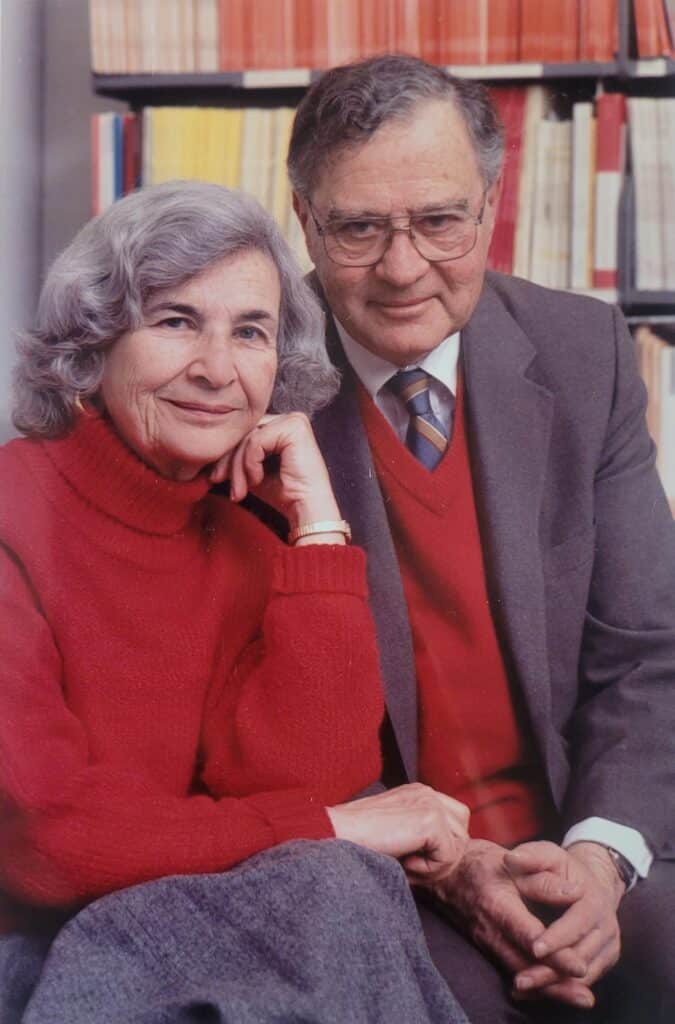

What impact do adults—and the stories, movies, television shows, and games they create—have on children’s imaginative play and development? For decades, researchers explored this question and arrived at a variety of conclusions. But few play scholars of late 20th and early 21st centuries proved more influential on this research than psychologists Dorothy G. (1927–2016) and Jerome L. Singer (1924–2019). Having grown up in the years before television when radio captured children’s imaginations, the Singers did not see television and new media as inherently negative. But as they noted in their 2005 book Imagination and Play in the Electronic Age, they worried that children growing up in a culture awash in television, video games, and later the internet were in danger of being left “adrift in cyberspace.” As they observed in their research, children who watched a lot of television (three or more hours per day) weren’t using their imaginations in their play as much as those who watched less (one hour or less per day). Similarly, they asserted that, in their pretend play, children increasingly acted out stories and characters predetermined by the media they consumed rather than formed from their own imaginations. To help address these concerns, the Singers believed that adults should create better television shows to help enhance children’s imaginative play and that caregivers and educators had a special role to play by guiding children through what some deemed a vast wasteland of media and television programming.

In 2021, the Singer family donated to The Strong a collection of Dorothy and Jerome’s books and professional papers that help document the couple’s significant work as play scholars, with an emphasis on their roles as codirectors of the Yale University Family Television Research and Consultation Center. A deep dive into this collection illustrates (among other things) that through their work at the Center the Singers sought to help shape children’s television through their own research on kids and adults; consulting with television producers and evaluating their programming; and advising parents, educators, healthcare professionals, and policymakers on children and youth television usage.

