By Adam Nedeff, researcher for the National Archives of Game Show History

The most prolific name in the history of game shows was a man who once admitted to TV Guide, “I’m certainly not the man who appeals to women ages 18-35.”

Bill Cullen was right about that. He appealed to everybody. For 40 years, he appeared on one game show or another; often one game show and another. His gigs overlapped and he had no qualms about taking on whatever work he was offered.

Born in Pittsburgh on February 18, 1920, Bill Cullen was stricken by polio as a baby and devoted his youth to conquering it. Despite being slowed down by a prominent limp, he took boxing lessons, he played sandlot ball, and even gave auto racing a try. Once out of high school, he got a job at his father’s garage, repairing engines and driving the tow truck. He would entertain customers by impersonating radio stars while he made his repairs on their car. When a salesman from local radio station WWSW came to the garage one day, Bill’s father talked him into giving the boy a job.

Bill, only nineteen years old, made the most of the opportunity. He secured a commercial endorsement deal for a local business and local newspapers would quote some of the jokes he made on the air. He developed something of a reputation for being WWSW’s on-air class clown. Convinced nobody was listening to the dull records he had to play sometimes, he would play the records backwards or toot a toy whistle. He would give wildly wrong accounts of the game in progress when he called play-by-play for sports, or ignore the game altogether and read the comics to listeners instead. Fearful of falling into a rut, Bill moved to New York City when he was 24 years old to see if he could get hired by one of the major radio networks.

As Bill would modestly point out himself, polio had kept him out of the military with World War II raging, but that prominent limp made him very employable. Many announcers in New York had left their jobs to serve in the military. Bill served as announcer for seven different shows during his first two years at CBS, and supplemented his income as a joke writer.

A fellow joke writer, Bill Todman, was looking to get out of the writing end of show business and focus on show development and production. When Todman and business partner Mark Goodson sold a show, Winner Take All, to CBS, with Bill Cullen as announcer. After only three months, Bill got the promotion to host. He never looked back.

More shows would follow: Catch Me If You Can, Hit the Jackpot, Beat the Clock, Act It Out, Meet Your Match, Quick as a Flash, Fun for All, Professor Yes ‘N No, Walk a Mile, Place the Face, Bank on the Stars, Stop the Music, Name That Tune, Down You Go, The Price is Right, Eye Guess, Three on a Match, Winning Streak, The $25,000 Pyramid, Blankety Blanks, I’ve Got a Secret, How Do You Like Your Eggs?, Pass the Buck, The Love Experts, Chain Reaction, Blockbusters, Child’s Play, Hot Potato, and The Joker’s Wild.

Did you get all that? A total of 29 game shows as permanent host. He also served as guest host for a few other games, Strike It Rich, To Tell the Truth, He Said She Said, and Password Plus. It’s a resume that overshadows even his closest contenders, Wink Martindale (17 game shows) and Tom Kennedy (15 game shows).

Over the years, Bill would talk at length about the skills required for a game show host. His modest attitude betrayed the actual work that he put into it. While he would repeatedly insist it was an easy job, the more he talked about it, the more apparent it was that Bill cared a lot about the art of hosting a game show, and that he put a great deal of thought into it day after day after day.

“Being a master of ceremonies? An easy job. Whenever the networks have a new job, they always complain that all the MCs are working and they can’t find a new one. That’s nonsense—anybody in show business can be an MC. All you need is to be reasonably okay in appearance and to have a good voice. The rest you pick up as you go. The hardest things to learn are pace and anticipation. And the only way to learn them is through experience. You’ll learn how to pace a show so it builds to a climax, and how to anticipate the good things and the possible problems. When you have job security, that helps. If you know you’ll be back on the next day, you don’t have to press so hard. When a contestant says something funny, you don’t have to try to top him.”

“[I am] dependable to a fault, never late, always reasonably amusing without insulting my guests or doing anything to them I wouldn’t want done to myself. The contestants who come into my arena have one shot at it, and I think they should have their day. Me, I’ll be back the next day and the day after that.”

“I know my trade…I absolutely never let anything upset me—on the air, I mean. If an error is made, I figure there’s always tomorrow. I refuse to get aggravated. To me, that’s the secret of my success—no, better say longevity. And it shows. I’m not one for making a big deal of it.”

Bill’s greatest successes were a nine-year tenure as host of The Price is Right; those nine years were contained entirely within his 15-year run as a regular panelist on I’ve Got a Secret. They were, by far, the two most popular game shows on television during Bill’s golden era. At the same time, he was New York City’s #1 disc jockey, dominating drive-time radio for six years.

