Back in 2019, Dr. Sami Schalk contributed a piece to Inside Higher Ed titled “Lowbrow Culture and Guilty Pleasures? The Performance and Harm of Academic Elitism.” The article was in response to Times Higher Education reporter Jack Grove’s tweet, which put out a call to “some scholars who would write for THE about their guilty cultural pleasures/unashamed love for supposedly ‘lowbrow‘ subjects/activities.” Dr. Schalk argued that the uncritical use of term “lowbrow” ignored the biases embedded in such a word, as did the term “guilty pleasure.” Instead, Dr. Schalk reframed the question as “what is something you love that society tells us is not valuable, intelligent, or cultured?” This question resonated with me on many levels. It’s also a topic that I think about when I look at playthings. Some of the toys and dolls I treasure the most are inexpensive, dime store novelties or pieces considered “lowbrow” by the mainstream. A recent donation from a collector researching gross-out toys from the 1980s and 1990s had many examples of tacky and wacky things, including hundreds of trading cards from The Topps Company. These cards are not just collectibles that cause some to repulse, but also provide a unique perspective on consumer culture, play, and censorship.

To fully understand the significance of The Topps Company’s trading cards, I think we need to go back to the 1950s. In 1954, the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers put together the Comics Code Authority. The code included a crackdown on sexually explicit images, werewolves, zombies, and ghouls, violence, drugs, and vulgar language. It also implied that criminals could not triumph over good and authority figures must be respected, as should the sanctity of the family (no divorce, for example). Comics that met the 41 restrictions carried the official seal of approval. Many scholars credit Dr. Fredric Wertham as the reason for these guidelines. In his book, Seduction of the Innocent, Dr. Wertham correlated juvenile delinquency with violence and sex in comics. Parents navigating the postwar era were happy to indulge his theories. But not all artists wanted to sanitize their work. And what would art be without rebellion?

Soon the counter cultural “Underground Comix” movement was born. It involved the publication of small press comics filled with rude or satirical art. Artworks based on underground comix, stylized cartoons, and the burgeoning punk scene poked fun at conventional life. Young artist Art Spiegelman was inspired by the skepticism of politics, media, and society presented in works born out of the underground comix movement. While attending college, Spiegelman met Woody Gelman, art director of The Topps Company. Gelman invited Spiegelman to join the company as a freelance illustrator. He joined the team that developed Wacky Packages, a series of collectible trading cards that parodied commercial products like Ratz Crackers and Cracked Animals. Both of these were pulled when the company received cease-and-desist letters from the manufacturers of the products being spoofed, but that did not stop The Topps Company or Spiegelman from continuing to push the envelope.

In the early 1980s, The Topps Company decided to parody the Cabbage Patch Kids dolls with a series of collecting cards. The project was spearheaded by Spiegelman, cartoonist Mark Newgarden, and artist John Pound. The first Garbage Pail Kids set was released in June 1985 and sold for 25 cents per pack. Garbage Pail Kids looked remarkedly like Cabbage Patch Kids, but instead of encouraging nurture play and cuddling, these characters had rebellious attitudes and shock value. Kids intrigued by the gross-out humor and detailed illustrations could not get enough of them. Many parents and educators argued that the characters were vile—some administrators went so far as to ban them from school grounds.

Between 1985 and 1988, Topps released 15 series of Garbage Pail Kids. In 1988, Topps decided not to release any additional sets as the possibilities seemed exhausted, but in 2003, Garbage Pail Kids made a comeback. Garbage Pail Kids proved a pop-culture phenomenon. The chase for artist sketch cards, coupons, and parallels kept the brand fresh. Many collectors focused on a single character from the series, while others enjoyed set collecting. I personally like to look for any card with a puppy on it. Ancient Annie (sometimes referred to as Wrinkled Rita), for example, is adorned in a tropical print dress and holding the leash of a miniature poodle. It’s not a kind portrayal of aging, but that lends to engaging social commentary.

Topps banked on the success of Garbage Pail Kids with future projects like Gross Bears & Big Bad Buttons, a button collection set by artist Tom Bunk. Gross Bears mocked the popular and super sweet Care Bears originally created by artist Elena Kucharik. Instead of charming names like Cheer Bear and Funshine Bear, Gross Bears included Punk Bear, Melted Bear, and Trash Bear, among others. Barf Bear, the one that I can’t look at without feeling ill, had the tagline “Ready for Lunch?” The Gross Bears line did not enjoy the same success as Garbage Pail Kids and was cancelled until 2016, when the Gross Bears Big Bad Stickers were released.

