We used to play a lot of Battleship when I’d babysit my little cousin after school. In the game, two players hide ships of various sizes on a grid then take turns announcing coordinates to attack. Since the players begin with no knowledge of their opponent’s formation, most early shots are launched into the open sea. But players mark each missed shot with a white peg, slowly deducing the positions of their targets. It’s only a matter of time until a player calls out a series of hits, prompting their opponent to exclaim the famous line: “You sank my battleship!” Playing with my cousin, I delighted in gimmicky strategies like hiding all of my pieces on the very edges of the grid or building complex daisy chains of ships resembling a Rush Hour puzzle more than a naval fleet. The devious grins I made at her confusion may not reflect well on my character. But all’s fair in love and fictional war.

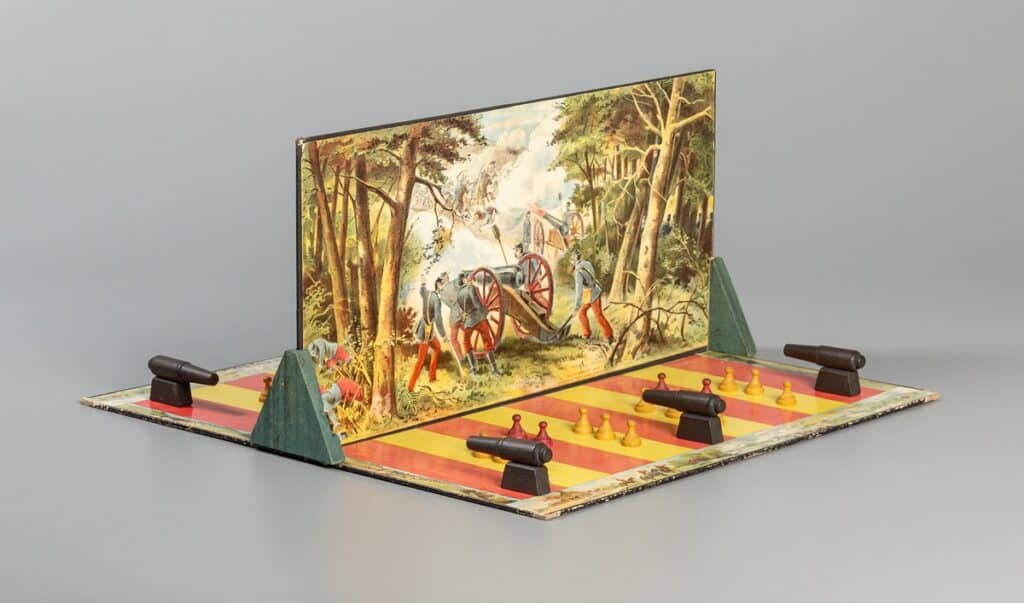

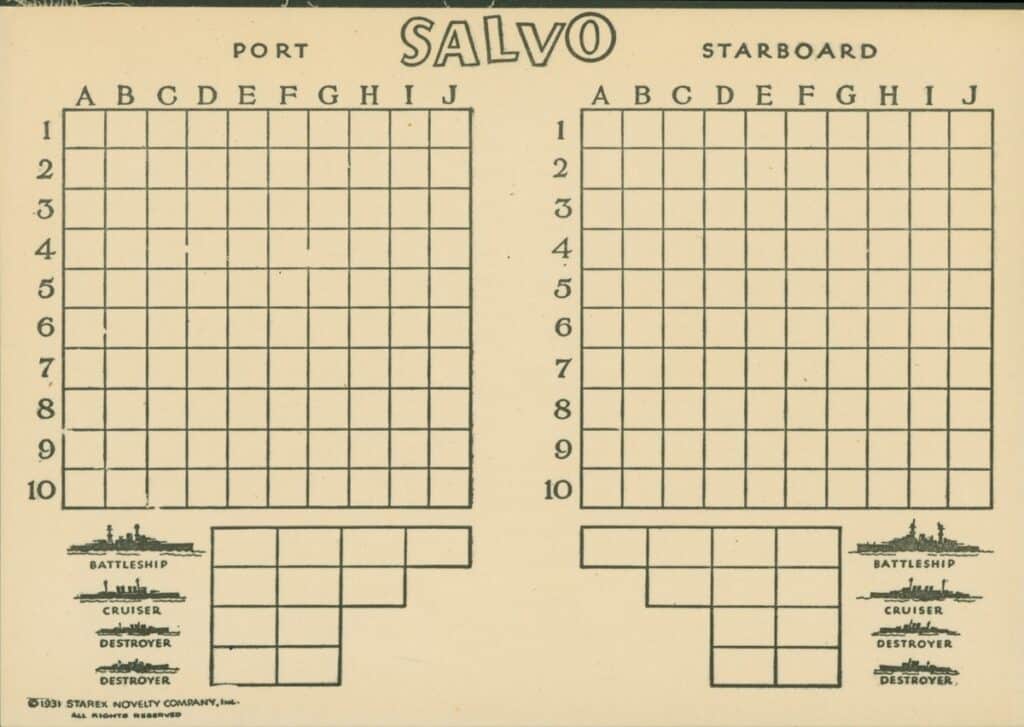

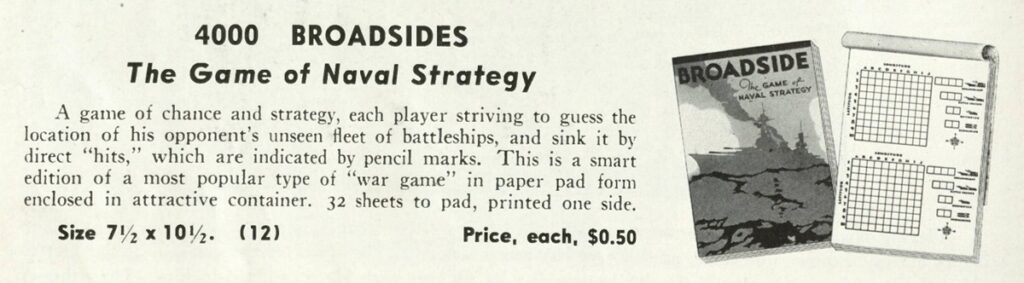

Battleship’s roots go back to the earliest manufactured war games. In 1890, the E. I. Horsman Company copyrighted its board game Basilinda, in which opponents arrange wooden pegs representing their army on either side of a cardboard screen. When the screen is removed, any soldier opposite an opponent’s cannon is removed from the board. During World War I, Russian officers reportedly played a game on a hand-drawn paper grid. In that game, players secretly plot the locations of their battalions or their ships and then must guess the position of opponents’ pieces by dropping bombs or firing shots. Starex Novelty Company’s 1931 game Salvo included printed grids to let players more easily plot ship locations. Milton Bradley manufactured a pencil and paper version in 1943 known as Broadsides: The Game of Naval Strategy, before publishing Battleship in 1967.

