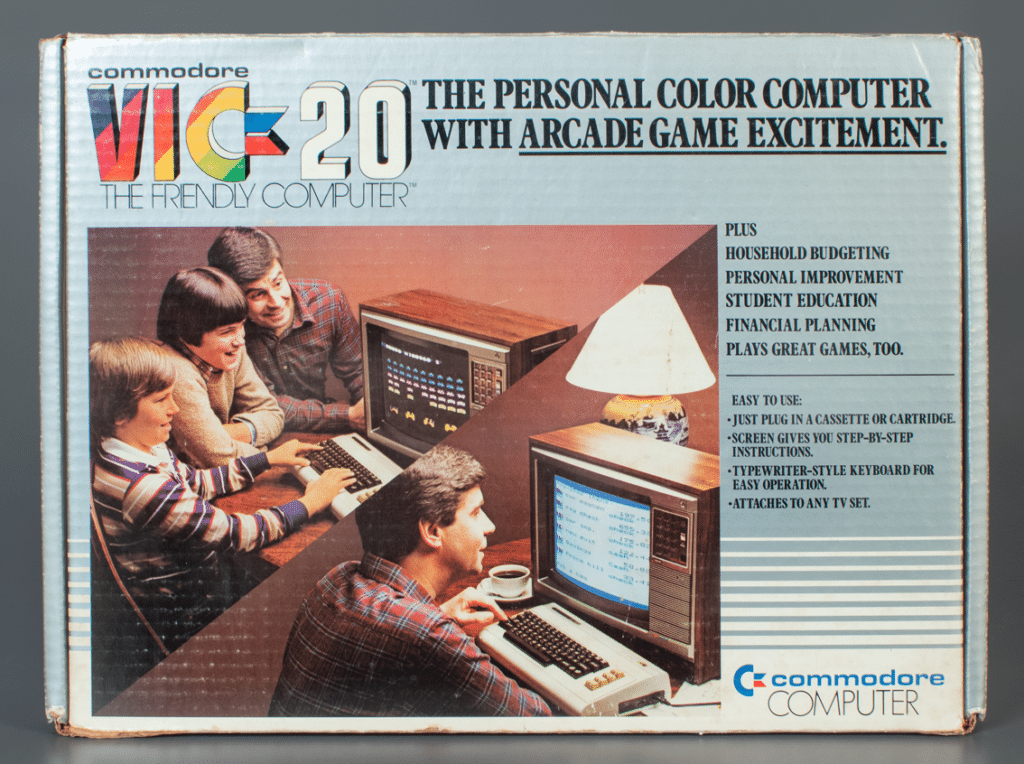

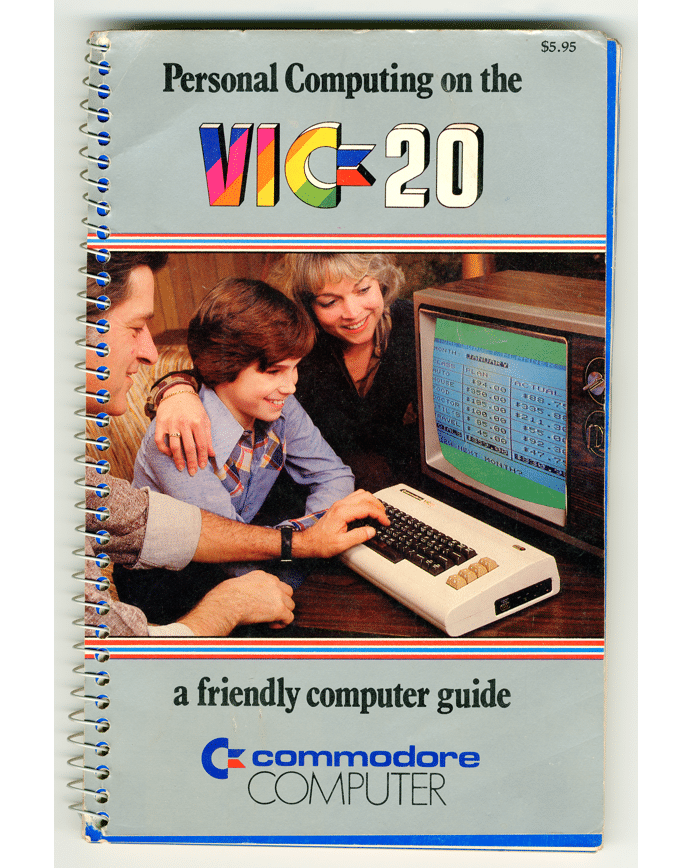

The Commodore VIC-20 first debuted at the Computer Electronics Show held in June of 1980. It began to be sold for North American households the following year and from the get-go was a hit–an inexpensive computer that could display color graphics. The other major competitors of the time were the Atari 400, TRS-80, and Apple II. It’s easy to forget now, but in the early ’80s, Apple was still the newcomer, whereas Commodore—under the leadership of the aggressive and visionary Jack Tramiel—was already a well-established player in the electronics market.