Bill’s success during those years would either help or hinder him later, depending on how you look at it. His phenomenal success during that period ensured that he could continue working for years afterward, as long as he wanted, and that he’d be handsomely paid for it. But he never hosted another show that achieved the heights of success that he achieved with Price and Secret.

Candidly, it was because in many cases, Bill was being used to prop up weaker games. Bob Stewart was the creator of Eye Guess, the first show Bill hosted post-Price. Stewart bluntly referred to his own creation as “third-rate” and said that the success of the show was entirely thanks to Bill Cullen. Later shows on Bill’s resume would have extraordinarily short runs—Winning Streak in 1974 lasted six months, and Blankety Blanks ran a paltry ten weeks in 1975.

After the cancellation of Blanks, Bill said, “I’ve been fortunate…The passage of shows hasn’t hurt, because I don’t get blamed for it. It does hurt me in another way, though, because I feel a certain amount of responsibility. But you make yourself realize that nothing more can be done about it.”

But to his credit, it was probably because of Bill that those shows got on the air in the first place. He could give extra luster to a rusty concept, and game show director Bruce Burmester theorized that if a viewing audience liked a person on their screen enough, they’d be willing to go along with that person. Bill could win over viewers enough that they’d at least give the show a few chances before switching the channel to something else. Even to the very end of his career, he was more than a bargaining chip for a weak format; he could be salvation. One of his final shows, 1984’s Hot Potato, was pitched to NBC executives, who said that they would specifically buy it if Bill Cullen was hired to host it.

Bill would continue hosting game shows until 1986, at which point he retired without any fanfare and settled for a quiet happy retirement of swimming, reading, and long naps in a big comfy chair. He even did retirement perfectly.

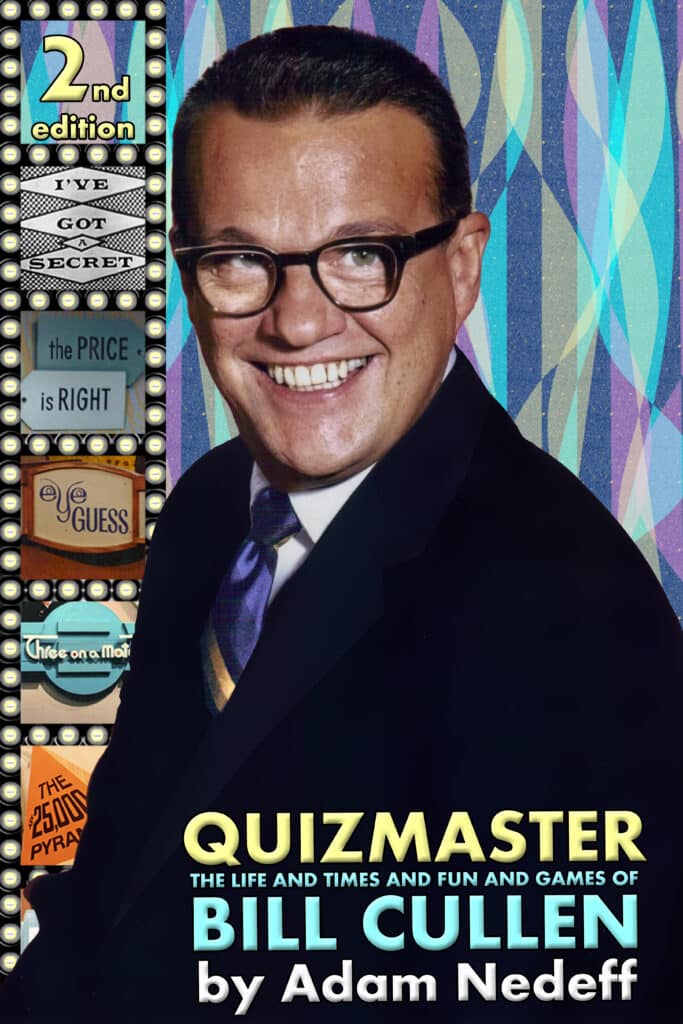

Adam Nedeff is the author of Quizmaster: The Life and Times and Fun and Games of Bill Cullen, published by BearManor Media. The new 2nd edition of the book went on sale on February 18. National Archives of Game Show History co-founders Bob Boden and Howard Blumenthal both provided interviews and research for the book.