic. Even the goal of escape is not universal. Live-action escape room designers have refused to limit themselves to tales of escape—Nicholson’s survey also found that 30% of rooms did not require the players to escape a room at all.

By combining elements from board games and escape rooms, escape box creators make games that do not fit neatly into either category. Designers continue to explore the edges of these genres. Some are investigating ways in which other forms of play might intersect with escape rooms. The Toy Factory, a jigsaw puzzle in Ravensburger’s Escape Puzzle series, adds a short narrative hook to the puzzle-solving experience and hides riddles and clues in the completed image. Other creators are reversing the adaptation process, instead designing escape rooms based on board games. In 2024, live-action escape room company Breakout Games teamed up with Hasbro to create an escape room based on Monopoly. Working in this nebulous space between genres requires thinking outside the box.