Commodore’s goal was simple, quoted from creator Tramiel himself: “Computers for the masses, not the classes.” Many hobbyists learned how to code on the machine, as it was one of the more affordable 8-bit entry computing systems of its time.

Its low cost and developer-friendly architecture made the VIC-20 popular not just among casual users but also within the growing coder and gamer communities. It went on to become the first personal computer to sell more than one million units—ultimately reaching an impressive 2.5 million over its lifetime.

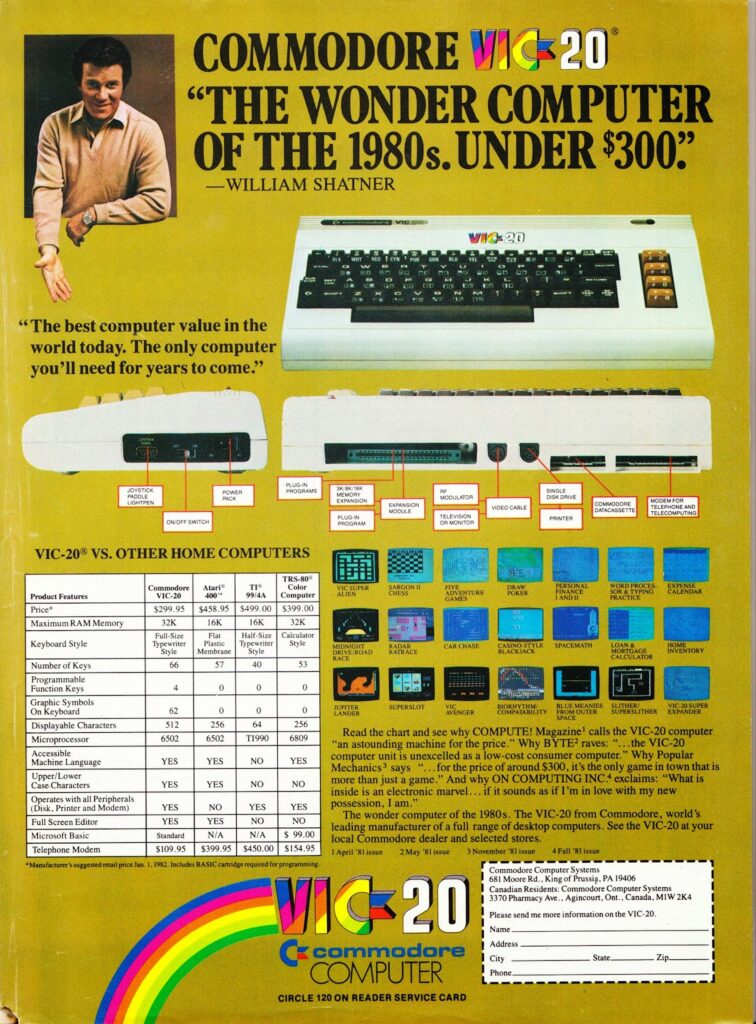

Commodore even brought in celebrity endorsements to promote the VIC-20. William Shatner, of Star Trek fame, starred in television commercials encouraging households to bring home this “wonder computer of the 1980s.”

