In May 2025, I had the pleasure of spending two weeks at The Strong Museum as a Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow to conduct research on the collectible card game (CCG) genre. While the field of Games Studies has grown significantly in the last decade, locating texts, artifacts, and archival materials focused on games and play in most institutional libraries and archives is difficult. Given my own research focus is understudied, even within the field, the problem was compounded for me.

For those who are not familiar with CCGs, this is a genre of card games that emerged in the early 1990s, and encompasses games that are also called trading card games, customizable card games, expandable card games, among others. The general idea behind CCGs is that cards that are used to play the game can also be treated as collectible objects. This is achieved primarily through the use of randomized card distribution in booster packs, similar to how baseball cards are sold. Examples of CCGs you might be familiar with include the Pokémon Trading Card Game and digital games such as Hearthstone.

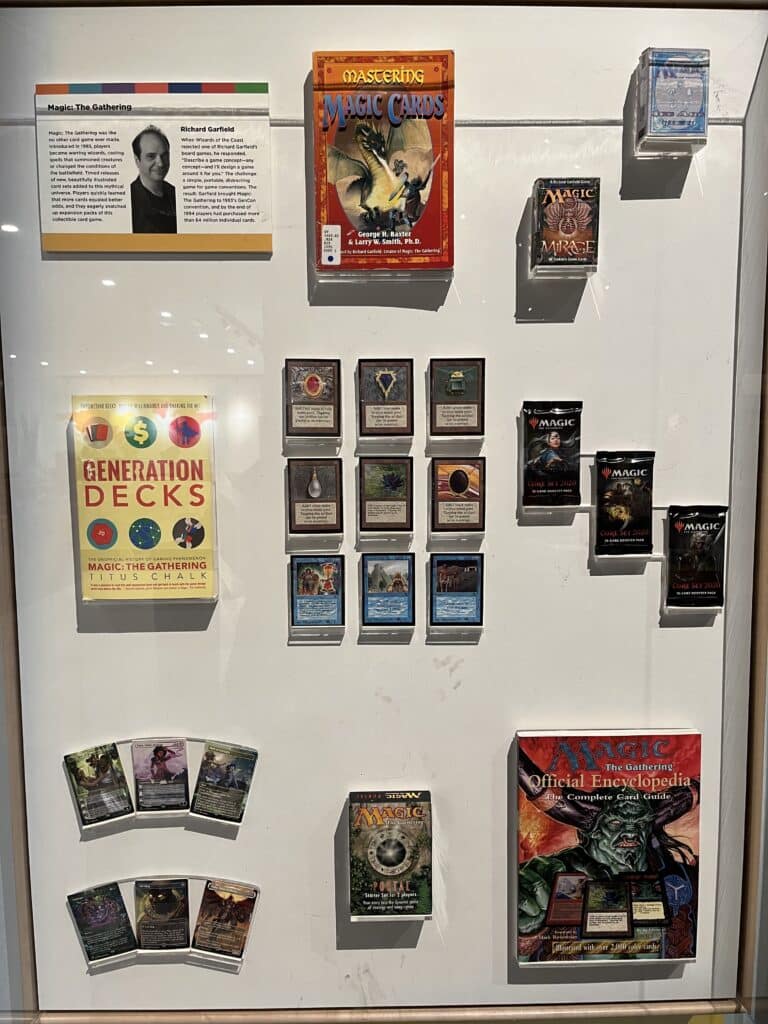

At the museum’s Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archive of Play, I found a wealth of material that directly addressed many of my research questions about the early days of the CCG genre. While the creation and growth of the first CCG, Magic: The Gathering, is well-documented, the months and years after the release of Magic, which saw the rapid growth of the CCG market and industry, has largely remained forgotten. Since the larger goal of my research is to look at the CCG genre broadly, its complete history was something that I felt needed to be recovered.

