On November 10, 2022, Masters of the Universe took their place of honor in the National Toy Hall of Fame. This is not the first time He-Man, Skeletor, and Castle Grayskull made recent headlines. Mattel Creations just launched a Masters of the Universe Origins He-Man 40th Anniversary Pack and fans who attended the San Diego Comic Con posted the grandiose Eternia play set to social media. Just this past July, Masters of the Universe: Revelation, developed by Kevin Smith, began streaming on Netflix. I championed for Masters of the Universe to get into the NTHOF, yet I did have one reservation. Do the images of He-Man impact male body image? Is He-Man the equivalent of Barbie whose voluptuous body and tiny waist has generated criticism since her inception in 1959?

The story of Masters of the Universe begins in 1979 when Ray Wagner of Mattel formed a Male Action Team to explore creation of the company’s next big action figure line. Until that point, Mattel’s action figures had been limited to Big Jim, a brawny sports hero, and a product that received a ho-hum response from kids at best. The company recognized that it needed to compete with the movie-fueled success of Kenner’s Star Wars action figures.

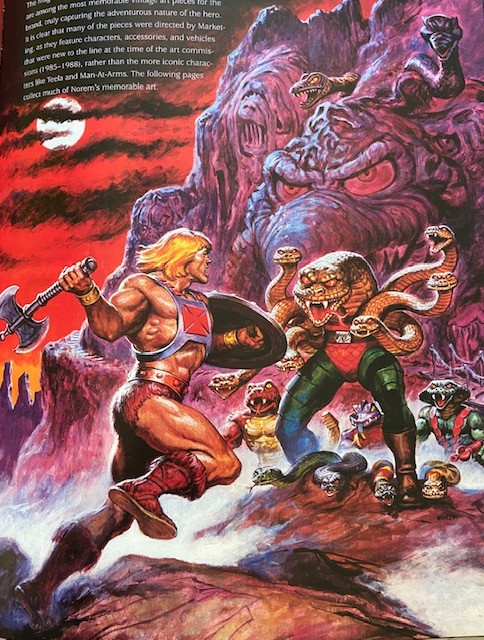

Roger Sweet, a member of the team, found inspiration in Charles Atlas (“the world’s most perfectly developed man”) and Frank Frazetta (painter of “The Destroyer”) when he decided to add modeling clay to bulk up Big Jim. Sweet wanted his action figure to make all other action figures look like wimps. If He-Man was scaled up to 6’1”, he would have weighed 720 lbs. (all of it vascular, sculpted muscles). In turn, Mattel illustrator Mark Taylor developed the proposed aesthetics for the action figure and, voila, He-Man was born. Instantly distinctive among competing toys, He-Man was super-ripped, scantly clothed, larger-than-life, and possessed brute force unlike any other action figure.

In my limited search, I was unable to find much criticism from the 1980s of He-Man and his friends and foes (all the males in the series had the same chiseled abs). There are academic studies of action figures and the male body. In “Evolving Ideals of Male Body Image as Seen Through Action Toys,” Harrison G. Pope, Jr., Roberto Olivardia, Amanda Gruber, and John Borowiecki measured the waist, chest, and bicep circumference of selected action figures and scaled these measurements using classical allometry. In comparing different versions of G.I. Joe, they found that the earliest figures had no visible abdominal muscles, but the modern figures showed distinct serratus muscles. The mid-1990s version, G.I. Joe Extreme, featured the equivalent of a 55” chest and a 27” bicep. A 1998 Batman had a 57.2” chest and 28.8” biceps and Wolverine had a 62” chest and 32” biceps. One could argue that Batman and Wolverine are superheroes and are not fully human. And while the advent of steroids and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s appearance in the 1977 film Pumping Iron, inspired some to bulk up, G.I. Joe Extreme was literally larger than life.

Contemporary scholarship suggests that these action figures do impact male body image. Dr. Raymond Lemberg, a clinical psychologist with a focus on male eating disorders, believed “the media has become more of an equal opportunity discriminator. Men’s bodies are not good enough anymore.” Action figures and the messages associated with these toys suggested more muscles mean more power. When considering the build of male action figures, Dr. Lemberg noted “only one to two percent of males actually have that body type. We’re representing men in a way that is unnatural.” Research suggested that children will resort to unnatural means to obtain a certain physique. In a 2012 study published in Pediatrics journal, the authors warned that “38 percent of middle-and high-schoolers surveyed were using protein powders and supplements to bulk up.” Some of these children also admitted to taking steroids.

When I casually asked my husband and a few of his friends if, as children, they aspired to have bodies like those of the characters from Masters of the Universe, I got a resounding “no way” and “it was just fun to play with them.” They also thought I threatened to “take the fun” out of He-Man and Skeletor by even discussing body image. Let’s not forget that this generation also grew-up listening to bands like Skid Row, Motley Crue, and Twisted Sister whose members were predominately white with long, permed hair, and long, slender legs clad in the tightest of pants. Anyhow, unattainable body images have been portrayed since Doryphoros of Ancient Greece.

All of this led me to the same thought I had about Barbie—despite the piling on by cultural critics and observers, when I look at these action figures, I see opportunities for creative play. Toys represent just a fraction of the ideas kids receive about body image. Frankly, I’m more concerned with educating my kids on the privilege implied by mass fitness, the health at every size movement, the dangers of misogyny, and the power of confidence. Mattel’s main-man, after-all, regularly asserted, “I have the power.” And self-esteem, in itself, is reason to celebrate the induction of Masters of the Universe into the National Toy Hall of Fame.