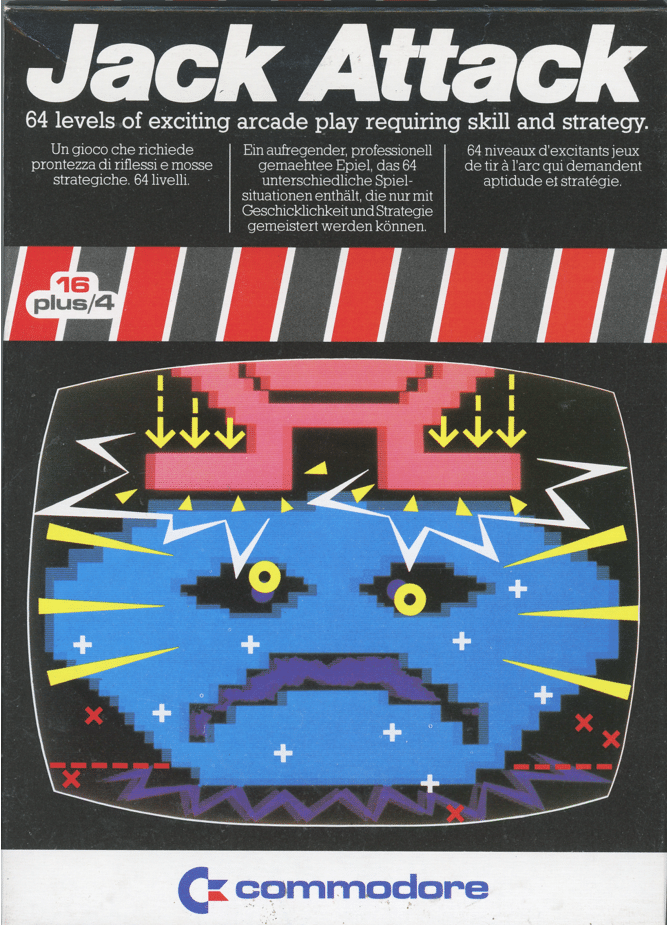

Donations play a vital role in shaping our collections at The Strong Museum. In recent years, both collectors and former developers have generously contributed VIC-20-related artifacts. One such donor is Scott Elder, co-creator of the game development company Nüfekop, who provided a treasure trove of items tied to his company’s history.

