Reading reports about some retail store closings, it’s hard to ignore that many of us often prefer shopping online with millions of products at our fingertips to navigating a shopping cart through the aisles of our local retailers. As a historian with an interest in consumer culture and as someone who spent countless hours of my childhood playing the latest Nintendo Entertainment System games on a demonstration kiosk at our local K-Mart, it’s difficult to image a world without the striking visual displays and merchandising that have played such an important role in selling products in retail settings. Before the 1880s, few businesses arranged products or store spaces to appeal to shoppers. By the early 20th century, however, following the lead of Philadelphia merchant John Wannamaker and other merchandising pioneers, retailers of all kinds re-decorated their stores using glass cases, mirrors, color schemes, better lighting, interior displays, and show windows to entice their customers. And these displays have been part of retail settings ever since. Not surprisingly, visual merchandising (or the presentation of goods and products in order to attract customers) played an important role in selling home video games from the beginning.

Reading reports about some retail store closings, it’s hard to ignore that many of us often prefer shopping online with millions of products at our fingertips to navigating a shopping cart through the aisles of our local retailers. As a historian with an interest in consumer culture and as someone who spent countless hours of my childhood playing the latest Nintendo Entertainment System games on a demonstration kiosk at our local K-Mart, it’s difficult to image a world without the striking visual displays and merchandising that have played such an important role in selling products in retail settings. Before the 1880s, few businesses arranged products or store spaces to appeal to shoppers. By the early 20th century, however, following the lead of Philadelphia merchant John Wannamaker and other merchandising pioneers, retailers of all kinds re-decorated their stores using glass cases, mirrors, color schemes, better lighting, interior displays, and show windows to entice their customers. And these displays have been part of retail settings ever since. Not surprisingly, visual merchandising (or the presentation of goods and products in order to attract customers) played an important role in selling home video games from the beginning.

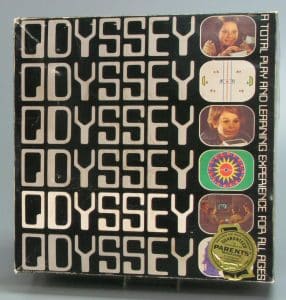

In 1972, more than 60 million American households owned television sets, but few people conceived of television as anything other than passive entertainment. Consumers knew what it was like to watch a TV, but few could even conceive of the idea of playing a TV. Inventor Ralph Baer’s novel idea of using a home television to play an interactive “video game” needed further explanation and demonstration. The Strong’s International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) recently acquired a rare example of an artifact that shows how companies did this.

This item is the first in-store video game merchandising display unit—a Magnavox Mini-Theater and the accompanying five-minute promotional film (digitized by ICHEG) demonstrating the first home video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey. Magnavox stores, dealers, and salespeople used this point-of-purchase merchandising unit and film not only to sell the Odyssey, but also to market home video games to the American public.

The unit’s accompanying 8mm film presented the Odyssey as revolutionary by depicting the transformation of a middle-class American family’s passive television watching into an interactive, fun family experience. As the film’s voiceover explained, “Families content to let television do its thing often find themselves at its mercy for a choice of entertainment, while people who want television to do their thing, entertain themselves with Odyssey.” The film positioned the Odyssey as the “electronic game of the future,” while it also offered a range of practical instructions, such as attaching the console to any brand television between 18 and 25 inches in size, inserting a “game card” into the “master unit,” pressing a special overlay into place on a television screen, using the “player control units,” and playing an “exciting fast-paced tennis game.” For consumers who’d never imagined playing with their televisions, the display unit’s film illustrated how to easily integrate video games into family life.

As video games took hold in American culture, companies did less explaining and more showing off. By the 1980s and 1990s, most toy and department stores featured attractive video game merchandising displays. Game manufacturers such as Atari, Nintendo, and Sega used interactive merchandising displays to introduce new consoles and games and win over potential customers in a competitive marketplace. These interactive displays often gave consumers opportunities to play a new console and some of its best games before players purchased them. In the late 1980s, Nintendo expanded the untapped potential of video game visual merchandising displays with “The World of Nintendo,” a store-within-a-store that promoted the Nintendo product line with logo signage, banners, software and hardware displays, and game demonstration modules. As a 1988 Nintendo Merchandising Program pamphlet housed in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play claimed, “It’s a cosmic fact: 70% of all retail sales result from in-store decisions based on a product’s visual appeal.” Whether or not that is a “cosmic fact,” merchandising displays became important sites for first introducing and then selling video games to the public.

Today, consumers can still play the latest home game consoles on demonstration units in merchandising displays at many retail and toy stores, though the displays are modest in size compared to the large setups of the past. But as more and more consumers buy their games online in digital formats, sooner or later, the visual merchandising and game demonstration units in “brick and mortar” retail stores may disappear. The Strong collects and preserves company merchandising documentation, handbooks, photographs, and demonstration units because the museum recognizes the significant role retail display has had in the history of electronic games. That is why ICHEG is especially proud to preserve an example of the first merchandising display unit and film to promote video games.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.