A proverb in the Bible states, “A merry heart doeth good like a medicine: but a broken spirit drieth the bones.”

There’s sound wisdom in this, as anyone knows who has felt better after laughing uproariously at a silly pet video. Play is not necessarily a panacea, but it is good medicine, a way of introducing fun into life and making it a little more bearable along the way. Because of these beneficial qualities of play, it is not surprising that over the years numerous people have invented toys, dolls, board games, and video games to help patients deal with illness better.

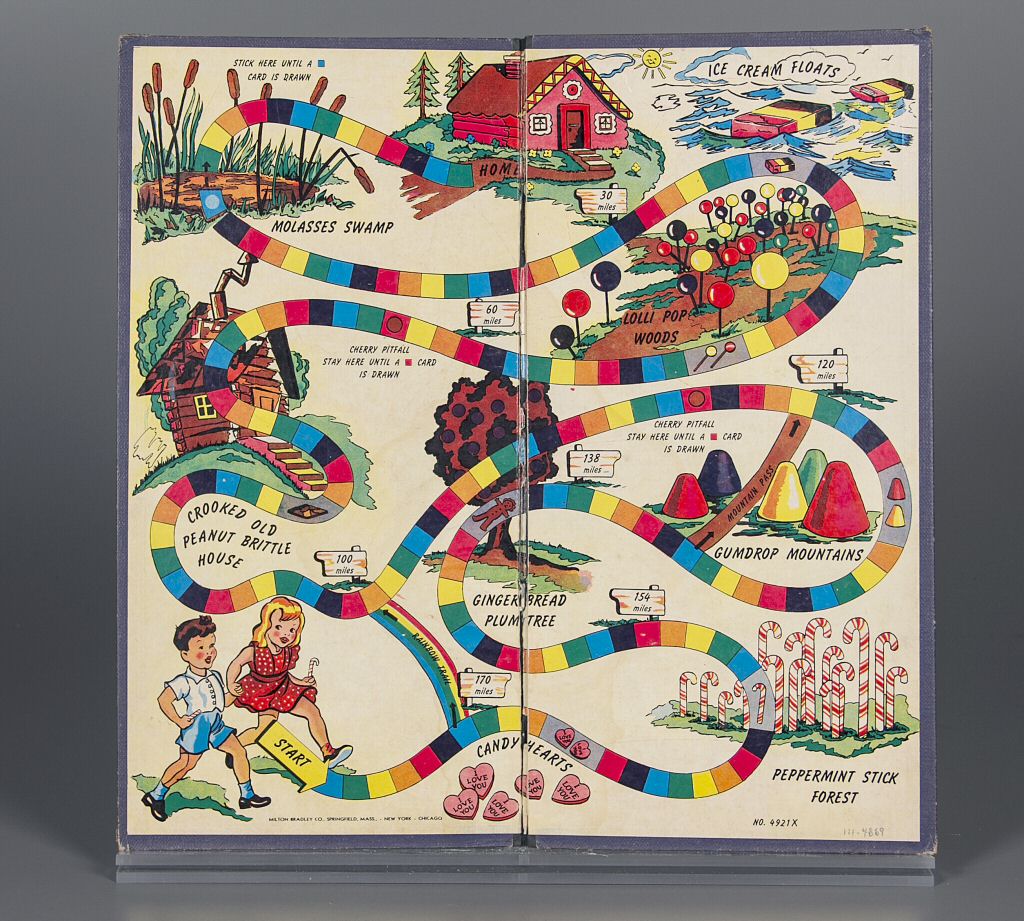

Perhaps the most famous—and successful—commercial product is Candy Land, created in 1948 by Eleanor Abbott to help children with polio. Abbott, who was recovering from polio herself, created the game to comfort children in polio wards. Fears about polio were rising throughout America at the time, in part because a baby boom had dramatically increased the number of children potentially susceptible to the disease. The game’s origin as a salve for children battling polio is reflected in its design elements, as Samira Kawash points out in an essay on its history. The game’s premise of children wandering through a forest without their parents harkens back not only to older tales like Hansel and Gretel but also to the fact that at the time most children battling polio were in institutions separated from their parents. The game’s early iconography also referenced the dread disease. In the first printing of the game the boy in the lower left hand corner seems to have a leg supported by a brace. Interestingly, as the scholar Cindy Dell Clark has noted in her book In Sickness and in Play, Candy Land has sometimes become a favorite of diabetic children, for whom sweets are often forbidden territory.

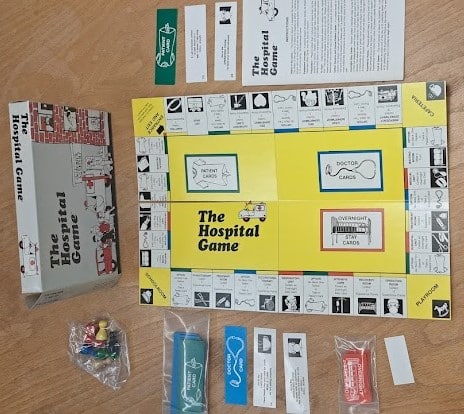

The desire to help children going through hospitalization has prompted the creation of other board games targeted not so much as distraction as explanation. An example of this is The Hospital Game, developed in the 1970s by Elizabeth Crocker who worked with designer James Johnson to make a Monopoly-style game that helped children prepare for a visit to the hospital by exposing them to the x-ray department, surgical unit, and other places in the hospital they would visit and undergo procedures, such as having a cast put on a broken leg. I learned about the game after consulting a 1986 book in our library, Medically-oriented Play for Children in Health Care: The Issues, and seeing a reference to the game. We didn’t have the game in our collection, so I reached out to Elizabeth Crocker and she very kindly donated a copy.