Battleship plays almost the same as the earlier pencil and paper games, except it uses plastic pegs and ships. A clever fold-up lid serves as the grid on which a player fires and marks shots while simultaneously blocking the view of the opponent’s ship positions. Milton Bradley advertised Battleship during the Saturday morning cartoon lineup that dominated many children’s television viewing in the late 1960s, as well as during prime-time programming. The original box design reflected the stereotypical gender roles of the day, depicting a father and son playing the game while a mother and daughter happily wash and dry the dishes in the background.

Since its debut more than 50 years ago, Milton Bradley’s Battleship game has sold more than 100 million copies. These include updated electronic “talking” versions and versions including additional rules that make the game more strategic. Some versions recall 1931’s Salvo, in which players could fire multiple shots at a time depending on how many of their own ships they had remaining. Others make more drastic changes. In 2023’s Battleship Royale, the game expands into a six-player shoot-out. Some releases change the game’s setting. One version takes place in the Pirates of the Caribbean universe, while others adopt the stylings of the Star Wars series. The game translates well to the computer, since the number of possible combinations for arranging a player’s ships is finite and grid based. First computerized in the 1970s, Battleship has since received video game adaptations on both personal computers and home consoles.

Battleship’s simple and exciting core gameplay and frequent re-releases have kept the game culturally relevant. In 2012, Universal Pictures and Hasbro even collaborated on a movie named after the game. While the film was only very loosely based on the game, its existence is an indicator of the game’s enduring popularity and its prominent place in popular culture history. Now, after four times as a finalist, Battleship has made port at the National Toy Hall of Fame. Maybe my cousin and I can celebrate the occasion with a rematch.