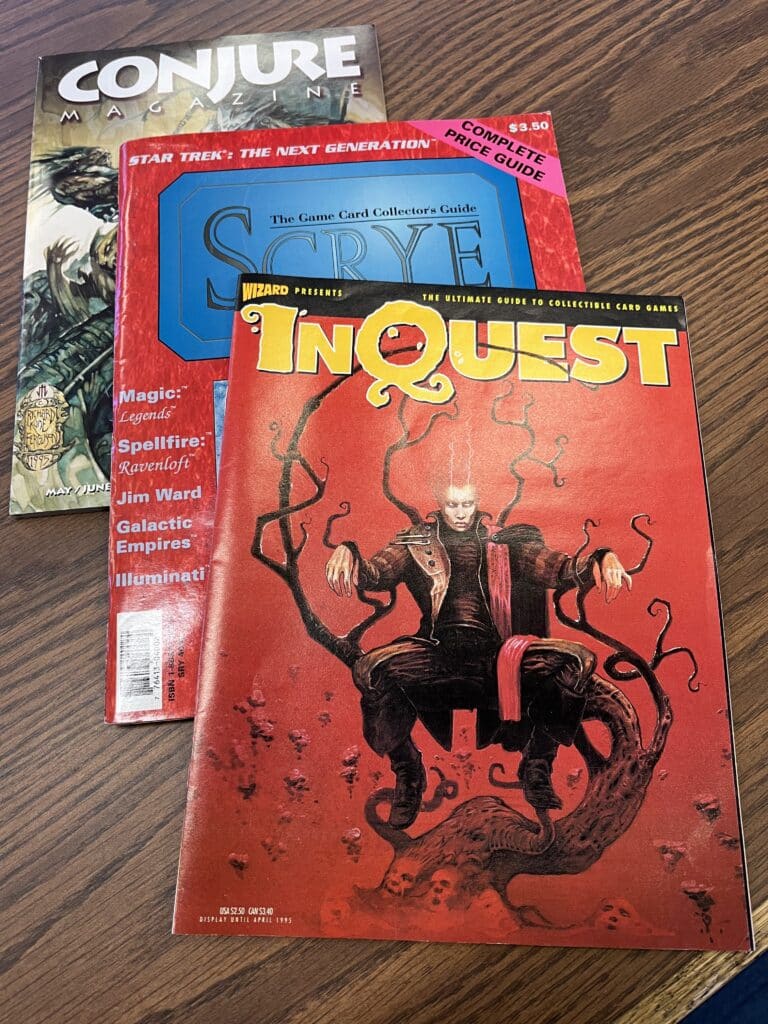

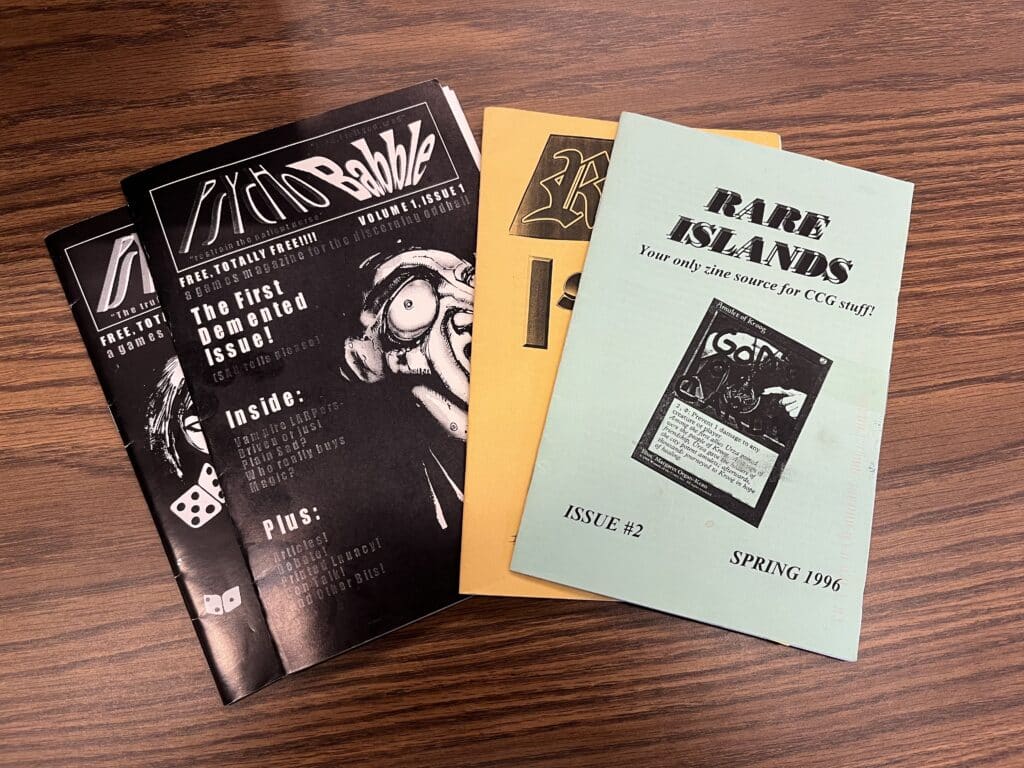

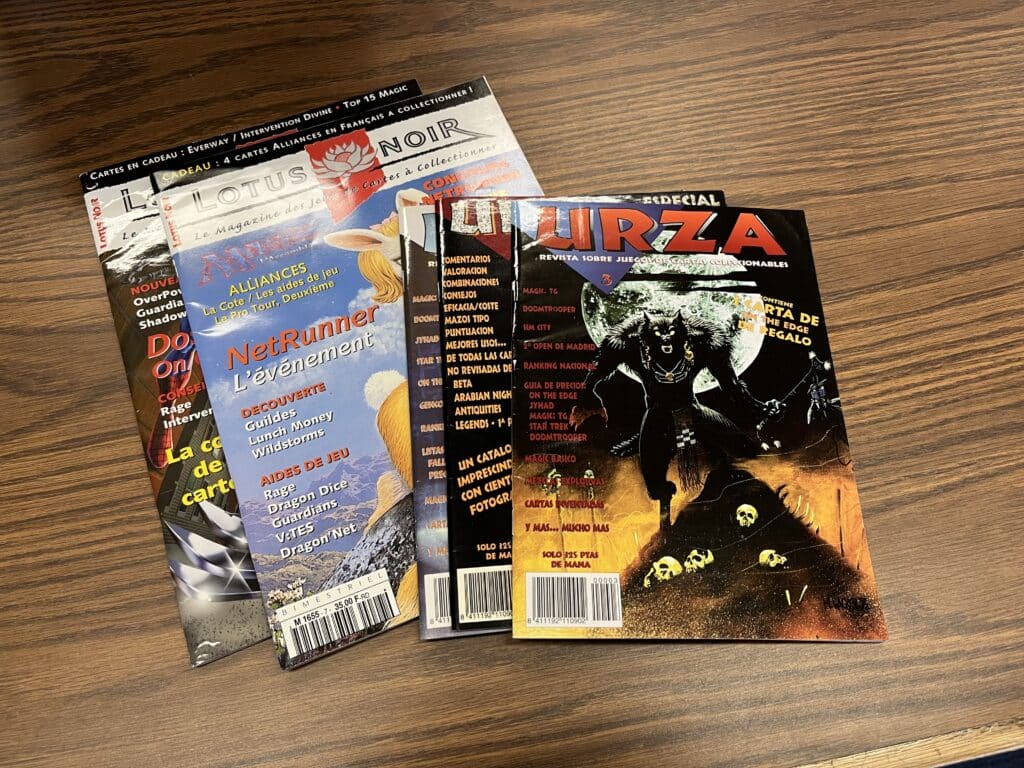

The first things that I sought out at the library were periodicals focused primarily on collectible card games, namely magazines such as The Duelist, Scrye, Conjure, and Inquest. These publications grew out of the CCG boom in the early- to mid-1990s, but eventually disappeared in the 2000s as access to the Internet became more widespread. The Strong has an extensive holding of these publications, as well as foreign language magazines and even smaller publications such as zines. I also found a wealth of trade catalogs and flyers sent out by CCG publishers to distributors and game stores among the library’s holdings.

The other category of material I looked at were archival documents from Mayfair Games, the game publishing company founded by Darwin Bromley. My particular interest in the Mayfair Games archive has to do with the firm’s role as the designer and publisher of SimCity: The Card Game, a CCG adaptation of the very popular computer game created by Will Wright, which was released in 1994.

