It’s 2025. Are you reading this on your smartphone or computer? It’s apparent that modern society is attached to its digital devices. When it comes to memories and our social media accounts, we all experience the same cycle. We take a photo with our phone. The photo gets added to the Photos app, buried among thousands of previously snapped images. It’s new today, but within a week, this image will be buried by tens—possibly hundreds—of newer ones. We upload it to social media with captions describing our day or providing whatever context seems appropriate, and it gets added to the feed. The post briefly appears in someone else’s sightline. Maybe it gets a “like;” if you’re lucky, a share—and then it’s swiped away. A quick Google search reveals that the average Instagram user spends only eight seconds looking at a single post in their feed. Then what? How often do we go back and look at digital images from years ago? Storage runs out, the cloud doesn’t update, the phone breaks—and they’re gone.

By today’s standards, it can be argued that digital storage is paramount to historical preservation. Paper is fragile and vulnerable to deterioration. Objects can be misplaced. However, I believe there is something incomparable about the physical practice of remembering. Photo albums and scrapbooks become curated art pieces, designed to personally reflect what the author wishes to share in the most intimate setting: a physical space. Holding them in our hands or resting them on our laps, we experience a tactile connection. Handwritten notations become evidence of gesture and intention—a personal disclosure between the viewer and the author. These objects act as time capsules, allowing us—sometimes hundreds of years later—to intimately learn the truths and stories they preserve, which might otherwise be lost to time.

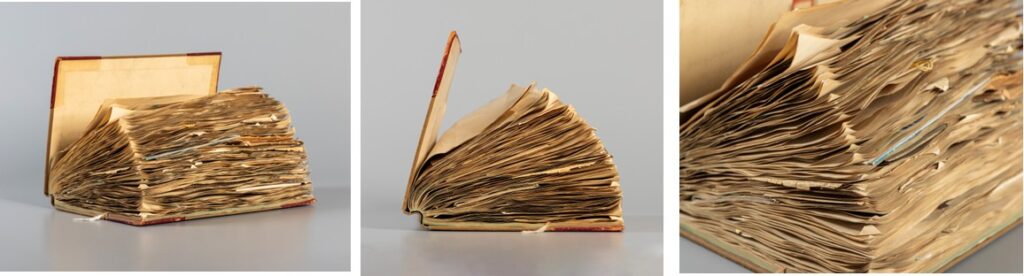

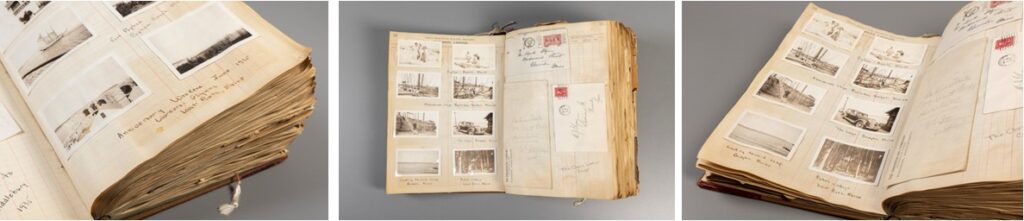

As a recently appointed collections specialist at The Strong, I’ve been fortunate to familiarize myself with our vast collection of photographs, albums, and scrapbooks. Recently, while browsing the stacks in one of our storage areas, I happened upon an old album quite literally bursting at the seams. This mammoth book sat on its back, pages arched like a discarded accordion. Its size alone made it difficult to ignore. Picking up the book, I felt its weight press against my wrists and forearms—a testament to the extensive collection of memories pasted between its pages.