The massive proliferation of television in American homes in the 1950s and 1960s spurred many media scholars to study its potential effects. As pioneers in an emerging scholarly field, the Singers wondered if the medium could help educate children and enhance their creativity. In 1974, the couple began studying the children’s public television program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968–2001), a show in which host Fred Rogers brought viewers into a fictional “neighborhood of make-believe” populated by puppets. This research suggested that television programs like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood could enhance children’s imaginative play. But the show was most effective if parents watched television with children to act as, what the Singers called, “intermediaries” or “translators.” Backed by these conclusions, the Singers founded the Yale University Family Television Research and Consultation Center in 1975. Over the next nearly four decades, the Singers published dozens of articles and books including, Television, Imagination, and Aggression: A Study of Preschoolers (1981), The House of Make-Believe: Children’s Play and the Developing Imagination (1990), and the edited Handbook of Children and the Media (2001 and 2012), which examined, at least in part, television’s potential role in children’s development.

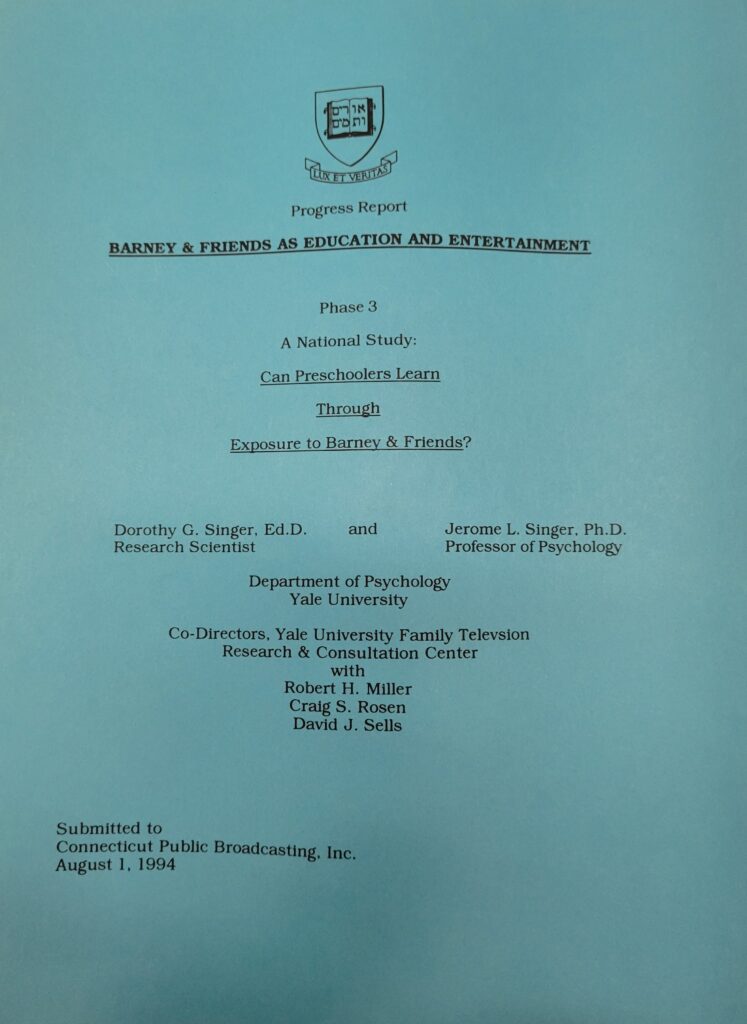

The Singer’s earliest research on specific children’s television programs started with Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, but it didn’t end there. The Center also studied shows such as Sesame Street (1969–present), Captain Kangaroo (1955–1984), and Degrassi Junior High (1987-1989). The couple had a particularly important influence on Barney & Friends, a program aimed at two- to five-year-old children and that centered on a costumed purple dinosaur named Barney. Launched in 1992 by Connecticut Public Television, the show remained on air until 2010. The Singers’ papers contain a bounty of materials related to the series, including research studies, content analyses, episode evaluation reports, research proposals, season synopses, scripts, and correspondence. All these materials paint a vivid picture of how much work went into producing a television series backed by research on the developmental benefits of watching Barney & Friends. But as the Singers contended, some of those benefits depended on how children watched.

