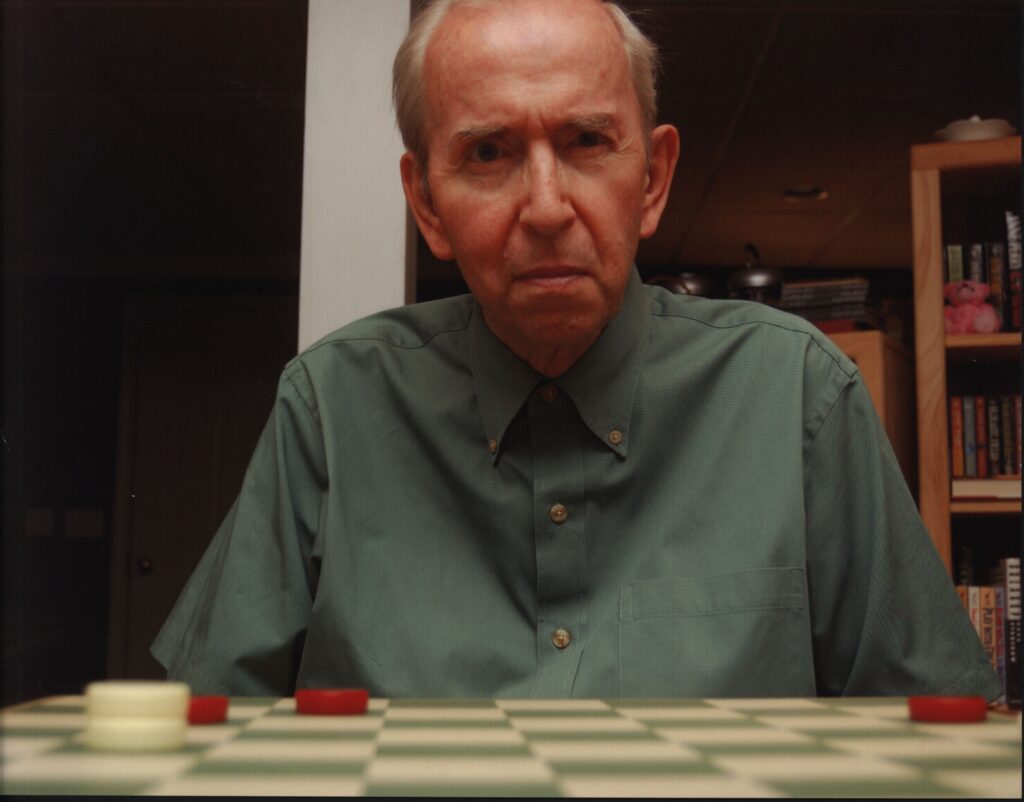

How to Win at Checkers, How to Beat Grandad at Checkers, Play Winning Checkers. These are the titles of just a few of the books from Alfred C. Darrow’s checkers library, which recently found a new home at The Strong Museum. The literature covers every aspect of playing a winning game, even How to Lose at Checkers, as it turned out. In my survey of Mr. Darrow’s vast collection, I discovered that I knew nothing about how to win—or lose—at checkers. Simply put, a player loses at checkers if they can’t make a move on their turn. You may find yourself in this situation after making a wrong move or falling for an opponent’s trap. Breaking any of the rules of checkers may cause you to have to forfeit the game.

If you are like me and many of my colleagues at The Strong, you probably haven’t thought about the rules of checkers since childhood. In the early days of my checkers studies, my team’s collective world view shifted upon learning that if you are in the position to jump an opponent’s piece, you are required to jump the piece. This fundamental aspect of the game had never been enforced by parents, teachers, or fellow children. Many historic school yard matchups were subject to the players’ invented, and arguable, rules. The games were after all just for fun, not to be taken too seriously. But for tournament checkers players, the rules are set and are the final authority.

According to the 24 “Standard Laws in the Game of Draughts,” listed in Anderson’s second edition of The Scottish Draught Player, a player can lose at checkers by taking too long to make a move, touching the wrong piece at the wrong time, moving a piece in the wrong direction, or even, as I was delighted to discover, doing “anything which may tend to either annoy or distract the attention of the player.” Yes, that’s right, annoying your opponent is against the rules of checkers. This includes, but is not limited to, “pointing or hovering over the board,” and “unnecessarily delaying to move a piece touched.” (Could somebody please inform my gaming group of this rule?)

