By Adam Nedeff, researcher for the National Archives of Game Show History

“We surveyed 100 people. The top six answers are on the board…”

You probably easily guessed those iconic lines come from Family Feud. But have you ever wondered who those 100 people are?

Writing material and building each episode is plenty of work for any game show. When Family Feud started production in 1976, the staff took on an even bigger challenge. Not only would they write the material (the questions), but they would also collect answers from scores of people, tabulate the results, figure out what would and would not play as entertainment, and then build each show. Here’s how they did it…

In the weeks leading up to the first tapings, when surveys had to be taken for the earliest episodes of a not-yet-seen game, the survey respondents were audience members for other game shows from Mark Goodson-Bill Todman Productions. Studio audience members at Match Game, The Price is Right, and To Tell the Truth would be given pencils and asked to fill in their answers to the list of questions that they were given.

The system worked pretty well. The show was able to avoid “regional bias,” which can affect polling results. For example, if a national survey asks people to name a fast-food restaurant, but a disproportionate number of respondents are from southern California, “In-N-Out Burger” might end up being a very popular answer, even though the regional chain is unknown in most of the country. Fortunately, people who attend TV tapings in Los Angeles were rarely residents. They were usually tourists from all over the country. So, no regional bias.

Once production started on Family Feud, the staff needed to build a mailing list to collect survey responses, but they were uncertain whether the idea would produce the responses they needed. For the first few weeks of Family Feud on ABC, episodes included an announcement giving an address for viewers to write to if they wanted to fill out the surveys that would be used in the game.

The response was tremendous. Thousands of people wrote in to be one of the 100 people surveyed.

With so many eager volunteers, the show figured out how to use the help most effectively. They divided a map of the USA into four sections. To prevent the regional bias, every survey they mailed out was sent to an equal number of people living in each section. Each week, the staff prepared a list of 50 new questions. Those 50 questions would be mailed out to a total of 200—not 100—people.

Producer Cathy Hughart Dawson (host Richard’s former daughter-in-law) explains, “Sending out 200 surveys was a way to guarantee that we’d get 100 responses. If we just sent out 100, we might not hear back from everybody.”

The surveys were opened in the order that they were returned to the office until 100 surveys had been collected. Next, a staff member called a tabulator would gather the 100 answers given for every question. The tabulator was not allowed to editorialize or make judgment calls—instead, they simply counted the results, word-for-word, letter-for-letter, exactly as each respondent had written them.

The questions and the tabulated answers were then passed along to Cathy Hughart Dawson. She would pore through the individual answers and combine answers that expressed similar ideas. For example, let’s say a question was “Name something you buy at a pawn shop.” If 11 people wrote “jewelry,” 9 people wrote “necklace,” 6 people wrote “earrings,” and 5 people wrote “bracelet,” she might combine those answers to show that 31 people said “jewelry.”

As Feud viewers know, an answer not said by anybody in the survey group gets a “strike” in the main game, or a big fat zero in the scorekeeping in the Fast Money bonus round. But even answers given by multiple people could end up on the chopping block.

Cathy Hughart Dawson explains the logic, and the process. “For the Fast Money round, we want the contestants to have every opportunity, so every answer that was said by at least two people counted if the contestants said those answers. For the main part of the game, here’s what sometimes happened. We would get questions with a long list of answers given by two or more people. It would just work out that once I had combined all the similar answers, it would still be something like 15 answers that had been said by two or more people. Playing a round with 15 answers would mean it would take a prohibitively long time to play. When that happened, I would make a judgment call about how many answers we wanted on the board.”

The reason the show has the freedom to do that is because of the language used to introduce each question—“We surveyed 100 people, the top 6 answers are on the board…” Five people may have said a given answer, but if those 5 people were only enough to make it the 7th most common answer in the survey, it’s fine for the show to omit that answer, because they’ve explicitly stated that they want the top six.

The only restrictions that the show had to adhere to in that situation was that they couldn’t skip over answers. If the Feud staff liked a particular answer that was given by 11 people, and they liked one said by 6 people, they couldn’t skip an answer given by 8 people. The answer given by 8 people would have to be included on the show, too.

One quirk of Family Feud—the game is about guessing what many people think, not necessarily what people know. Factually incorrect answers are given the same consideration as correct answers, and an answer that’s somehow “wrong” could appear on the board if enough people said it.

