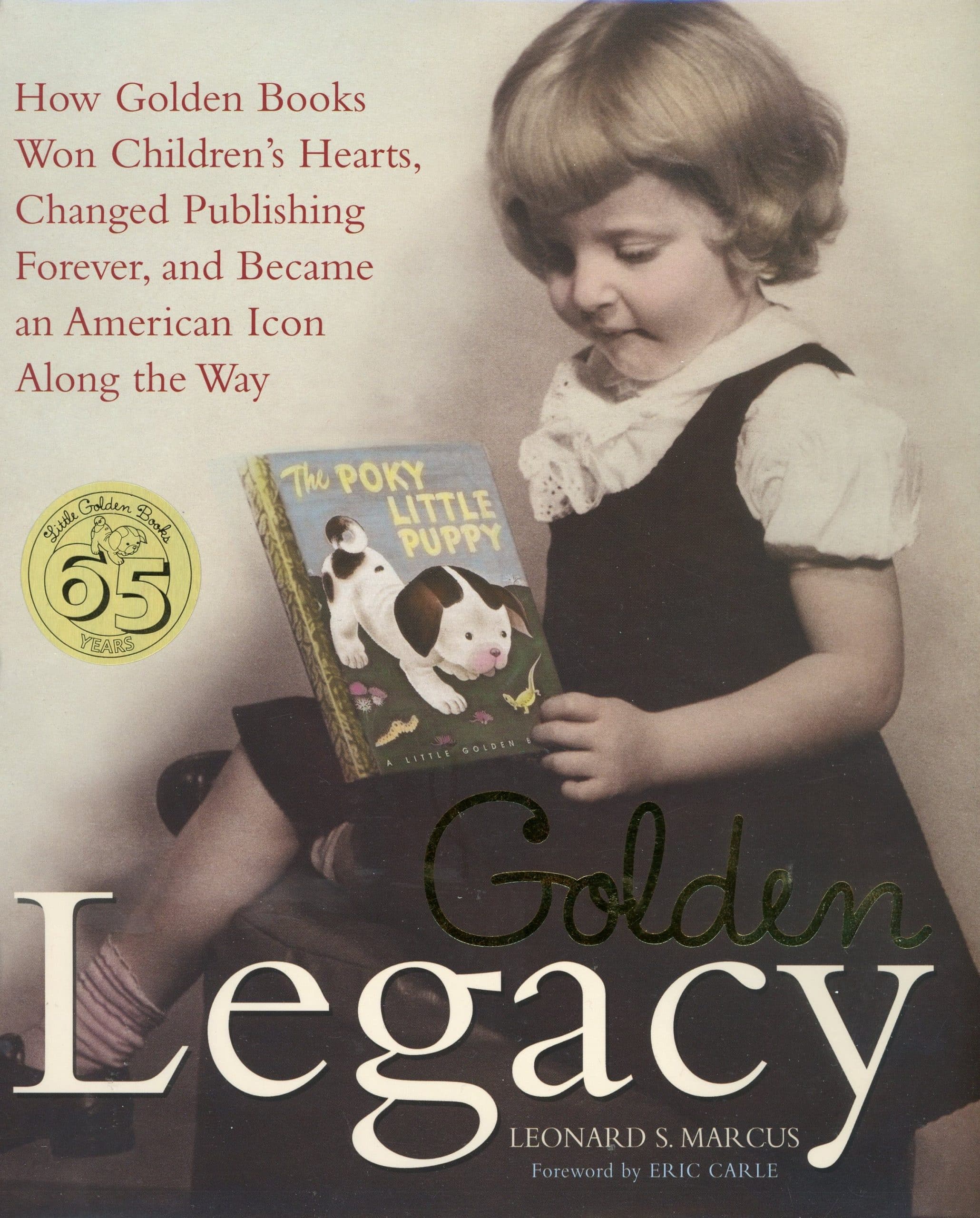

Simon and Schuster published the first Little Golden Books in 1942. Filled with colorful illustrations and appealing tales, these inexpensive picture books hooked kids across America. Thanks to my cousin’s hand-me-downs, my childhood library contained a copy of the series’ Little Red Riding Hood. I confess, I forgot about this book until I began to work on a new display of Little Golden Books for Reading Adventureland at the National Museum of Play at The Strong.