Administrators in hospitals recognized the palliative benefits of play, especially for children, so many institutions began introducing play-based programs for their patients. A search of play scholar Doris Bergen’s papers in our archives revealed, for example, that in the 1970s she had helped organize a play program in the pediatric ward of Pontiac General Hospital in Michigan with two main goals: child play and parent education. The program provided an array of resources, from a playroom to a toy cart that could be wheeled to patients’ bedsides.

The rise of video games introduced a new tool to entertain sick kids and help them pass the time, and perhaps no company has collaborated with health-care providers so consistently here in the United States as Nintendo. Nintendo initiated its efforts with its hands-free controller for the Nintendo Entertainment System. In this adaptive device, created in consultation with eight-year-old Todd Stabelfeldt, who was paralyzed from the neck down, Nintendo allowed users to control characters through chin motions up and down and by puffing and sipping on a tube. “Now everyone can play with power,” exclaimed the controller’s manual.

In the early 1990s, Nintendo rolled out a more institutional approach with its Nintendo Fun Centers. These entertainment stations came equipped with a VHS and a Super Nintendo Entertainment System that sat on a cantilevered arm that easily slid over a patient’s bed. Nintendo partnered with the Starlight Foundation, a charity focused on bringing joy to sick kids, to distribute them to hospitals around the country. Healthcare administrators, physicians, nurses, parents, and kids raved about them, and eventually the program spread to hospitals internationally.

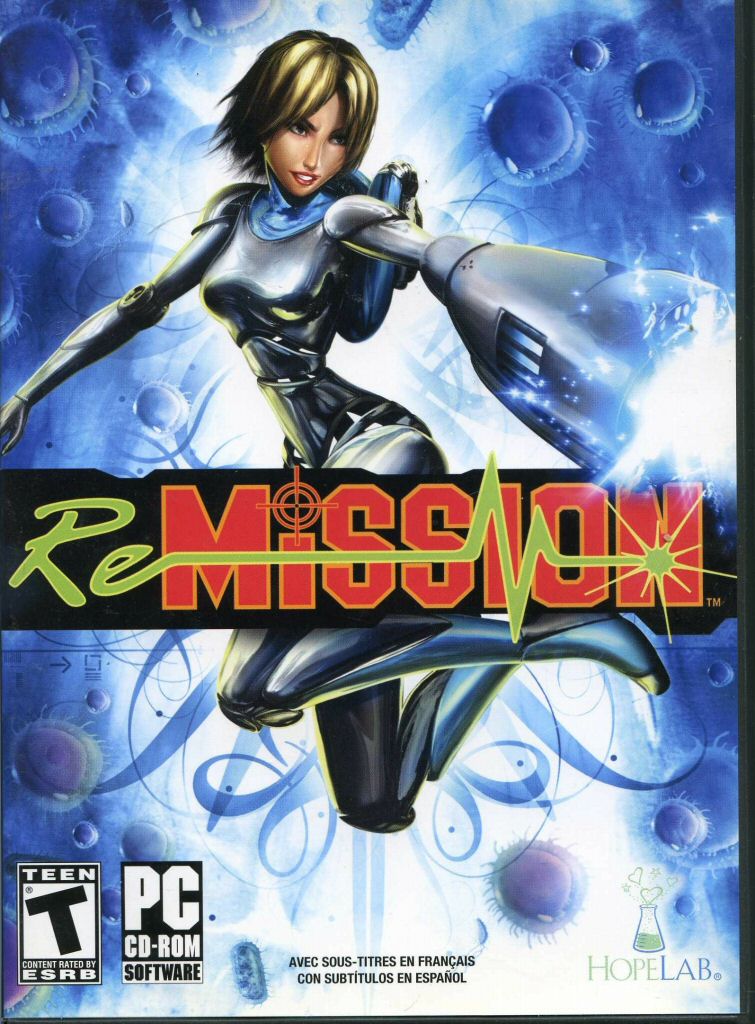

In the 2000s, a variety of programs explored how computer games might help improve patient outcomes. Perhaps the most serious organization to do so was HopeLab, an organization founded by Pam Omidyar whose first product was Re-Mission, a game designed to help kids fight cancer, both metaphorically and literally. Cancer provided the inspiration for the villains in the game, malignant cells that players had to blast. But the purpose of the game was not merely cathartic, it was also designed to encourage patients to better stick with the arduous regimens that are often the byproduct of cancer therapy. By helping children understand how the chemotherapy chemicals in their body were helping them fight the disease, the game encouraged them to keep going. HopeLab did a variety of studies of the game’s effectiveness and found it helped patients stick with their treatments—follow up studies using fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) machines demonstrated that the excited states of players while battling their enemies helped them better remember why the treatments were necessary.

Games, of course, are not the only playthings that have helped kids endure medical treatments or taught them to understand what is happening in a scary place like a hospital. Plush animals and dolls, for example, have been consistent comforts to children for decades. Clowns like Dr. Patch Adams (made famous in a Robin Williams movie) operate in the grim halls of hospitals to bring a little joy to the patients who are enduring the worst moments of their lives. Why do they do it? Because play is vitally important, in sickness and in health.

Dr. Bowen White many years ago began dressing and acting as a clown: Dr. Jerko. In an interview with The Strong’s American Journal of Play, White offered some sound advice for helping people who are sick:

There’s another way to be with people who are suffering. Be light, buoyant, and playful. Play is a way of connecting with people where they are. It’s a way to be both spontaneous and vulnerable at the same time. Without knowing what’s the perfect thing to say or do is, one enters into a psychological space with another person or group of people where the reality of their situation is confronted.

Be light, buoyant, and playful as a way to connect with others who are hurting—that’s a prescription that we could all probably benefit from taking.