Because the show had so many volunteers (compensated with souvenir bumper stickers and buttons reading “I’m a Family Feud Pollee!”), the 200 people who received a particular survey were moved “to the back of the line” on the mailing list, and another 200 people were mailed the following week’s survey questions.

Volunteering for the show’s surveys didn’t mean you were giving up your chance to win money. People who responded to the surveys were still eligible to be contestants if they could round up four family members to join them as a team. Potential contestants weren’t even asked if they were part of the survey mailing list.

Dawson says, “I don’t think that ever came up, but if it had, I would have felt that there was no conflict of interest or unfairness in having a survey taker be a contestant on the show. We had a massive number of survey takers that we rotated through, and we conducted new surveys every week, so if you were a survey taker and you became a contestant on the show, the odds were already astronomical that you would get a question that you yourself answered. But let’s say you did. You still have to come up with answers that the other 99 people said. And maybe you were the only one to say your answer, which means it’s a strike, so even if you give your own answer, you might hurt your team instead of helping them.”

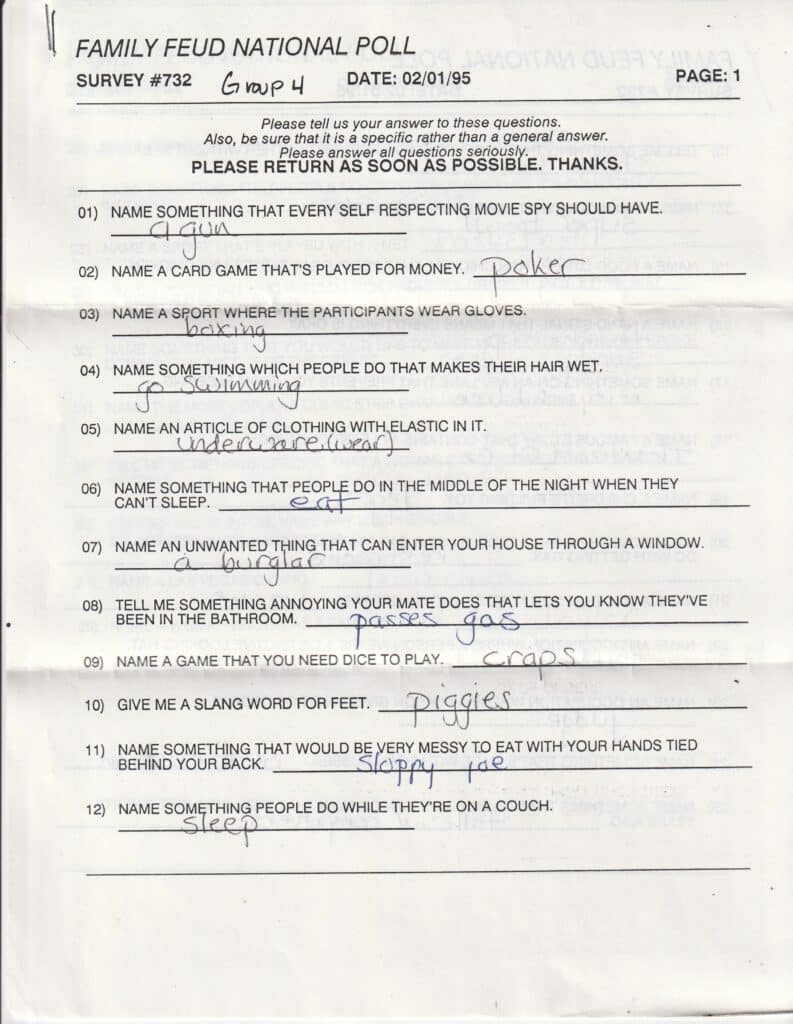

Richard Dawson’s version of Family Feud ended in 1985. When the show was revived in 1988 with new host Ray Combs (until Dawson returned for the 1994-95 season), they continued using the same mailing lists and continued building them the same way. Josh Guers, who supplied the sample surveys seen with this article, wrote to the show for a school project and ended up on the mailing list.

When Family Feud returned in 1999, a third-party company was hired to compile the surveys for the show using methods of their own design. Today, it’s as simple as picking up the phone when it rings. Family Feud starring Steve Harvey has a research firm, Applied Research West, call 100 people on the phone and compiles their answers for many questions used on the current version of the popular series.