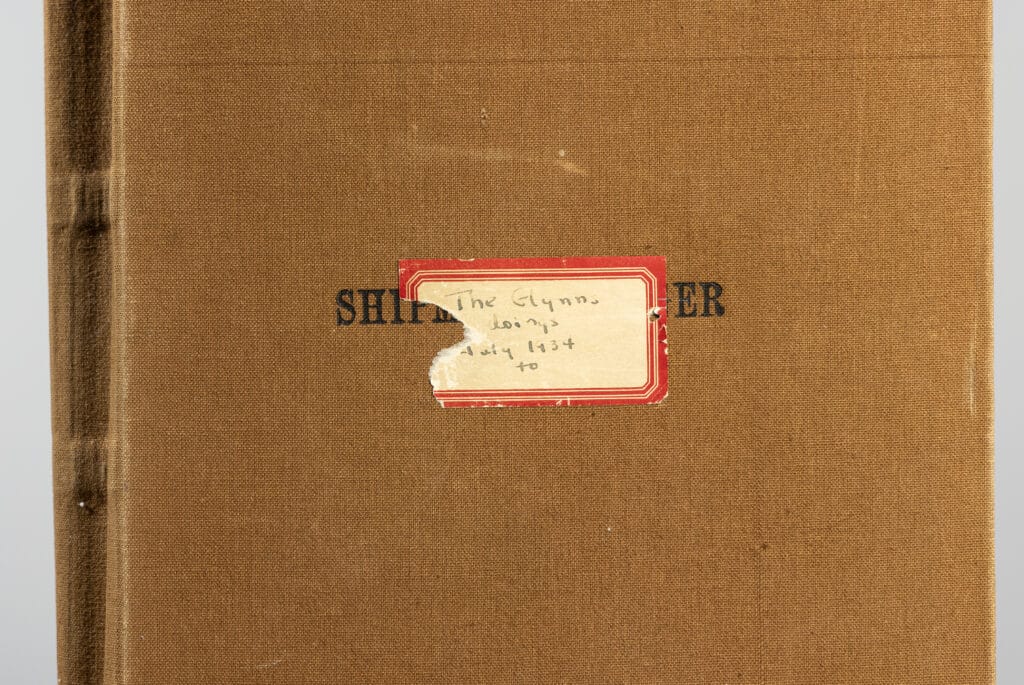

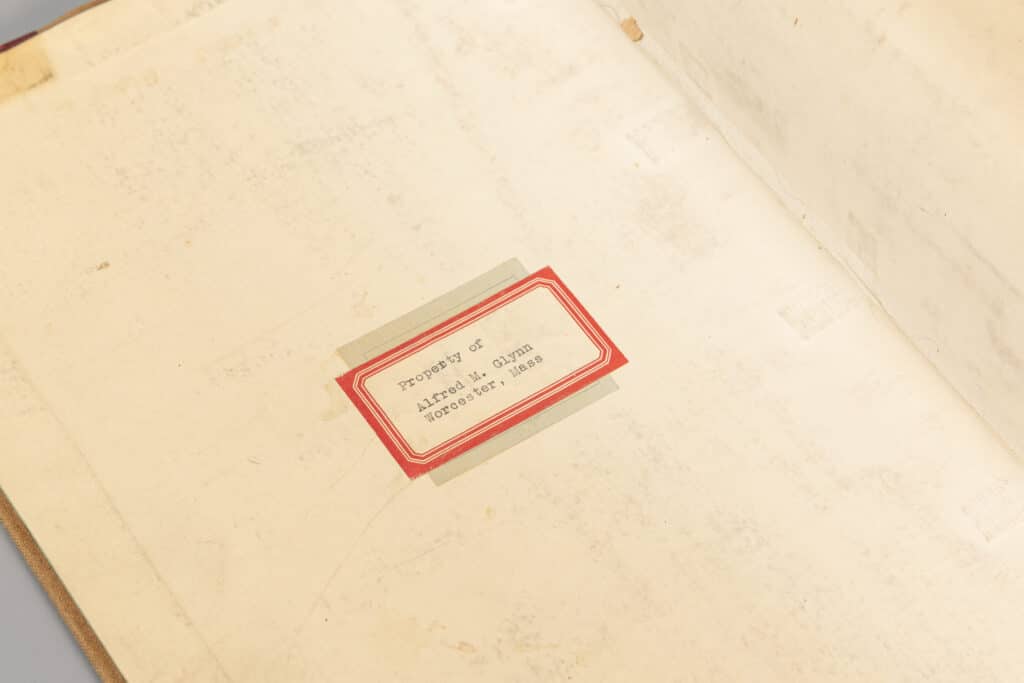

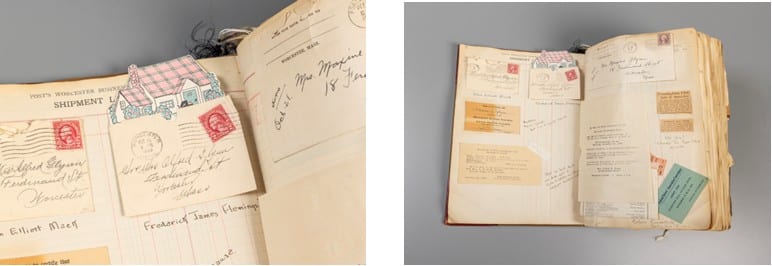

The most obvious place to begin was the cover. The face is wrapped in warm brown fabric with two large red leather corners. I decipher “Shipment Ledger” embossed across the center, though the title is partially obscured by a torn paper sticker. The inscription on the sticker reads, “The Glynns doings July 1934 to —.” The interior cover bears an additional label stating, “Property of Alfred M. Glynn, Worcester, Mass.”