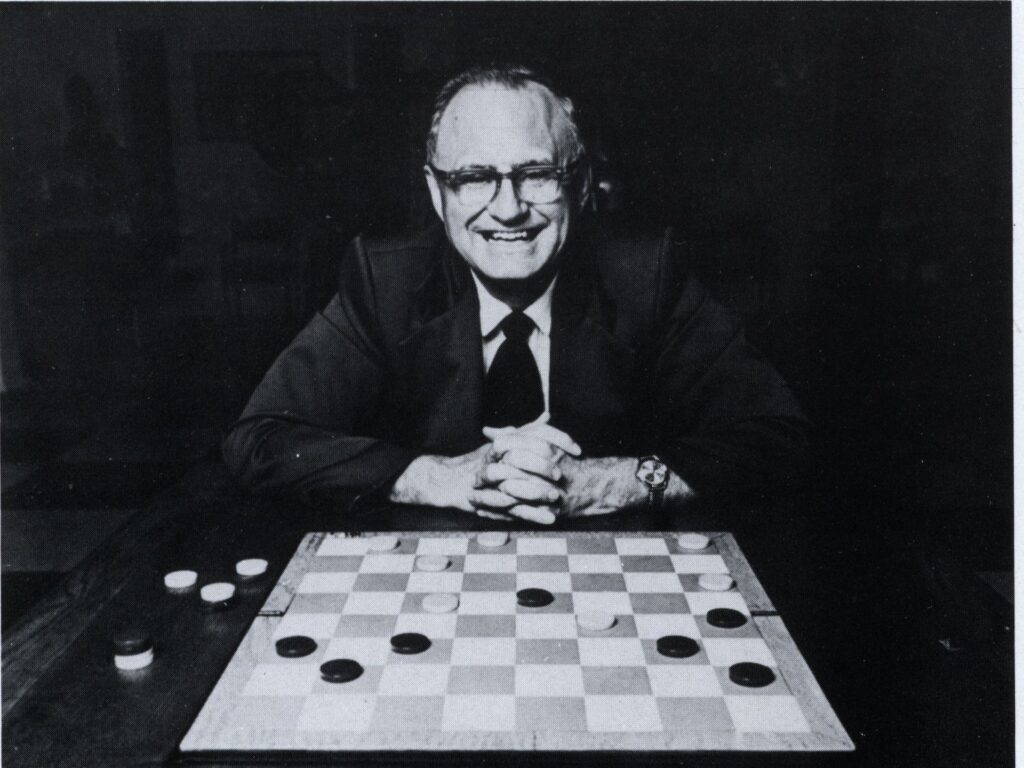

Now that I’ve straightened out checkers rules for you, let me tell you about one of the foremost checkers players of the 20th century, Marion Tinsley. Tinsley was so good at checkers that he is reported to have only lost seven times during his decades-long career. He gained a reputation as being unbeatable, and other checkers players aspired to a drawn game against him. For Tinsley, however, winning all the time became a bit boring. He even took a 12-year hiatus from playing at one point due to lack of competition.

In 1990, an up-and-coming new player entered the competitive checkers world: Chinook, a computer program developed at the University of Alberta. Chinook was programmed to play for the win, seeking out interesting variations backed by algorithms and a database of grandmasters’ opening moves, end-game positions, and known losing positions. In comparison with human players who tended to play cautiously, especially against Tinsley, the program was the greater risk-taker. In 1992, Chinook played Tinsley in a 40-game match for the World Checkers Championship and lost

Through its games with Tinsley, other human opponents, and copies of itself, Chinook continued to learn how each position would play out to a win, lose, or draw. Chinook and its developers used this experience to finally solve checkers—“solved” meaning that they could correctly predict the outcome of every possible move, assuming both players play perfectly. With that in consideration, perhaps it is now time to find an opponent and start a game of checkers.

By: Laura Boland, Processing Archivist at The Strong National Museum of Play