Some of my fondest childhood memories date back to the 1970s and 80s when my grandparents would take my sister and me to Friday night bingo at the local fire hall. The moment we stepped into the building, we were enveloped by the sights, sounds, and aromas of bingo. Hot dogs, popcorn, and refreshments were served and lines formed to purchase the requisite bingo cards. Often we sat with my grandparents’ “bingo buddies” at long tables lined with metal folding chairs.

Usually, my sister and I purchased about four heavy card stock boards and a small handful of “specials.” Once seated at the table, our grandmother would pull items out her bingo bag and set up our area. She gave us pennies for the “free space,” plastic chips for the cards, and daubers for the specials. Then she’d pull at least 10 to 15 good luck charms out of her bag, each with special meaning for her, although the carved elephants were her favorite. We assembled the trinkets at the top of each board and tickled our fingers across the tops of them for good luck, a familiar routine for many players.

Excitement peaked when someone from our table won. It was customary for the winner to pass the prize money around for everyone to touch, another ritual for good luck. My grandparents always maintained five times the amount of cards that we had, and they would still manage to find numbers on our boards that we missed. For my sister and me, this wasn’t just Friday night bingo—it was an entire cultural experience, and we loved every minute of it.

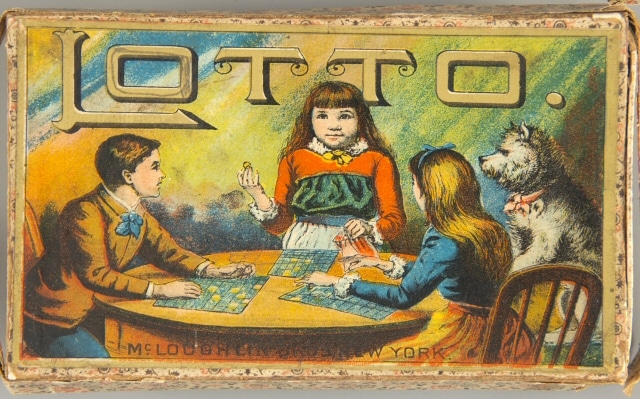

While researching in The Strong’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play, I learned that bingo is a derivation of the game lotto. According to Merilyn Simonds Mohr’s book, The New Games Treasury, lotto, a game of chance, can be traced back to 1530 in Italy where it was known as Lo Giuoco del Lotto de Italia. Unlike bingo boards, lotto boards are rectangular with nine squares across and three squares down for a total of 27 squares per board. By the 19th century, lotto had spread throughout Europe. In addition, spin-off versions stylized with words and pictures were marketed and sold as educational games.

Bingo was popularized in the United States due to the ingenuity of Edwin S. Lowe. In 1929 Lowe, a traveling New York salesman, spotted a carnival as he passed through Georgia. There he noticed a crowded booth where people were playing a game with hand-stamped boards and beans. He learned that the game was called “Beano,” and that the game operator derived the activity from a lotto game that he had played in Europe. Back in New York, Lowe experimented with numerical combinations on the Beano boards and invited his friends to test out the game. As the legend goes, one of his guests mistakenly called out “bingo” instead of “beano” after a winning combination of numbers and the new name stuck.

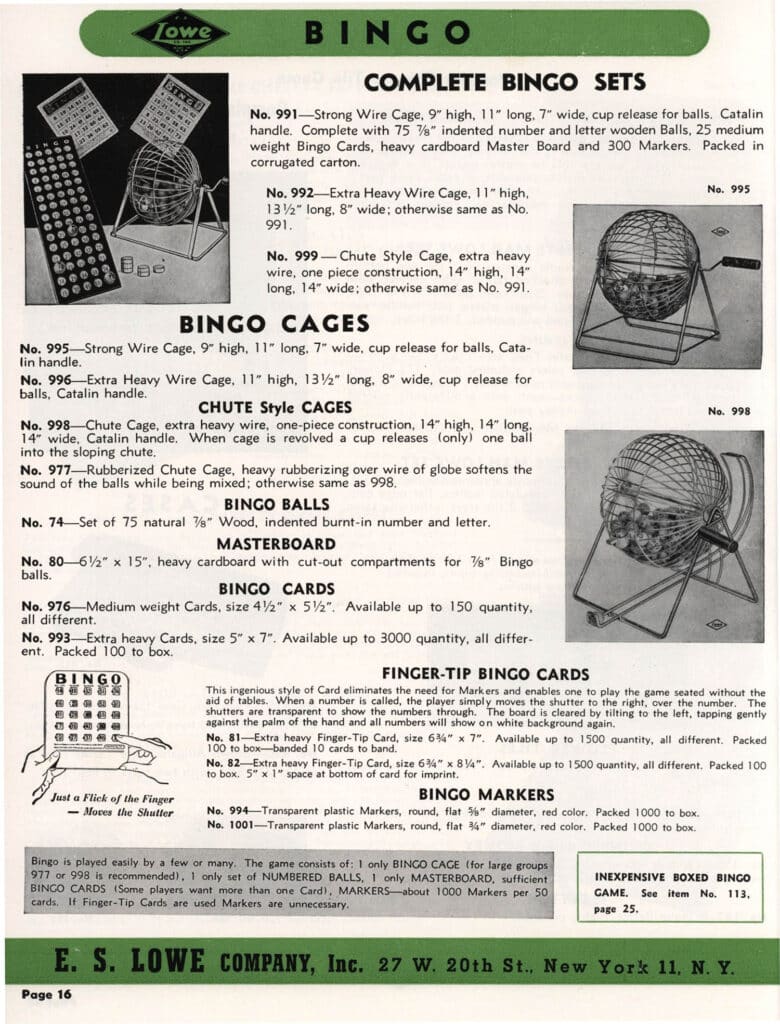

Lowe began manufacturing bingo boards in the early 1930s and hired a retired mathematician to devise more than 6,000 different numeric combinations for the boards. Eventually, bingo developed wide popularity and churches and fraternal organizations purchased sets to use as fundraisers. At the same time, home versions of the game also proliferated and, by the late 1930s, several other companies produced bingo sets.

Bingo remains popular to this day; in many locations the game has even been updated to include electronic boards for players to use. Home versions of bingo are still staples of families that have young children. The Strong has more than 20 different versions of bingo represented in its collection, including a Superman version. In addition, there are more than 50 trade catalogs in the Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play in which bingo sets can be found. It all makes me think that I’m well overdue for playing a couple boards. I may just go back to that fire hall some Friday night, pull out all my good luck charms, and see if I get the chance to yell out “BINGO!”

By Tara Winner, Cataloger

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.

Hours 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Fri. & Sat. till 8 p.m.