I took this information on a brief side quest to our archive and found that the scrapbook was donated by the family in 1986. Along with the scrapbook were other loose photographs and memorabilia, which currently reside in our museum archive. I learned that Alfred Glynn—also referred to as “Al”—and Maxine Glynn were a married couple who moved to Worcester in the early 1930s. Al was a humble store manager, and Maxine was a part-time teacher and housewife. Though the book states it is the property of Alfred, it’s uncertain whether he alone maintained it.

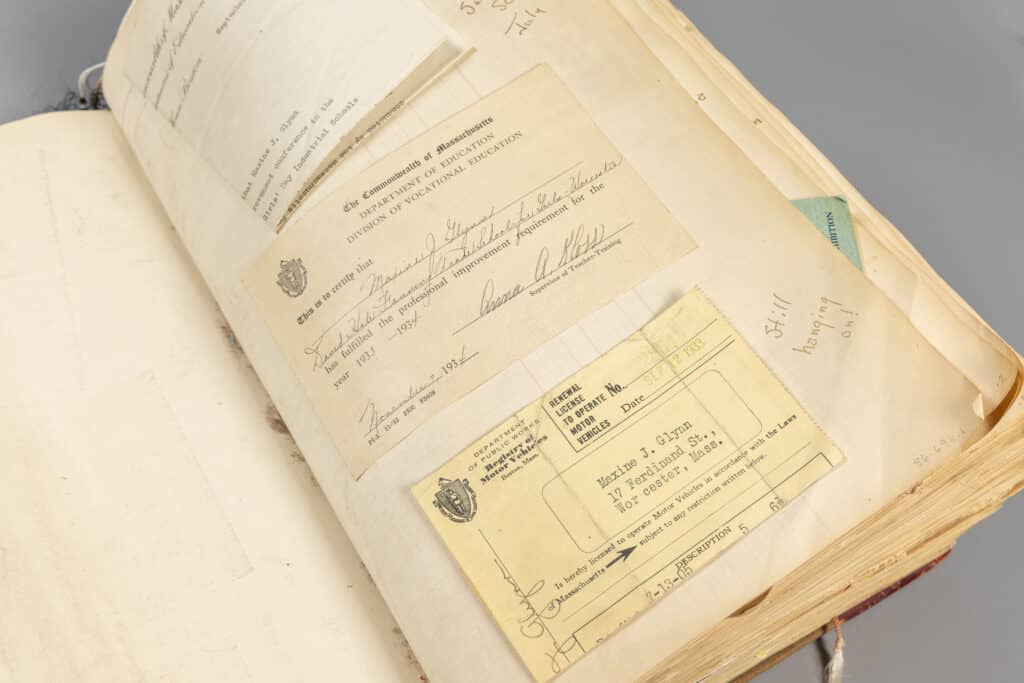

Page one is modest. The pages are an aged yellow hue, reflecting their near century of existence, but they have remained in relatively good condition. Since the Glynns chose a ledger over a traditional album, the backdrop for these memories includes faded blue and pink lines, along with printed header text. Each page is stamped with a number in the top right corner.

Adhered to page one are three pieces of folded paper: a summer school confirmation letter from July 1934, a vocational school certificate, and a paper driver’s license from 1933. Next to the license, a Glynn inscribed, “Still hanging on!”

Turning the page, the spread reveals a much more playful arrangement. Pasted directly onto the page are several envelopes. Inside one envelope is a colorful house illustration in pink and blue. At the bottom of the page is an invitation to the Worcester County Framingham Club’s “Hallowe’en Social,” dated October 27th, 1934.

On the right-hand page of the spread is a folded piece of paper, pasted on one side. I fold down the free half to reveal a request for used clothing articles—likely for a sale intended to raise money or provide clothing to the less fortunate. Two related newspaper articles are pasted nearby, accompanied by a handwritten comment: “Oh my! Thanks, Jo, for the gloves.” Below that is a handbill for a production of The Pursuit of Happiness, along with two pink ticket stubs dated November 19th, 1934.