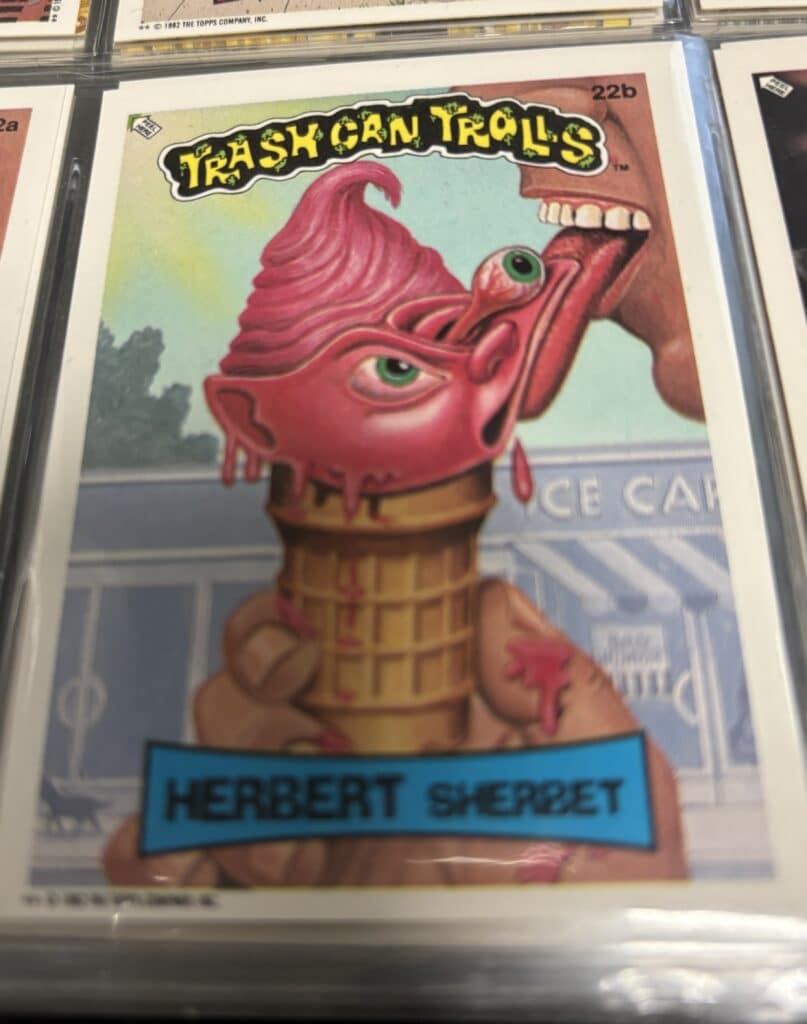

Topps also published Trashcan Trolls, a series of trading cards that parodied the Norfin Trolls fad in 1992. In the 1980s, marketing executive Eva Stark imported Thomas Dam’s troll dolls and rebranded them as Norfin Trolls. The troll dolls had sprigs of colorful hair, big eyes like those from a Margaret Keene painting, potbellies, and a tag marked “Adopt a Norfin.” Like Cabbage Patch Kids, Norfin Trolls were not conventionally cute, but they pulled at the heartstrings of Americans. Trash Can Trolls took the unconventional even farther with edgy and dark illustrations led by art director and editor Mark Newgarden and artists like John Pound, Tom Bunk, Drew Friedman, Irene Rofheart, and Patrick Pigott, among others. The cards came six to a package and had the tagline “totally trashy troll stickers.” Character had names like Barfin’ Barb, Herbert Sherbert, and Dustin’ Justin. The line seemed like a continuation of the bathroom humor and depictions of dirty things that started with Wacky Packages.

While some people consider these cards offensive and risqué (and I would agree that some of them are), they reflect a style of art and humor that has resonated within American popular culture for decades. Many of these cards still circulate as collectibles and several of the artists have gained a certain level of prominence among mainstream culture—not that they care.