From a ravenous wolf that swallows a little girl whole to a lumberjack who cuts the wolf open, many versions of Little Red Riding Hood contain literary and visual images that leave readers unsettled. One tale of a controversial Little Red Riding Hood illustration begins with Little Golden Book’s editor Lucille Olge’s pursuit of illustrator and Caldecott Medalist Elizabeth Orton Jones during an American Library Association Annual Conference in the 1940s. Each morning during breakfast at the upscale Waldorf-Astoria, Jones found a note from Olge on her silver breakfast tray. Charmed by the editor’s compliments and persistence, Jones agreed to meet and, before the conference ended, she signed on to illustrate a Little Golden Book title of her choosing. In 1949, Olge published Little Red Riding Hood with the resulting pictures. As with most tales about Red Riding Hood, this one contains a twist. In Jones’ final illustration, Little Red Riding Hood (a small girl with blonde braids and a blue dress) held up a tiny tasting glass of red wine. Soon, Olge received hundreds of letters from outraged members of The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Despite the furor, the illustration remained.

From a ravenous wolf that swallows a little girl whole to a lumberjack who cuts the wolf open, many versions of Little Red Riding Hood contain literary and visual images that leave readers unsettled. One tale of a controversial Little Red Riding Hood illustration begins with Little Golden Book’s editor Lucille Olge’s pursuit of illustrator and Caldecott Medalist Elizabeth Orton Jones during an American Library Association Annual Conference in the 1940s. Each morning during breakfast at the upscale Waldorf-Astoria, Jones found a note from Olge on her silver breakfast tray. Charmed by the editor’s compliments and persistence, Jones agreed to meet and, before the conference ended, she signed on to illustrate a Little Golden Book title of her choosing. In 1949, Olge published Little Red Riding Hood with the resulting pictures. As with most tales about Red Riding Hood, this one contains a twist. In Jones’ final illustration, Little Red Riding Hood (a small girl with blonde braids and a blue dress) held up a tiny tasting glass of red wine. Soon, Olge received hundreds of letters from outraged members of The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Despite the furor, the illustration remained.

The Little Golden Book copy of Little Red Riding Hood in The Strong’s collections reveals another concern—that of the ravenous wolf. The controversial image of Little Red Riding Hood with her wine remains untouched. However, the adjacent text displays edits of an apprehensive guardian. The grandmother who gifted this copy to her grandchildren took it upon herself to cross out with black ink any word that might scare the young readers. Thus, when Little Red Riding Hood comments on the wolf’s large eyes, the text reads, “‘The better to see you with, my dear,’ said the wolf, snapping his jaws.” And when she comments on his large teeth, he says, “‘The better to EAT you with!’ And then the wolf sprang from his bed and ate Little Red Riding Hood up….” And did what, I wonder? It’s not uncommon for adults to bark at any tale that might glorify violence, celebrate cunning, and inflame imaginations. I imagine that Grandma enjoyed filling in the blanks.

When I asked colleagues and friends about their impressions of Little Golden Books’ Little Red Riding Hood, they responded, “I never noticed the wine glass,” but, “I adored the illustrations,” or “I prefer the Brothers Grimm version.” Working with the nearly 2,400 titles in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play collection led me to appreciate the moral values that Little Golden Books reflect, but I could also see how they relate to gender, art, political and economical contingencies, and the publishing industry. Next time you visit the National Museum of Play, I hope you check out Big Ideas: Little Golden Books on the ramp in Reading Adventureland.

When I asked colleagues and friends about their impressions of Little Golden Books’ Little Red Riding Hood, they responded, “I never noticed the wine glass,” but, “I adored the illustrations,” or “I prefer the Brothers Grimm version.” Working with the nearly 2,400 titles in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play collection led me to appreciate the moral values that Little Golden Books reflect, but I could also see how they relate to gender, art, political and economical contingencies, and the publishing industry. Next time you visit the National Museum of Play, I hope you check out Big Ideas: Little Golden Books on the ramp in Reading Adventureland.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.