If you were to replace the original raster monitor on a vintage Pac-Man arcade game with a modern LCD display, would it still be the same game?

That’s the sort of choice we often must consider as we care for the hundreds of coin-operated games in our collection at The Strong, and while the answer is rarely straightforward, the process of thinking it through is instructive as to the larger question of how you preserve a video game, especially arcade games.

A coin-operated game is a physical object made from many components—they could be plastic, pressboard, a television monitor, graphical overlays, controls (some standard, some specialized), electrical and electronic components, and many other materials. None of these things will last forever, but they all must somehow work together to provide the proper play experience. As the scholar Raiford Guins has pointed out in books such as Game After, arcade games are both material and virtual objects, and anyone preserving them must figure out how to balance the need to honor the game’s history and original instruction with the ongoing need to keep it operational. That’s often a tricky balance to maintain.

Consider an arcade game like Pac-Man that came out in 1980. Although a printed circuit board operates the game along with a variety of other electrical and electronic parts, users primarily interface with the game through four classes of components: the cabinet, the controls, the speakers, and the screen. Each of these pose preservation challenges on both a practical and philosophical level, requiring the museum’s conservation team to make choices, in consultation with other colleagues from the museum’s International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG).

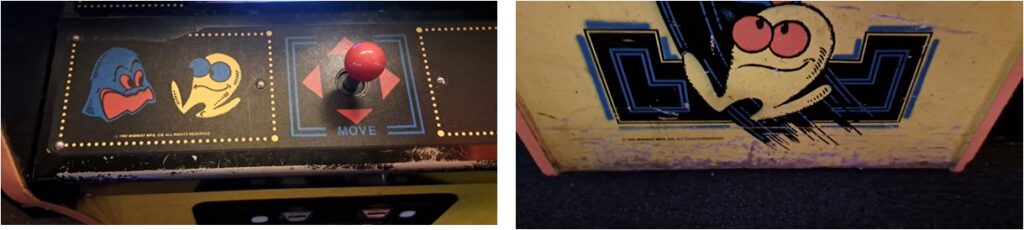

Let’s begin with the cabinet, as that’s how the game presents itself to the world. The cabinet was designed to entice people to walk over and drop in a coin. Usually composed of medium-density fiberboard (MDF) with overlaid paint, printed graphics, and some lights in the marquee, the cabinet preserves a history of the tens of thousands of interactions players have had with it. For example, our copy of Pac-Man that is playable in The Strong’s Infinity Arcade exhibit discloses that countless shoes have scuffed the paint, and the spots where players rested their free hand (Pac-Man only requires that players maneuver a joystick, not use both hands to play) are worn, such as on the front edge of the control panel. While sometimes our conservation team will repair or repaint surface damage, often we leave this wear as a patina of use. Every nick tells a story.

And yet other things we will swap out more readily. If the speakers go, we will swap them for new ones by the same manufacturer if possible. Looking at the conservation record for this Pac-Man game, I see that in 2023 our conservation technician replaced the lights in the marquee. Similarly, if the joystick were to break or one of the buttons stopped functioning, we would replace those with readily available modern Happ controls that look and act like the originals. A Pac-Man game without a working joystick would be no fun at all. But what happens if modern replica parts are not available?

Recently, for example, our conservation team has been repairing our Quick ‘n Crash shooting game. The gun that players use has broken and it’s hard to get an original replacement. So, the team has been scanning the original and 3D printing a replacement so that guests can repair it again. Is that somehow a violation of the integrity of the game because we’re using a modern replacement part? I think not.

That brings us to the monitor, the most significant way in which players interact with the game. Namco’s designers built Pac-Man to run on a cathode ray tube (CRT or raster) monitor. When the game came out in 1980, that was the most popular means of projecting an image on a screen, and so it made sense to use that particular display technology. Consequently, when creating a game to play on it, programmers kept in mind the way that the device created an image by rapidly lighting a screen with an arm that swung back and forth in quick succession to cast lines. The computer running the program had to account for this electronic functionality, so the images needed to work in such a way that they rendered correctly on the monitor.

But what happens when the quality of a Pac-Man monitor becomes too poor or breaks altogether? As I noted already, components do not last forever. Fuses burn out, wires fray, plexiglass cracks, switches fail, and monitors die. They need to be replaced, but what can be used to replace them? We can 3D print a new gun for Quick ‘n Crash, but we can’t 3D print a working CRT. And yet the monitor may make a difference in how the game looks. LCDs offer higher definition than the old raster monitors, which sometimes make old games look pixilated. Likewise, old monitors curved gently, while modern LCDs are flat. Pac-Man viewed on a modern screen just looks different than one played on an original CRT.

So it would seem best to replace the original raster monitor with another raster monitor. Indeed, people passionate about this subject often consider it sacrilege to put an LCD into an original machine. Yet it’s getting increasingly hard to acquire 19-inch raster monitors and will only get harder in future years. Back in 2012, on hearing that the last North American CRT factory was closing, The Strong stocked up on 30 new, in-box raster monitors for our arcade games. With this supply, and the fact that we actively rehabilitate old ones, we haven’t had to replace a CRT with a flat screen yet. But even if we use a rehabilitated monitor, there’s no guarantee a 30-year-old monitor will have the same crispness and color it did new. The image on original monitors may look faded, just as the paintings of the Sistine Chapel—before they were restored—darkened with age. At some point, we may need to resort to using a flat-screen monitor, though we may be able to use a scanline generator or other tricks to make it look like an original CRT.

These types of conservation dilemmas are not unique to vintage video games. Consider an old house. Should a historic home be preserved in exactly its original condition? Is it ok to preserve the leaded glass windows but replace the lead pipes? And what is the “original” condition? Should a house be preserved at the point when it was first built, or when its most famous inhabitant occupied it, or as it was later modified?

Howard Mansfield in his book The Same Ax, Twice offers a perspective on handling such issues of preservation. He cites the example of a farmer “who says he has had the same ax his whole life—he only changed the handle three times and the head two times. Does he have the same ax?” Mansfield concludes that yes, “He possesses the same ax even more than a neighboring farmer who may have never repaired his own ax. To remake a thing correctly is to discover its essence.” Mansfield continues, “A tool has a double life. It exists in the physical sense, all metal and wood, and it lives in the heart and the mind. Without these two lives, the tool dies. The farmer who restored his ax has a truer sense of that ax. He has the history of ax building in his hands. Museums are filled with cases of tools that no one knows how to use anymore. A repaired ax is a living tradition.”

Our arcade games are wonderful examples of living traditions (to use Mansfield’s term), and so we approach their conservation in the same philosophical way. We haven’t replaced the CRT in our Pac-Man yet, and perhaps we never will, but the key principle is to preserve these incredible machines, as ethically as we can, as living traditions.

After all, we want our guests to be able to play these games not just once or twice but again and again and again.