From examining these materials, here are some of the things that I’ve found that relate directly to my research. The first was the immediate impact on the gaming industry of the 1993 release of the first CCG, Magic: The Gathering. While I have said that the history of the game has been written about, this history is mostly told from the perspective of the publisher and game designer. For players, as well as other game designers and publishers, the weeks and months after the release of Magic were hectic.

Within the Mayfair Games archive, I found printouts of message board posts about Magic from the time. These posts range from reviews of the game, reports from frustrated players about the scarcity of the game in local stores, and posts about the possible financial value of the cards. I also found message board posts from game designers, trying to understand how the game was made in the first place, and how the cards were being distributed randomly.

In the publications that I looked at, that same excitement is palpable in the letters sent in by players. Players wrote in about new or powerful cards they managed to find in packs, or unexpected card interactions that won them a game, or trades they’ve made to get cards they wanted.

One magazine even had a section where game store owners from across the U.S. and Canada wrote in to report about the sales and activity around CCGs. A common thread in these game store owners’ early reports were the huge demand for the game and the very limited supply. Later, when other CCGs began coming out and Magic’s supply had risen to the point that it could fill the demand, the tone of these reports shifted to that of unsold boxes, accompanied by doubt and worry about the future of the market for these games.

The other thing that I found of real import to my research is an insider’s view of how one game company—in this case Mayfair Games—tried to figure out the CCG genre and market. As I mentioned, Mayfair Games published SimCity: The Card Game in 1995 but, as it turns out, they had worked on many other CCGs in the mid-1990s. The company tried to create CCGs based on the Parker Brothers card game Touring, the magazine National Geographic, and their own role-playing game DC Comics Heroes, based on the popular comic book IP.

However, of these many CCGs, Mayfair ended up producing only two, the first of which was SimCity. Mayfair Games had acquired the license to create a card game based on the video game in 1993. Mayfair Games believed that the SimCity CCG would be the game that would appeal, not just to fantasy and science fiction gamers, but to the mass audiences, as well.

The Mayfair Games archive presents the history of the game’s development from its inception to its production, and finally its release and reception. One particularly interesting thing to find in the archive was the inclusion of cities in my home county, the Philippines, on the list of cities the game would have featured if it had achieved the massive success Mayfair Games had hoped it would be. The archival material also outlined the difficulties of producing and releasing the game. This included delays in design and in printing, as well as issues with how stores were allocating shelf space for the game.

The other CCG Mayfair Games produced was called Fantasy Adventures and was released in 1996. Based on a card game the company had published in the 1980s called Encounters, Fantasy Adventures drew heavily from the fantasy genre like Magic and Spellfire, a CCG-based on the seminal tabletop roleplaying game Dungeons & Dragons.

Unlike other CCGs of the time, which utilized original artwork from fantasy artists, Mayfair Games went to seasoned fantasy artists and bought second-rights to their artwork, many of which either appeared in magazines or graced book covers. This was one of the primary selling points of the game—that top-notch artists had created the art on the cards—because the company believed that the success of CCGs could be traced to the artwork on the cards.

The other thing of note about Fantasy Adventure was that, even as the first edition of the game was being developed, Mayfair Games had already begun making deals with video game companies and publishers to create tie-ins.

The biggest of these tie-ins was a set of cards featuring the world of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series, which would be playable with the base game. Jordan himself would be involved in the development of this card set. The Mayfair Games archives includes letters from Jordan himself providing guidance and giving approvals for cards and the artwork that would appear in the cards. The company even tapped into Jordan’s massive fanbase to try and get the flavor of the cards right, by asking them to playtest the cards. Unfortunately, Fantasy Adventures was just one of more than 70 CCGs released in 1996 and, like all of them, the game soon went out of print.

While the study of successful CCGs such as Magic and Pokémon can tell us about what makes the game genre appealing to players and collectors alike, examining the largely forgotten games in the early days of the genre tell us about how the gaming and collectible industries adapted to the emergence of the CCG.

Written by, Francis Paolo Quina, 2025 Valentine-Cosman Research Fellow at The Strong National Museum of Play.