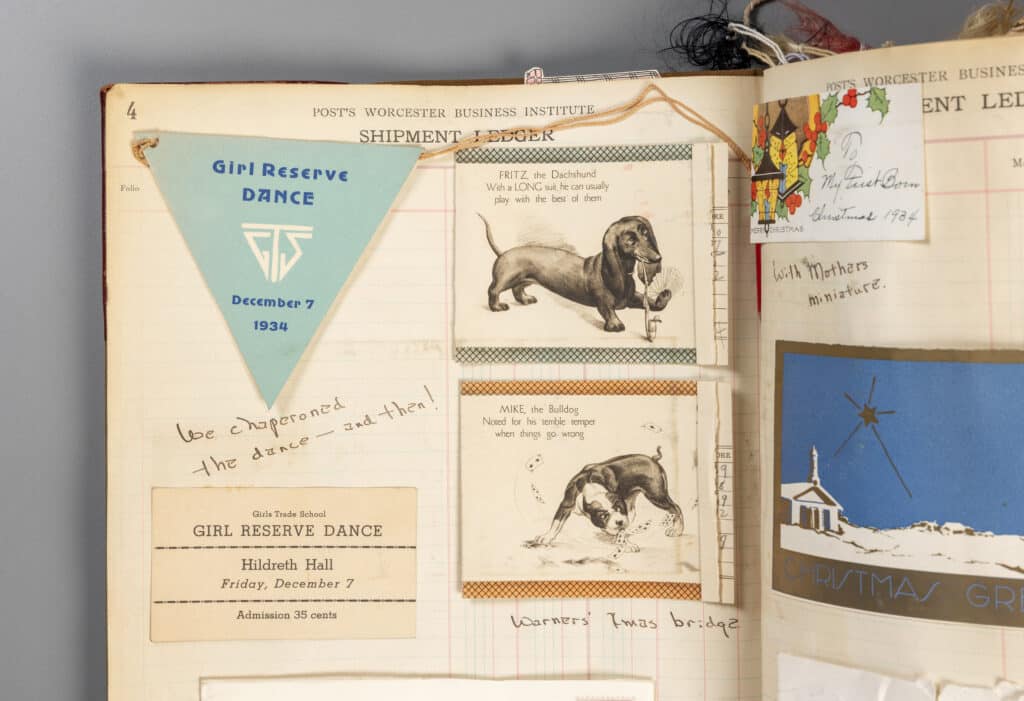

Pages four and five provide more notations and offer additional context for the time period. A memento from a “Girls Reserve Dance” appears alongside a ticket listing a 35-cent admission. The author notes, “We chaperoned the dance—and then!” next to two bridge “cards” from the noted “Warners’ Xmas Bridge.” These bridge cards served as official tally sheets. One card refers to “Fritz,” and the other to “Mike.” Based on what’s printed on the cards, it appears there were multiple tables with varying names. Each person was assigned to a table and a partner, and scores were then jotted down next to the appropriate line.