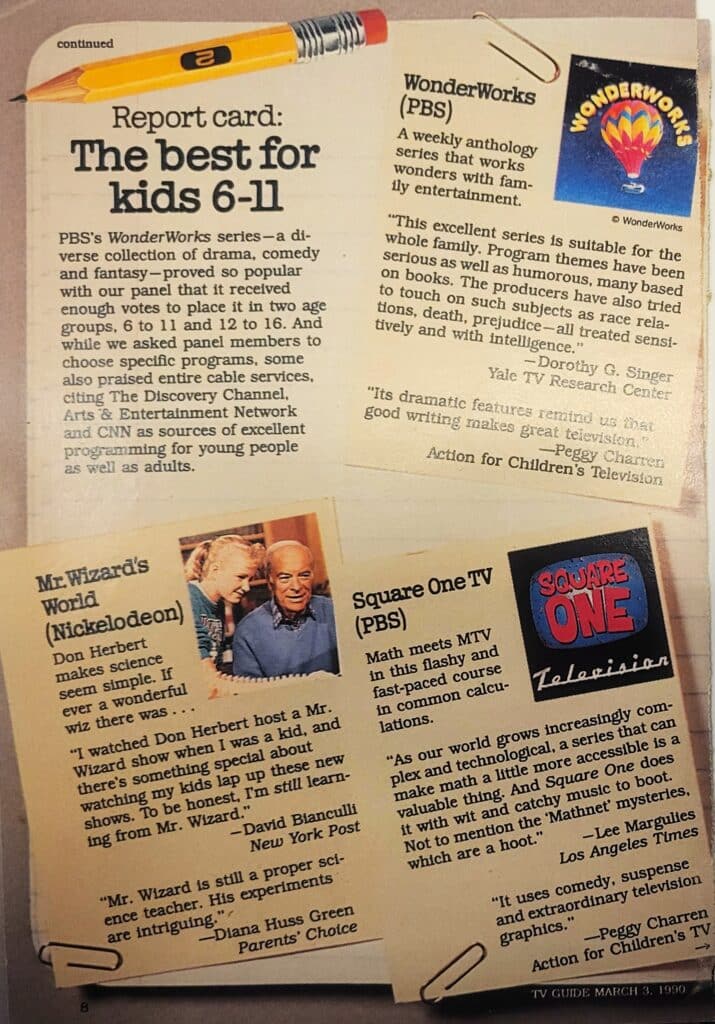

The Center focused part of its resources on working with caregivers, educators, and other adults on how to get those benefits from TV. Along with research partner Dianne M. Zuckerman, the Singers published Teaching TV: How to Use TV to Your Child’s Advantage (1981), Getting the Most Out of the TV (1981), and The Parent’s Guide: Use TV to Your Child’s Advantage (1990). These books aimed to assist caregivers and teachers with making sense of television and adopting strategies to harness it as an educational tool. In the early 1980s, Dorothy also contributed a monthly column on “Television and the Family” in the popular magazine TV Guide. In 1991, the Singers published Critical Viewers: A Partnership Between Schools and Television Professionals, which sparked the development of teacher and parent workshops to help train adults to make these television programs more interactive for the children that watched them. The next year, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting even commissioned the Center to prepare the report “A Role for Children’s Television in the Enhancement of Children’s Readiness to Learn” for the U.S. Congress. Taken together, these books, columns, and reports show the broad influence the Singers had on how adults viewed and understood children’s television.

On one level, this collection of the Singers’ books and professional papers provides us with a unique window into the relationship between play and children’s television in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. But on another level, the collection demonstrates the Singers’ life work and their sincere commitment to helping adults support children’s imaginative play and development. As the couple observed in The House of Make-Believe, when grownups think back to their childhood pretend play, those memories are “often associated with a special person who encouraged play, told fantastic stories, or modeled play by initiating games,” and who “above all showed a trusting, loving acceptance of children and their capacity for playfulness.”