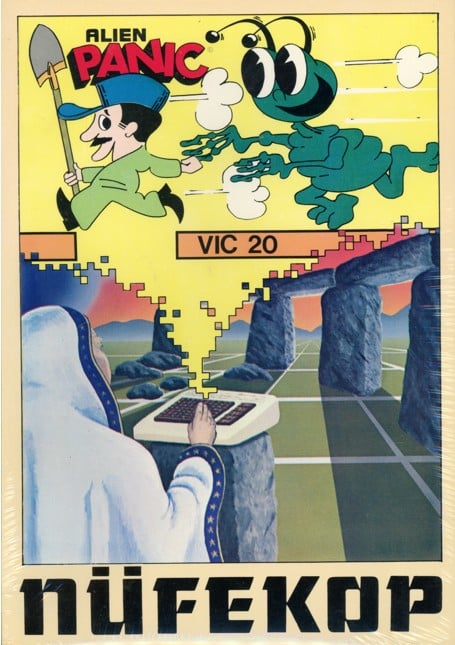

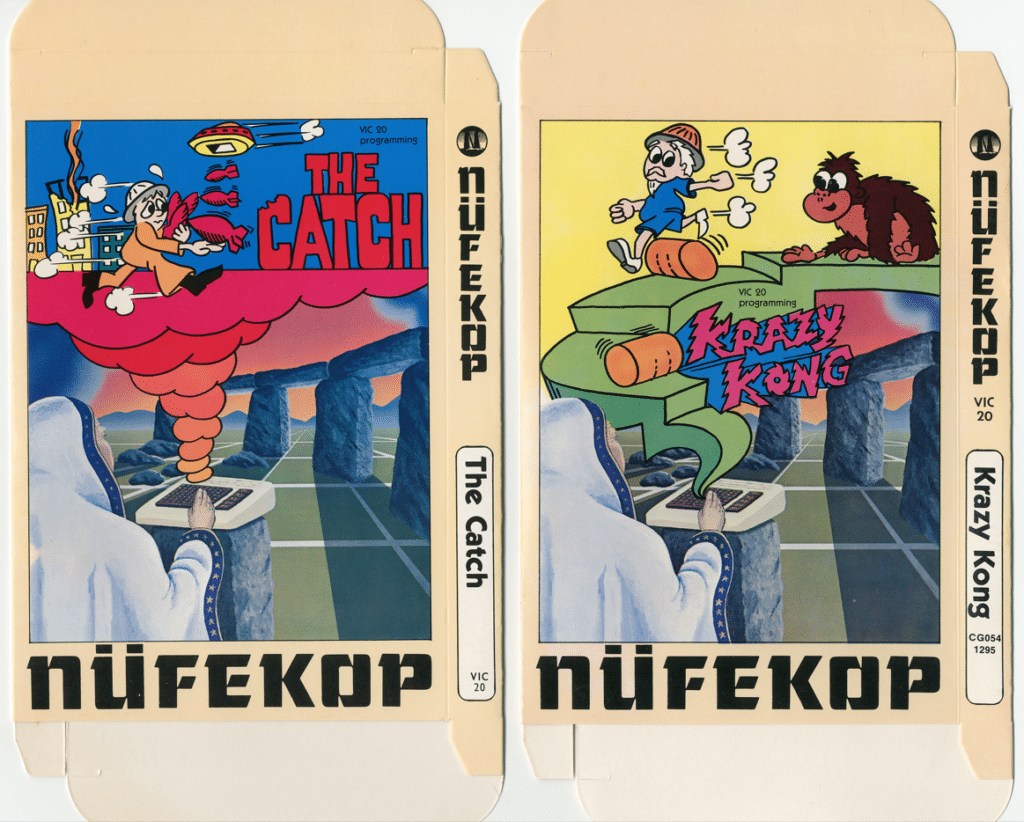

Nüfekop developed and published titles for both the Commodore 64 and the VIC-20. The company name itself has a quirky origin—co-founder Gary Elder invented a fictional “Druid” mythos linking Nüfekop to Stonehenge. Alongside his brother Scott, the two created games from scratch, turning a bedroom project into a full-fledged publishing effort. (Fun fact: try reading the company name backwards.)

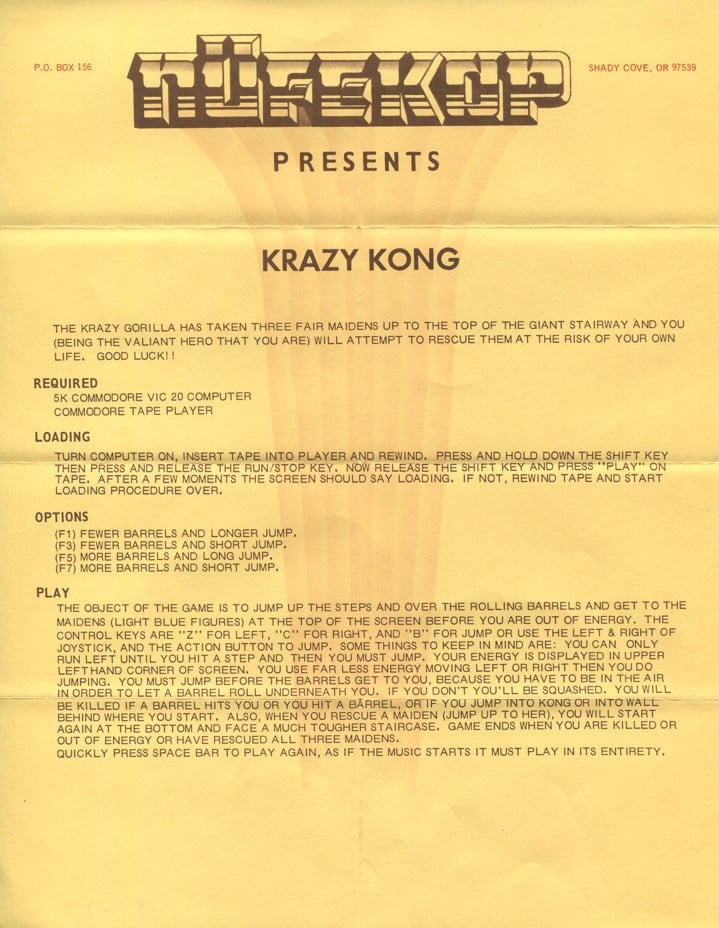

In addition to commercially available games, the donation by Scott Elder also included things that were never released, such as alternative product packaging. Other ephemera donated included posters and advertisements, such as the Krazy Kong advertisement as seen above.

The Commodore VIC-20 holds a special place in the history of personal computing—not just as a bestselling machine, but as a gateway that introduced millions to the world of digital creativity and play. Its affordability, accessibility, and wide game library helped pave the way for the home computing boom of the 1980s. More than just a piece of hardware, the VIC-20 became a platform for innovation, where garage developers could become game creators and everyday users could become programmers.