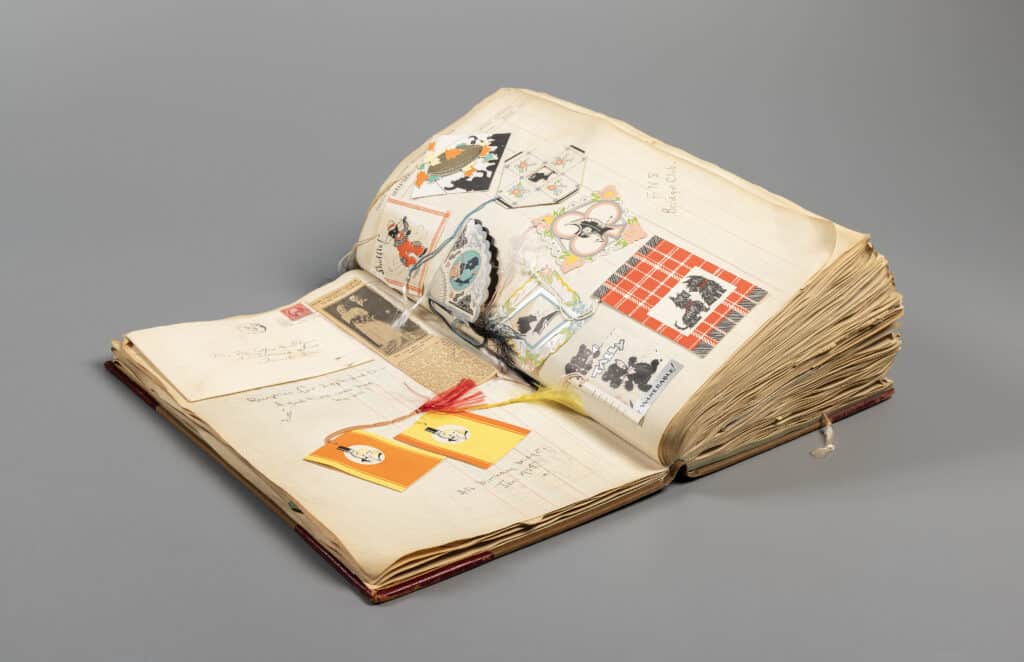

Flipping through to page seven, it becomes abundantly clear that the Glynns really enjoyed playing bridge. The page is decorated with various bridge scorecards in a variety of designs and colors, each claimed by different Glynn family members. Many feature colorful tassels with fraying edges.

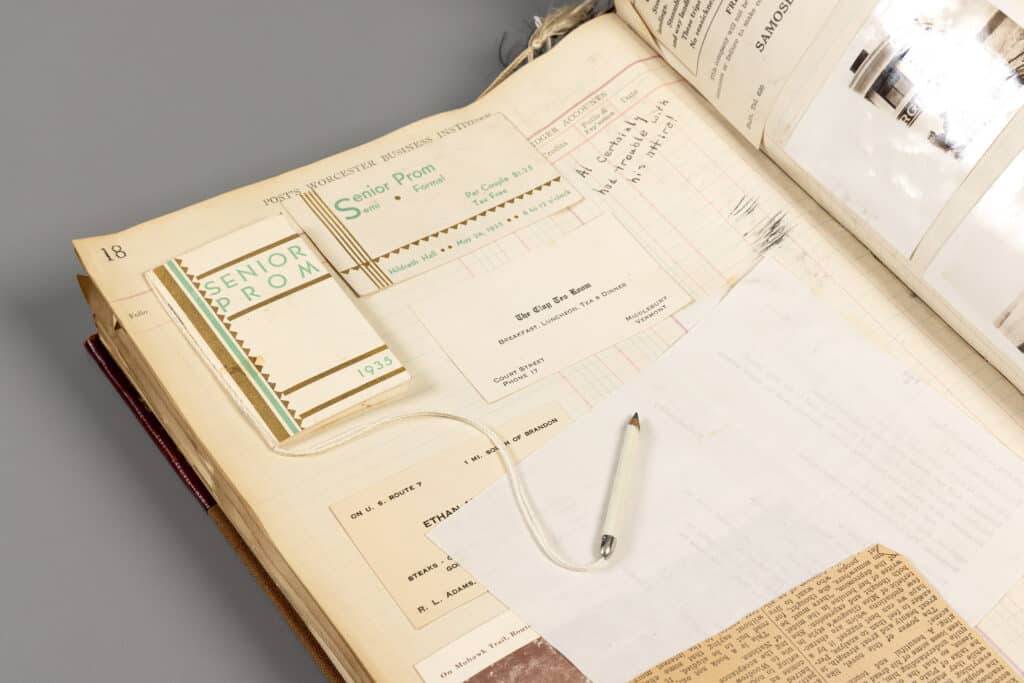

On page 18, I find a ticket and booklet for a senior prom semi-formal dance dated May 24th, 1935—marking the passage of a year across these 18 pages. The pasted booklet still has a pencil on a string attached, hanging freely from the binding. The author, who may be Maxine, jests, “Al certainly had trouble with his attire!” in a handwritten comment. Below, I see the first signs of travel for the Glynns: a postcard from Brandon, Vermont, a newspaper clipping of Lake Champlain, and a note reading, “Trips to Middlebury 1935.”

For the first time, photographs appear on page 19—seven small black-and-white prints, each about three and a half inches wide. A few images show three adults on a boat named Virginia, followed by landscape photographs of boats and islands. The author contextualizes the images at the bottom of the page: “Anniversary Weekend June 1935. Warners – Glynns. West Bath, Maine.”

These photographs continue on the following page in two-by-eight columns. More portraits appear by the water, alongside a large wooden ship and a car. The subjects in the portraits, along with the automobile, help create a more vivid visual context for the time period.

Though I could have spent the entirety of my day flipping through these pages, there was unfortunately more work to be done. For now, I’ll imagine it’s 1938. Alfred Glynn is sitting at his desk in Worcester, Massachusetts. In front of him is a large ledger—300 pages awaiting a long and meticulous chronology of Glynn family history. That object will become an artifact, preserved for 87 years and counting. That, my friends, is the glory of physical media